Exactly a hundred years ago, to the day – the 29th of April 1918, Tibetan government troops captured Chamdo. After a long and brutal siege the Chinese garrison finally surrendered. Following the liberation of what can be described as the capital of Eastern Tibet, the Tibetan army advanced all along the Kham front eventually freeing over half the territory of Eastern Tibet under Chinese subjugation. For over a thousand years since the Imperial period, such a major victory over Chinese forces had not taken place.

This historic event has been mentioned in some of my previous posts and essays. I want to discuss it again today in more detail not only because of the centennial but to remind Tibetans that far from excluding Kham and Amdo from the sphere of independent Tibet, as Middle Way apologists dishonestly insist, the government of old Tibet was even prepared to go to war (when it could) to assert its sovereign claims over the lost territories of Cholka-soom – on this occasion, quite successfully.

Background to the war

After the 13th Dalai Lama returned to Lhasa on January 1913 we know that he took immediate steps to modernize Tibet’s army. Tsarong Dasang Dadul who had commanded the Tibetan irregulars that defeated the Manchu garrison in Lhasa in 1912, was made commander-in-chief of the new army. Jampa Tendar who had headed the War Department and had organized the irregular Tibetan force in Lhasa was raised to cabinet rank as kalon lama. In addition he was appointed governor general of Eastern Tibet (domey chikyap), as the Chinese presence in Kham had become ever more threatening

