McMindfullness & Traditional Buddhism

JAMYANG NORBU

In a promotional talk for his insightful book Why Buddhism is True, evolutionary psychologist and mindfulness meditator Robert Wright made a statement that perplexed me: “And by the way, most Buddhists in Asia don’t meditate; it’s a kind of Western stereotype. They don’t meditate, but they do believe in deities.” [1] I have heard similar remarks from so-called “secular Buddhists”—that in traditional Buddhist societies, people just worshipped the Buddha in a devotional, supernatural way and did not practice meditation as modern Buddhists in the West do.

I cannot speak for traditional Buddhists in Sri Lanka or Southeast Asia, but as a Tibetan layman with some basic awareness of traditional Tibetan religious practices and customs, all I can say is that Wright isn’t just wrong here, but that he doesn’t seem to know what he’s talking about—at least on this specific point.

Meditation in Tibetan Visual Culture

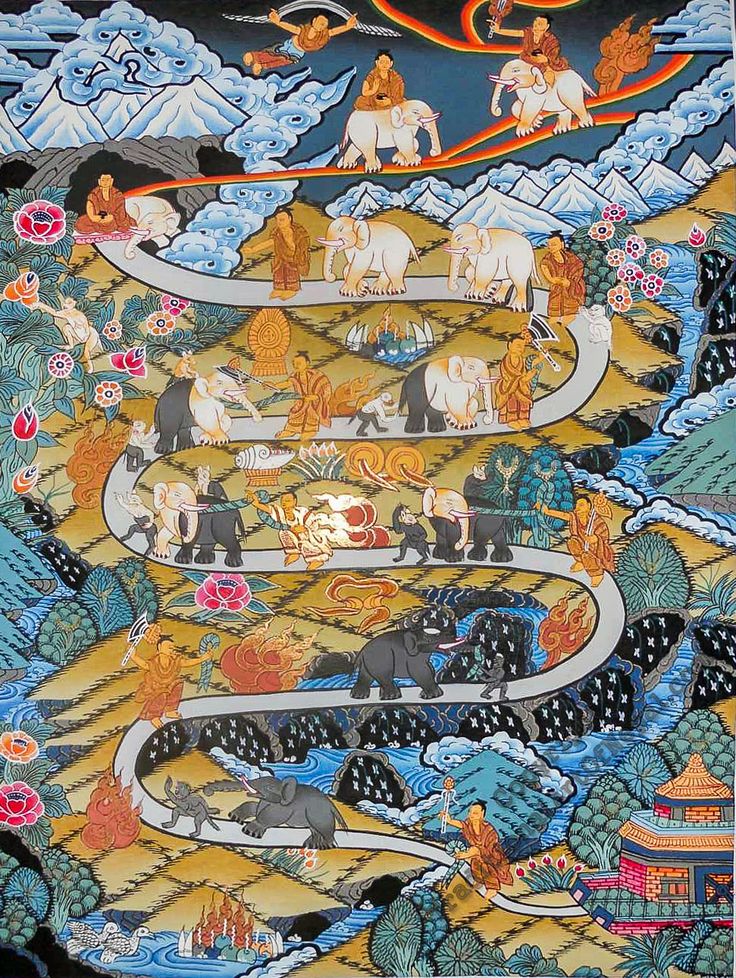

Not only do Tibetans meditate, but even the nine stages of samatha (ending with vipassana) meditation are reproduced, comic-strip fashion, in thangkas and wall murals in the antechambers of monasteries and temples. In these paintings, the mind is depicted as a black, unruly elephant that gradually becomes white and peaceful as the meditator trains it with the lasso of mindfulness and the goad of alertness. A monkey and a hare represent subtle mental factors the meditator must contend with. Along the winding path the meditator takes are flames representing the effort to be expended at certain stages in his journey. At the end of the path, the meditator is depicted holding the sword of Manjushri (symbolizing the realization of emptiness or sunyata) and entering the meditation of “higher insight”—lhakthong or vipassana.

I think that many people in old Tibet, especially children, must have seen this illustration at one point or another and had some idea of what it was all about, while practitioners, lay or clergy, would have at some point in their lives received instructions on this meditation technique and incorporated it into their daily practice.

