This rambling essay is based on a rambling talk I gave to Tibetan students at the Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) in Delhi on the 1st of April 2019. I had been invited to speak at the Dawa Norbu Memorial Lecture, organized (since 2015) by Tibetan students and staff to honor the memory of Professor Dawa Norbu-la, the first Tibetan academic to be appointed at JNU as professor of Central Asian Studies. I made a hash of my talk. A 20 hour flight, jet lag and an injudicious self-prescribed nostrum, didn’t help. But the hundred or so curious, outspoken, eager-to-know students just brushed aside my incoherence, and bombarded me with arguments and questions –– even on issues considered terrifyingly taboo in our subservient exile society. I had a great time.

REFLECTIONS ON SOME GREAT WOMEN WARRIORS, RULERS, DIPLOMATS, SCHOLARS, BUSINESS ENTREPRENEURS AND REVOLUTIONARIES OF THE PAST

We live in a time when women’s issues feature prominently in a variety of fields: politics, education, religion, sports, entertainment, finance and economics to name a few, and are front and center in all related discussions. Yet, this should not obscure the underlying historical reality that women have, till very recently and even in so-called “enlightened” societies, been denied the basic right to participate in all such areas of human endeavor. The right to do so on equal terms with men is still another and far from settled question.

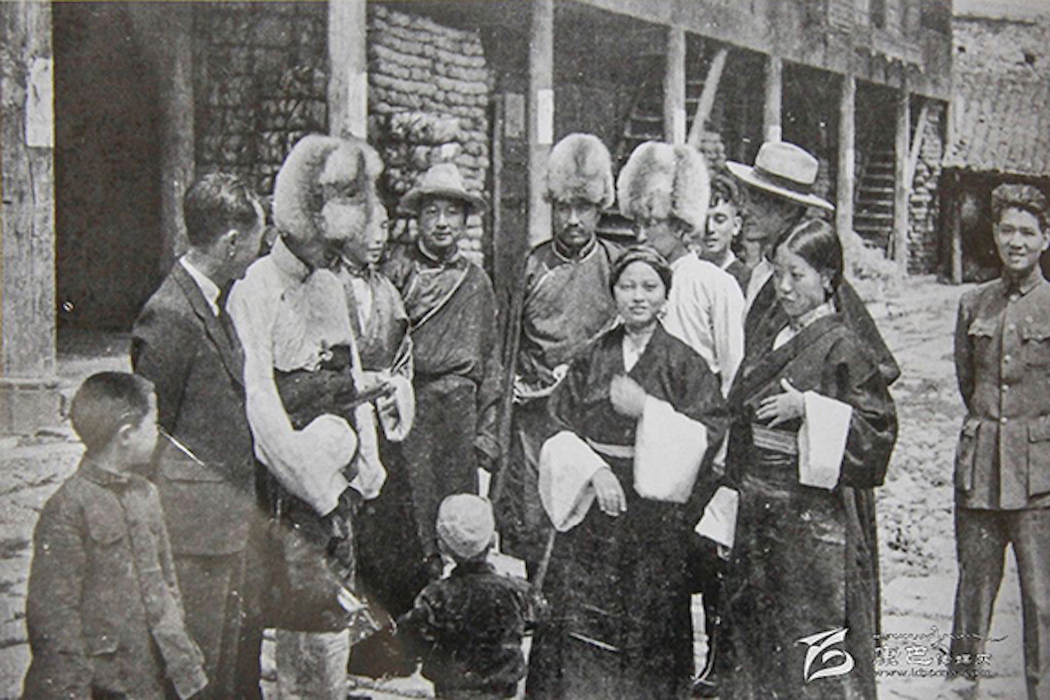

Tibetan society before 1950 was insular, conservative and, of course, not democratic and modern. Hence the general assumption has been that the position of women in old Tibet was consequently an inferior or second-class one, as it still is in many traditional societies in the Middle East, North Africa and Asia. But in numerous accounts of visitors and travelers to pre-1950 Tibet one comes across positive and even laudatory comments on the role of women in Tibetan society. These observations surprised me initially, but on consistently encountering them in various travelogues and reminiscences, I was impressed enough to dig a little deeper into these remarks, a few which I have reproduced below, and study how substantial the fundamental reality was for women in old Tibet:

An Italian photographer in Central Tibet, 1948: “Women in Tibet have a very high social position, compared with women of other Asian countries.”[1]

An American explorer and socialite in Lhasa, 1935: “These wives of Tibetan nobles possessed a quality extraordinarily rare in women of the Orient. Freedom was part of their tradition, for their country had never known the Indian system of purdah or the Chinese custom of infanticide, little girls in Tibet being as welcome as boys. Every Tibetan woman has the right to select her own husband, to run her own household, and to own property. In the old days when the country was divided up into a number of small principalities, some districts were ruled by women.”[2]

Another American traveller in Muli, Eastern Tibet, 1928: “The hostess, like a Tibetan lady of high rank and of acknowledged equality with men, showed none of the Chinese woman’s desire to mask her feelings or to retire into the background.”[3]

A British trade agent who lived twenty years in Tibet: “Women have much influence in Tibet, both in the home-life and in business. Although no woman shares in the administration of State affairs, they exercise considerable unseen influence in many directions.”[4]