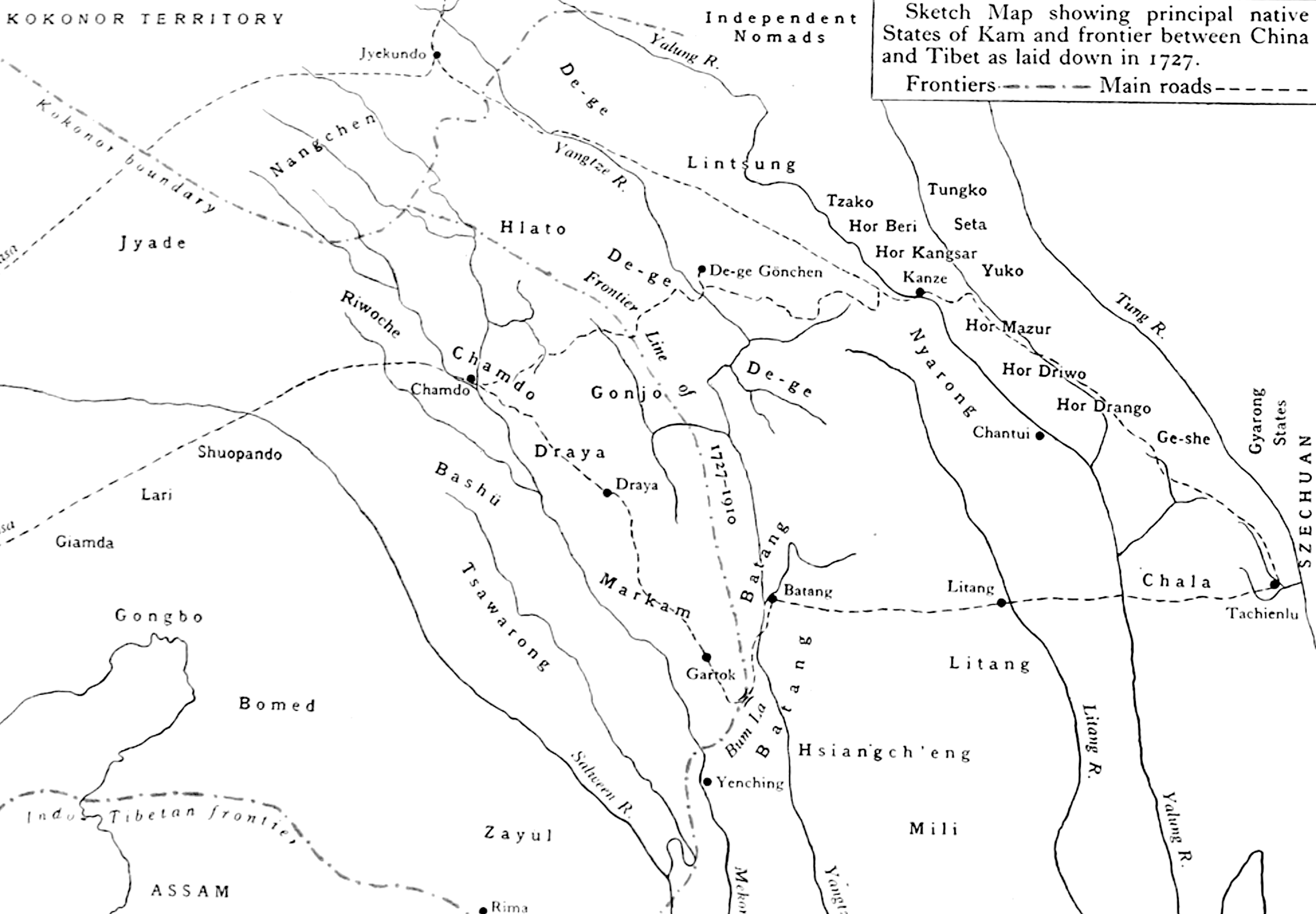

With the fall of the Manchu Dynasty and the death of Sichuan viceroy Zhao Erfeng, the Chinese had, for some time, lost much of their earlier control of Kham. But starting from 1912 Republican troops recaptured – with great bloodshed and destruction – Dhartsedo, Batang, Chatreng, Tawu, Chamdo Draya and Markham, as far West as Riwoche (Derge and Kanze had remained in Chinese hand). By 1914 the Chinese front line extended all along the Salween (Gyalmo Ngo-chu) valley.

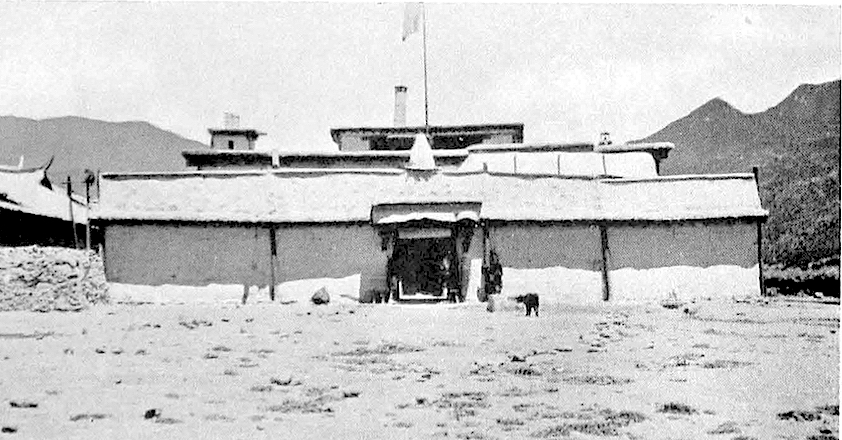

Tibetan forces held the Shopado and Lhorong districts. Kalon Lama Jampa Tendar’s headquarters was at Lho Dzong just west of the Gyalmo Ngo-chu River near the Shabye Zamba bridge. Initially his men were untrained ill-equipped levies but by 1917 he had managed to transform this into several regiments of well-trained troops armed with British Lee Metford rifles. These weapons had been acquired in a secret side-deal at the Simla Conference of 1914 whereby two valleys in the Tawang district were signed over to the British for their assurance of support for Tibet’s sovereignty (or “suzerainty” as they termed it when it didn’t suit them) and for the aforementioned arms sale. The British had made it impossible for Tibetans to purchase weapons from any other country. Tibetans had earlier tried and failed with Russia and Japan. Tibetans also had to pay in silver for every weapon or bullet purchased.