Movement as Meditation

As a daily practice, however, most Tibetans preferred more active forms of meditation. This was almost certainly dictated by the cold of Tibet, especially on winter mornings when even the water bowls on your altar would be frozen solid. We did not have central heating, so you had a number of meditation methods involving movement: kora (circumambulation), chak (prostration), kyangchak (full prostration), and even the cham mask dance.

The most popular practice for laypeople, especially in the early mornings, was the kora or circumambulation, preferably in places where there was a monastery or sacred monument you could walk around. In Lhasa, the most popular walk was the Lingkor, or the greater circuit that goes around the Chakpori Hill, the Potala Palace, and inner Lhasa, including the Jokhang, for a full five miles or eight kilometers. On average, it took you two hours to complete the circuit. A much shorter circuit would be the Barkhor kora, which just went around the Jokhang temple.

But does walking help you meditate? Zen Buddhism has the kinhin walking meditation, a practice found in other Buddhist traditions as well. In the Tibetan tradition, practitioners repeatedly recite a mantra while walking and meditating. Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche, the Tibetan meditation master, says that walking meditation is designed to bring our body and mind together, and help integrate meditation into everyday life. [2]

Walking meditation, if done right, can have real benefits. There is a story that the Fifth Dalai Lama was looking down from the roof of the Potala at his subjects walking the Lingkor circuit. One day he noticed an old man who appeared to have the goddess Tara floating above him as he walked. The Dalai Lama had an official summon him to his presence and then asked the old man what he did during his kora walk. The old man replied that he recited the Tara mantra and tried to meditate on the deity. His Holiness asked him to recite the mantra, which the old man did, making a couple of mistakes. The Tara mantra—”Om Tare Tuttare Ture Svaha”—can be tricky to pronounce, so His Holiness helped correct him and sent him on his way. The next day, when looking down from the Potala, he saw the old man walking, but there was no goddess floating above him. His Holiness realized that the man was now focusing on his pronunciation rather than his visualization. So, he instructed the old man to resume his former routine, mistakes and all.

Prostration as Practice

Pilgrims may travel for months or years, prostrating themselves along the way from their remote homes to holy cities like Lhasa. Prostrations and full prostrations are also meditation techniques, as is the meditation pilgrimage itself. People who perform this practice are called “kyangchak lama.”

In a teaching he gave at Thimphu, Bhutan, Jamyang Khyentse Rinpoche informed his (mostly Bhutanese) audience that such practices as kora, prostrations, turning mani wheels, and even going on pilgrimages were all different ways of practicing vipassana meditation. “Lighting a lamp, printing a prayer flag, pouring water in a ting bowl—every step you take in pilgrimage, even without thinking, every small step is vipassana.” [3]

Of course, there were moments when a trained meditator was required to remain stationary for considerable lengths of time, so for those specific practices the tummo, or internal heat generating meditation, was likely invented. (Tummo is one of the six practices attributed to Naropa.) Another invention to help with maintaining proper meditation posture was the gom-thag, or meditation belt.

Perhaps the most well-known monastery in Tibet where such meditations were practiced was the Zhalu monastery in Tsang, where practitioners engaged in tumo and even the partial levitation that Tibetans called bep, and in particular the lung-gom, which was required for the long-distance running from Zhalu monastery to the Potala (180 miles) once every twelve years, particularly during the Monkey year.

Challenging Colonial Misrepresentations

I bring this up because L. Austine Waddell, the principal Victorian mis-interpreter of Tibetan Buddhism—or “Lamaism” as he dismissively referred to it—discussed the meditators of Zhalu in his book Lhasa and its Mysteries. When accompanying the Younghusband military expedition to Tibet in 1904 he took time to visit the Nyang-tö Kipuk meditation cells near Zhalu, where he describes the “sickening sight” of the “miserable wretches” who were “immured for life in pitch dark cells.” Waddell claims that this “repulsive form of religious observance of the semi-savage Tibetan” came about because “the average Tibetan, and especially the priest or ‘Lama’, is extraordinarily low in intelligence.” [4]