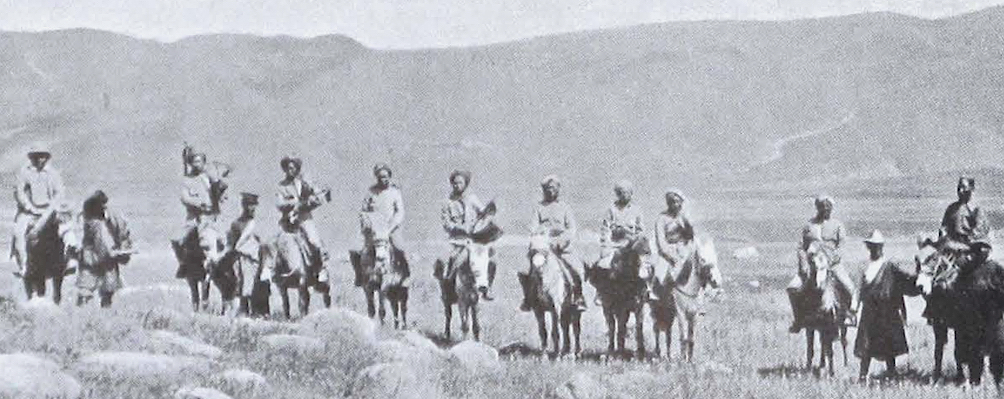

Jampa Tendar had under him eight generals (dapon): Phulungwa, Jingpa, Ragashar, Tethong, Khyungram,Tayling, Tsogo, Marlampa and Tana, all of whom had seen action in the earlier fighting against the Manchu occupation force in Central Tibet. I only have four old photographs of these dapons, two that I am not quite sure of. Any further information on these military leaders would be greatly appreciated. Photographs would be more than welcome.

How the war started

General P’eng Jih-sheng did not seem to have realized or appreciated the newfound strength of the Tibetan army. Quite foolishly he used the pretext of two Tibetan soldiers wandering across the Chinese side of the frontier, to launch a major attack on Tibetan headquarters. The Chinese advance came in three columns, from Riwoche on the North Road, Ngamda on the Main Road (gya-lam) and Drayab on the South Road. The following account of the initial Tibetan reaction was given to me by my uncle Sonam Tomjor the eldest son of Tethong Dapon. The Chinese attack came around the time of the Tibetan New Year (February 12th ) when Tibetan troops were celebrating and perhaps not as vigilant as they should have been. The Kalon Lama had come down with a bad flu/fever and was indisposed. Somehow the Tibetans managed to hold back the initial Chinese attack and in the next crucial few days, Jampa Tendar recovered sufficiently to launch the Tibetan counter-offensive.

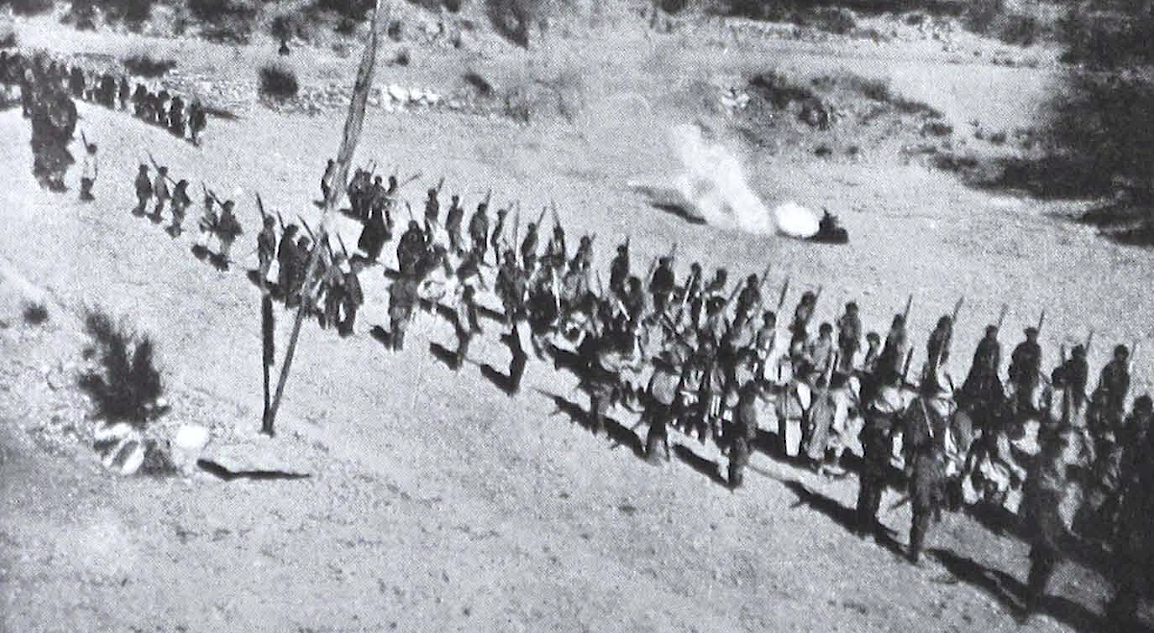

A force under Phulungwa and Tethong attacked the Chinese on the North Road taking Riwoche, Dapon Tsogo and Tayling confronted the Chinese column on the Main Road to Chamdo, and Khyungram and Tana (together with Khampa militia) advanced on the South Road pushing the Chinese back to Drayab. Shakabpa writes “After many months of fierce battles, Tibetan troops recaptured Rongpo Gyarapthang, Khyungpo Sertsa, Khyungpo Tengchen, Riwoche, Chaksam Kha, Thok Drugugon, Tsawa Pakshod, Lagon Nyenda, and Lamda.”