I was a friend of the late Rikha Lobsang Tenzin, a scholar and Education Secretary of the exile Tibetan government. One night he told me about his experience as a young meditator at Zhalu. He mentioned that the cells were sealed from the front, and you collected your food from a small, curtained aperture. But Rikha said that the cells were not dark—in fact, the back was open to a cliff-edge view. He also told me that a small stream ran through the row of cells, providing fresh water. Each meditator had a thighbone trumpet that he blew in case he needed medical help or wanted to consult his meditation teacher. No one was immured for life. Lobsang Tenzin-la told me that initially he found the isolation challenging, but after a month he found the whole experience uplifting and peaceful and felt no desire to come out of his cell. But then the March 10 Uprising happened, and all cells were opened, and the meditators sent home.

The Problem of McMindfulness

Tibetan and other Asian meditation traditions need no defending, but I am concerned about a worrying trend in the West: the “McMindfulness” (get the book) [5] commodification of mindfulness meditation, which strips away the ethical foundation of traditional Buddhist meditation and turns it into a tool to reduce stress, increase productivity, and more effectively run your business. This commodification disconnects meditation from its deeper purpose—the cultivation of self-realization and liberation (tharpa)—and reduces it to a mere technique for self-optimization.

There is also the persistent Western residual colonial attitude, an unceasing need to “take over”—countries, cultures, Mars? or even Buddhism itself. When that endeavor proves difficult, the response is often to rubbish traditional Buddhism and demonstrate that a Western construal and exposition of it is more “rational,” “scientific,” or “secular.” Something like this comes through in Sam Harris’s claims (in a conversation with Robert Wright) about Buddhist meditation practices:

“If you look at societies that have been Buddhist historically, they have fairly unimpressive political fortunes, and people have argued that Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge was made possible in large part because of a Buddhist spirit of quietism that incubated that kind of extremism.” [6]

This argument is deeply troubling. To suggest that “Buddhist quietism” enabled the Khmer Rouge genocide ignores the actual causes: French colonialism, Pol Pot’s Maoist-inspired ideology, the devastating American bombing campaign (approved and overseen by Henry Kissinger) that dropped hundreds of thousands of tons of explosives on a small, peaceful country, and the deliberate targeting of Buddhist monks and institutions by the Khmer Rouge itself. Blaming Buddhist philosophy for atrocities committed against Buddhists is not just ahistorical—it’s an inversion of reality that serves to absolve the actual perpetrators while denigrating an ancient wisdom tradition.

Conclusion

The assertion that Asians don’t meditate reveals more about Western assumptions than about Asian Buddhist practice. Meditation in Tibet was not a marginal practice reserved for monastics or a privileged class but woven into the daily lives of ordinary people through kora walks, prostrations, mantra recitation, and yes, seated meditation. The diversity of these practices—adapted to climate, lifestyle, and individual capacity—demonstrates the sophistication and practicality of Tibetan Buddhist tradition.

Rather than dismissing or repackaging traditional Buddhist practices to suit Western preferences, a serious seeker or student might do better to learn from them with humility and respect for their cultural context and ethical foundations, and in the fullness of time for his or her own spiritual fulfillment.

References

[1] Robert Wright, “Why Buddhism Is True” (promotional talk), YouTube, from 46:40 to 46:59. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vJZTrVlSBTY&t=2027s

[2] “How to do Walking Meditation with Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche,” YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zZnNO1myCMg

[3] “Lhakthong (Vipassana),” teaching by Jamyang Khyentse Rinpoche, November 27, 2019, Thimphu, Bhutan, from 27:30. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b_T0CA0XeWI&list=PLuGJJiAjMz2hsSvpMtKYZCQFx5C0FXzcp&index=178&t=6s

[4] L. Austine Waddell, Lhasa and its Mysteries (London: Methuen, 1906).

[5] Ronald E. Purser, McMindfulness: How Mindfulness Became the New Capitalist Spirituality (London: Repeater Books, 2019).

[6] Sam Harris, “Why Buddhism is True with Robert Wright,” 2018, from 26:50-27:10. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=McwHELx7Oa4&t=1628s