The Siege of Chamdo

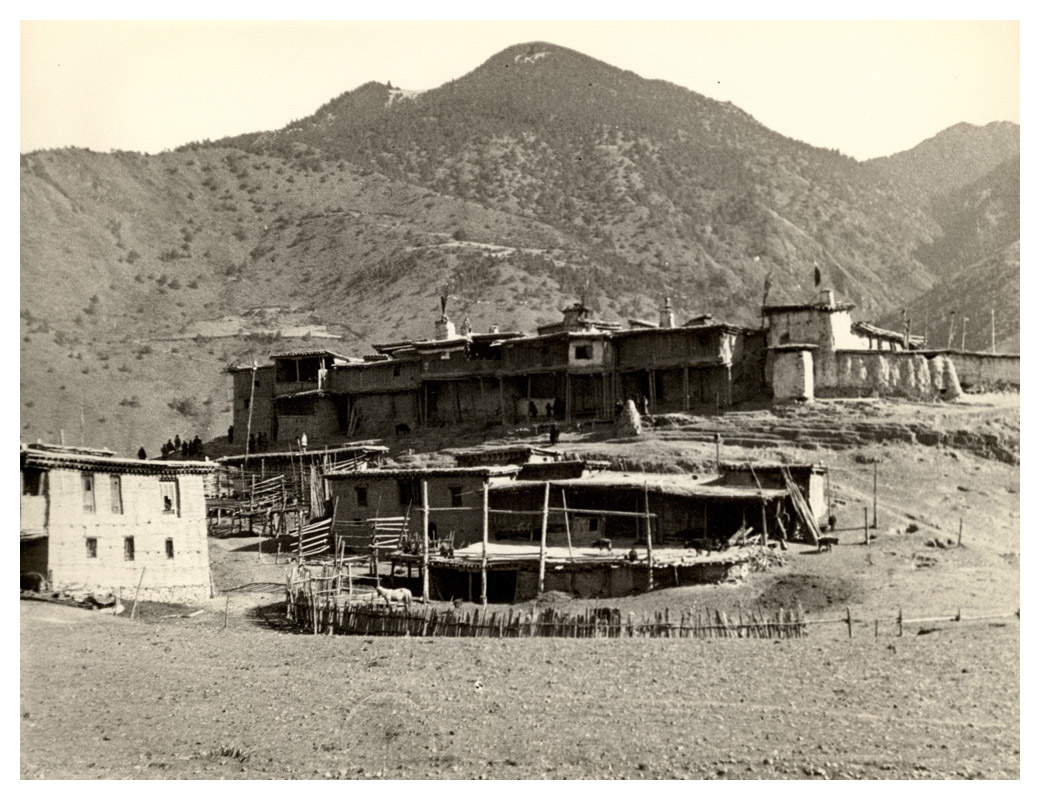

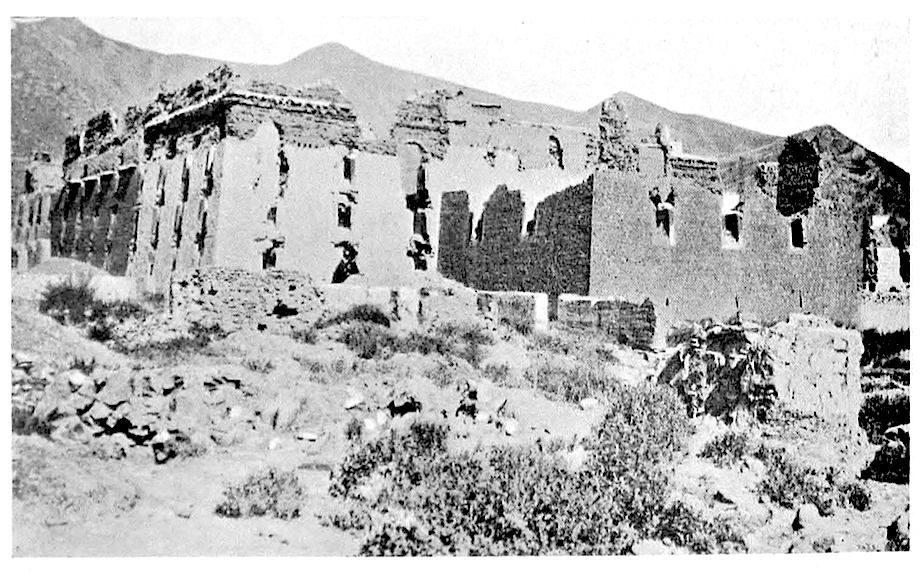

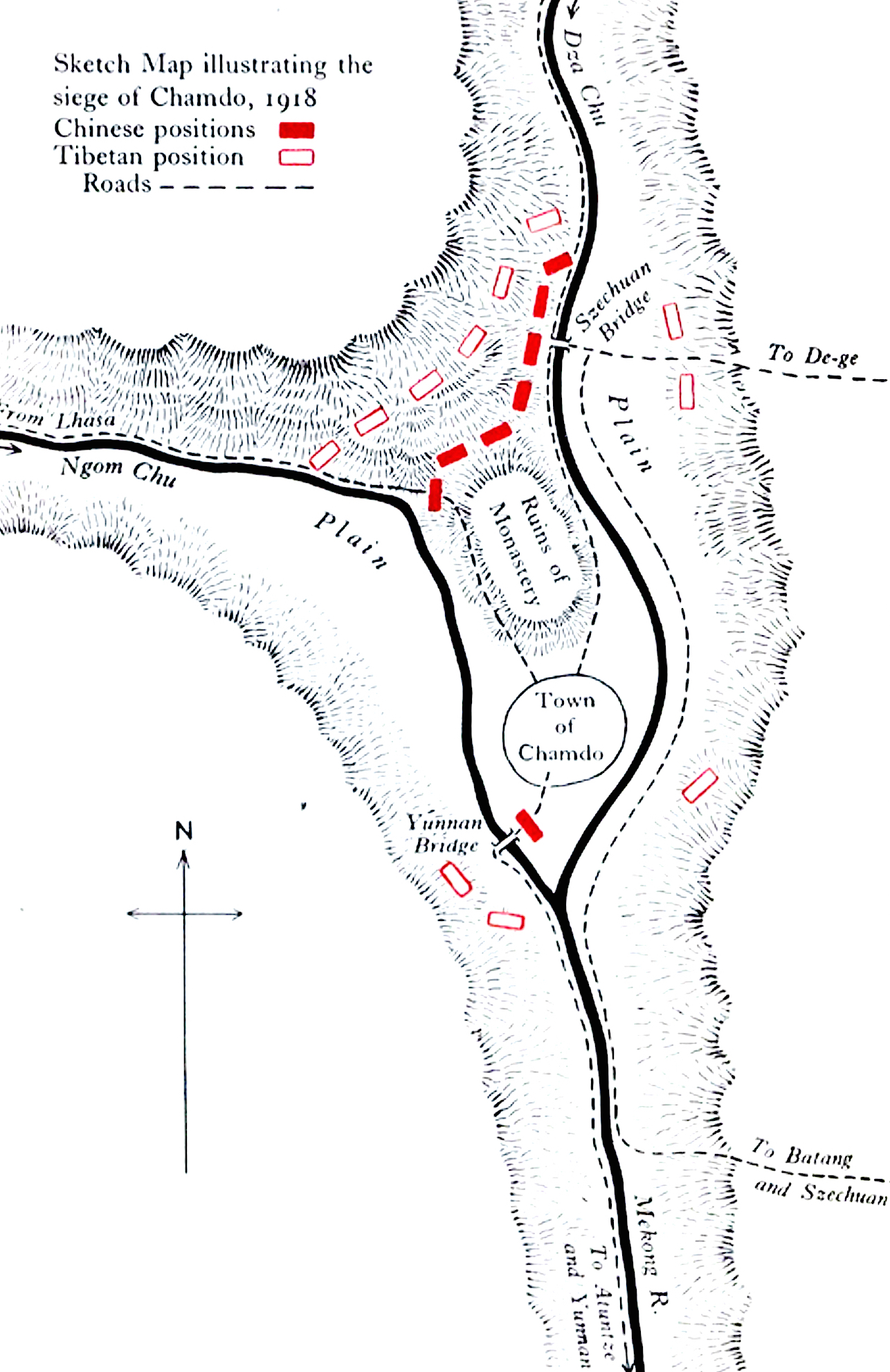

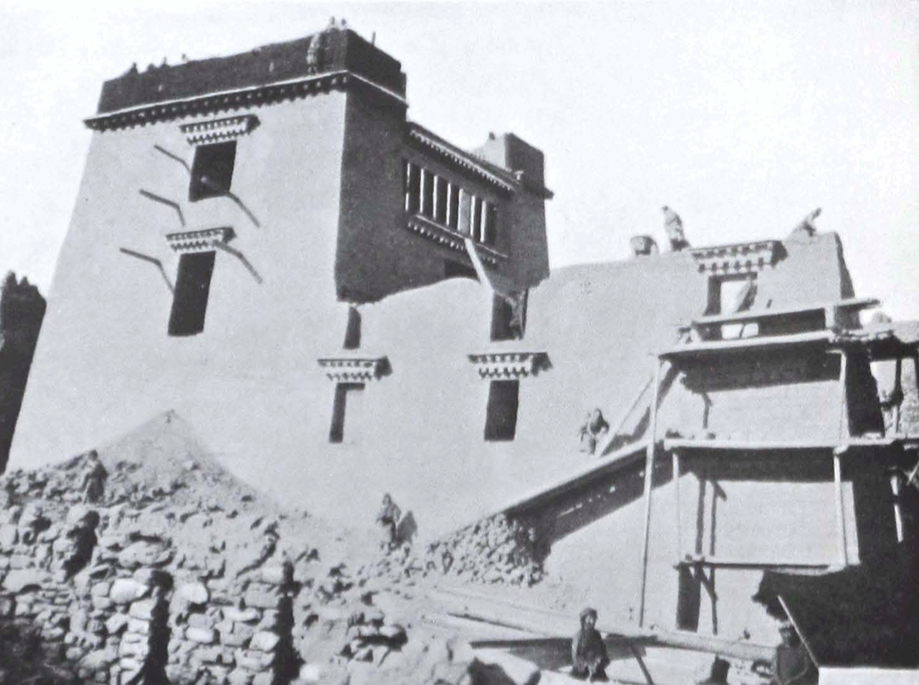

The defeated Chinese troops fleeing the Tibetan advance retreated to Chamdo. There they attempted to defend themselves in the ruins of Chamdo monastery (Chokhor Kelden Jampa Ling) destroyed by General P’eng Jih-sheng in 1912. The siege of Chamdo was a long and bitterly contested one. The Chinese high command rushed relief columns from Kanze, Dhartsedo and Bathang, but these were defeated by Tibetans before they got to Chamdo.

The Chinese defenders of Chamdo, over a thousand men, were gradually worn down by unceasing Tibetan rifle fire. Tibetan troops fought from behind stone breastworks (tib. dzingra) that were, every day, pushed closer and closer to the Chinese front lines. Finally the Tibetans managed to bring up captured cannons, manned by Chinese gunners the Tibetans had earlier taken prisoner. They now began firing point-black on the Chinese front lines. Over five hundred Chinese soldiers, almost half of the original garrison, were killed by the incessant bombardment and rifle-fire. Food shortage and disease also contributed to the grim Chinese death toll inside the besieged monastery.

General P’eng Jih-sheng now surrendered unconditionally and the victorious Tibetan army entered Chamdo town. As mentioned at the beginning of the post this happened exactly a hundred years ago to the day – April 29th 1918. The price of this great victory was a heavy one. Tibetan casualty figures were high and, in fact, three Tibetan generals: Dapon Phulungwa, Dapon Jingpa and Dapon Taling were killed in action. Khampa militiamen (tib. yul-mak) serving with Tibetan troops (tib. bhö-mak) also suffered heavy losses. One of the leaders of the Kham militia, Khenchung Dawa-la of Chamdo, was later given the title of Khenchen for his heroic service. He served under governor general Lhalu in 1948-49. Even when Ngabo surrendered the elderly Khenchen Dawa-la told radio-operator Robert Ford. “Tell the world we fought,” he whispered fiercely, “and that we’ll fight again.”

Shakabpa tells us that after the fall of Chamdo the Kalon Lama briefly rested his troops before resuming his advance into the rest of Eastern Tibet. The late K. Dhondup wrote that, “Tibetans in Markham, Draya, Sangen, Gonjo and Derge etc. where the suppression was on the increase could wait no longer and started rebelling against the invaders. Poorly equipped and disorganized, they suffered terrible losses. Before long, Kalon Lama Jampa Tendar (the governor general of Eastern Tibet) was able to assist them and liberate and recapture all these areas.”

The victorious Tibetan army was advancing on the ancient Tibetan frontier town of Dhartsedo, then the capital of the new Chinese province of Xikang (carved out of Eastern Tibet), when the Chinese appealed to the British for mediation. Chinese officials and the business community in Dhartsedo and Batang were “completely panic-stricken” and “lost their heads”, though Tibetan residents there were understandably celebrating.

Eric Teichman, of His Britannic Majesty’s Consular Service in Peking, was sent to Chamdo where after a number of talks with the Tibetan governor-general a treaty was finally signed at Rongbatsa. Tibetans gains in Riwoche, Dzachukha, Denkhok, Lhatoe, Chamdo, Drayab, Gonjo, Tsawarong, Markham, Derge and part of Kanze district were maintained, while Litang, Batang and Nyarong remained under Chinese control. Tibetans were confident they could have taken back Dhartsedo and other ethnic Tibetan areas under Chinese occupation. It was felt by Tibetan officials and the public at large, that the British had pressured the Lhasa government into signing the Treaty of Rongbatsa by threatening to cut off ammunition sales to Tibet if it did not do so.

Even if not as complete as the Tibetans would have liked it to be, the victory was undeniably a momentous one. It was clear proof that a trained Tibetan army was capable of defending its own frontier against Chinese aggression, and together with the victory of 1912, provided the self-assurance and sense of historical validation that Tibetans needed to establish in themselves the concept of an independent Tibet as an enduring reality and not merely as a declaration or a desired ideal.

Tibetans customarily refer to military events by the year in which they occurred. The British invasion is called the Wood-Dragon War (shing-drug mak). The expulsion of the Manchu forces in 1912 is called the Water-Mouse Chinese War (chu-chi gyamak). But Khampas probably felt that the 1918 victory was a turning point in their history for they speak of it grandiloquently as the “The New Epoch of the Earth-Horse” (kalpa sa-ta lo). It was not just a war. It was the liberation of their homeland (phayul).

–––––––

For further information I would recommend Shakabpa’s Advanced History, Vol II, pp. 251-324. (English translation Vol 2, pp. 789-844). Then there is Eric Teichman’s Travels of a Consular Officer in Eastern Tibet, which is sympathetic to Tibetans but provides the Chinese point of view as well. Readers requiring a brief but full summary of this period should read K. Dhondup’s The Water Bird and Other Years, pp. 54-56.

There is one reference you have missed; there is a fantastic description of Kalon Lama Jampa Tender and the events in Kham in a little-known book by Louse King, China in Turmoil, Studies in Personality, pp:190-208,(published in 1927). King describe Kalon Lama “like Sir Galahad, his heart was pure, and he was absolutely sure of himself”. Will send you a pdf of the chapter.

Guys, I need some reading about war and justice between China and Tibet. Can anyone recommend me some. Thanks

Reading Jamyang La’s articles opens up a whole history.

you are the foremost authority! The rock of Rangzen,

JN’s latest history lesson couldn’t have come at a better. It comes on the heals of a very disturbing news that the political ground has started shaking for the Tibetan cause.

The latest news from India that Modi’s nationalist government has pledged the supreme Chinese leader Xi to upend the Tibetan issue for good by agreeing to work for the Dalai Lama return to China (and Tibet). Also stunning is the possibility of Karmapa Lama’s return to China via America (where he is now).

The unexpected meeting between the Dalai Lama and the American ambassador in India is also puzzling because president Trump has not spoken a world about Tibet or the Dalai Lama since he took over the office (although the Dalai Lama has made some unfortunate comments of the American president who has not yet counter punched the Tibetan leader).

Could the apparent thawing of the Korean peninsula also shake the Himalayas and trigger thawing Central Asian freeze that would ultimately lead to a Dalai-Xi summit down the lane.

There is no doubt that India, under Modi’s Hindu nationalist hate the Communism and Xi’s unchecked move to control the greater central Asian and mass across the infamously legendary Silk Route – now being called “One Belt, One Road”which, not surprisingly, has failed to recruit India. If India were to continue its distance from China, Tibet is the only land mass capable of restoring the buffer it provided against Chinese onslaught for centuries.

Sikyong Sangays’s quirky decision to hold the 30th Tibet Task Force meeting suddenly has gained some traction to his recent assertion that Dharamsala-Beijing Dialogue could materialize in two or three years or it is dead after his term expires for good.

An amicable solution of the Tibet-China issue would definitely prove worthy of a Nobel Peace Price Sangay could be dreaming already.

Fully agree with L. Tsho’s succinct views. Much to think about and absorb.

As mentioned by Lelkyi Tsho, it is rather difficult for me to imagine that India would give up the one issue, that of Tibet, their one trump card so easily, with one visit to China by PM Modi. Nevertheless, India has always been playing her ace particularly submissively. As far as His Holiness’s return to Tibet, President Lobsang Sangay has made it abundantly clear he is going to fulfill the “Dream”. The interesting question is how? The United Front Works Department has never proved to be trustworthy in the least if he is relying on them for a dialogue. It is such a shame that we are in such short supply of heroes like Kalon Lama and burdened with an abundance unwitting conspirators in our midst.

Thankyou Jamyang Norbula for keeping Tibet’s Independence & Sovreignty RELEVANT especially NOW with your well documented history & journalism.

I can imagine how much you miss your Rangzen brother Prof. Elliot Sperling, when even those of us who have only read & heard of him feel this loss.

On the other hand beware of the Wolves in Reporter’s clothing these days- Sowing seeds of confusion.

Thank you Gen Jamyang lak for the research and sharing this with the worlds.

FREE TIBET

Wow, fighting in the ruins of a monastery? That reminds me of the lead up to the Sampa Lhundrup prayer to Guru Rinpoche, where before Guru Rinpoche is about to leave Tibet to subdue demons elsewhere in the Himalayan belt, the young king of Tibet pleads with him not to leave and describes the downfall/degeneration of Dharma in Tibet without the Guru’s allegiance. One of the specific degenerations was monasteries becoming fighting grounds and battle fields. It is an interesting connection IMO. https://www.lotsawahouse.org/tibetan-masters/tulku-zangpo-drakpa/leu-dunma-chapter-7