An American missionary couple in Amdo in the 30s: “They (the women) rode horses through town like men… the Tibetan women are much different from the Chinese in that they are perfectly free, and a Chinese woman may hardly speak to a man”.[5]

The Chinese consul-general in Lhasa from 1944 to 1949: “Western writers have remarked on the free and respectable status of Tibetan womanhood. It is true that they do not bind their feet, nor do they observe purdah. And, as a rule they control the family purse strings.” [6]

A French scholar and traveller in 1948: “A European or an American has a great deal to learn from Tibet, not only in matters of mysticism or religion but also in social customs. Women have a higher status in Tibet than anywhere else in Asia. Not only are they perfectly free and they inherit wealth on equal terms with men but they can often become head of the family and give their name to their husbands. Divorces are easy but expensive.[7]

FINANCIAL INDEPENDENCE OF TIBETAN WOMEN

The last two observations point to the economic self-sufficiency that many Tibetan women seemed to have acquired and which most likely underpinned the freedom and independence they enjoyed socially. Even to the casual observer then, it was clear that in much of old Tibet, particularly in the towns and cities, a large portion of the retail trade was in women’s hands. A popular and award-winning novel from Lhasa, The Secret Tale of Tesur House (1994), by a well-known Tibetan writer tells the story of the wool-trade in the 1940s, and how a destitute orphan girl named Pema became the head of a major trading house in Lhasa.[8]

A few years ago a Tibetan historian, Yudru Tsomo, of Sichuan University, published an interesting study of the traditional role of Tibetan women in business and trade. In her article on the major tea-trade at Dhartsedo (ch. Kangding) she writes that, of the thirty to forty principal Tibetan firms (ch. guozhuang tib. ajakhaba) or companies handling the tea trade, many were run by women. Dr. Tsomu also adds “over the course of the early twentieth century, these institutions went from being managed by men to being managed mostly by and identified with women.”[9]

Dr. Tsomu quotes the Chinese historian Ren Naiqiang on the comparatively higher status of women in Tibetan society: “Tibetan (Ch. xifan) women manage property and are the heads of families. Women can inherit family property and official positions. [They] allow men to marry into their families.”

The legal system of pre-1950 Tibet appears not to have been hostile, if not (wholly) supportive of the financial independence of Tibetan women. The head of the famous Andrugtsang mercantile family in Lhasa died in 1942 and the rest of the extended family agreed to appoint a cousin, Gompo Tashi, as the “CEO” of the trading house.

The wife of the deceased family head, Kesang Lhamo, rejected the family decision and refused to give up the business holdings she controlled. She brought up her case before the Lhasa magistrates. She also refused to accept any mediation regarding control of the Andrugtsang wealth, and when one courthouse decided against her she would present the case to another government department. Finally she even petitioned the Tibetan Army Headquarters at the Shöl administrative complex below the Potala where the dispute went on unceasingly till 1959.[10]

Financial independence gave Tibetan women the freedom to ignore or disregard male (particularly priestly) condemnation of their lifestyles, in particular the use of Western cosmetics that were in vogue from the 1930s. This is what a Lhasa woman had to say about the matter, in a wonderfully biting verse that looses much in translation.

I’ve put on the white (face powder) myself, I’ve put on the red (lipstick, rouge) myself. Don’t be upset, you honorable folks. I’ve used my own purse to pay for it, myself.

Karpo nga-ras jhug-yöd, marpo nga-ras jhug-yöd, lhan-gai gong-pa ma-tsum, nga-ras ba-kug trog-yöd)

དཀར་པོ་ང་རས་བྱུགས་ཡོད། དམར་པོ་ང་རས་བྱུགས་ཡོད། ལྷན་རྒྱས་དགོངས་པ་མ་ཚོམས། ང་རས་སྦ་ཁུག་དཀྲོག་ཡོད།

Women in Saudi Arabia were only granted the right to drive in 2019, so it might be mentioned that all women in Tibet customarily rode horses as men did. Tibetan women were also not subjected to absurd sexist rules of modesty as in Victorian England, where women were required to ride side-saddle. In the mid-1950s when motor-biking became the rage in the Holy City, one of the first and most glamorous of bikers was the celebrated Lhasa beauty, the younger Lady Lhalu Sonam Deki, who roared around the holy city on a black BSA 500.

ROLE OF WOMEN IN RELIGIOUS LIFE

Women had no major role in the great religious institutions, particularly in the Gelukpa monastic universities, and also in the clerical power structure of the Tibetan government. There were important female incarnations as Samding Dorje Phagmo and also some important nunneries, but these were admittedly minor compared to the scale and importance of the male priestly institutions.

Yet in terms of spiritual practice it should be stressed that there were no taboos or restrictions for women to worship in temples and monasteries, as you had in India till September of last year (2019) when the Indian Supreme court ruled that barring females of menstruating age from temples was discriminatory and illegal.

Tibetan women may not have been allowed to remain within monastic premises in the evening in observance of Buddha’s vinaya code for monks, but this rule also applied to men who were not allowed to stay in nunneries in the evening.

Although women did not have a significant role in institutional religion in Tibet, they nonetheless played an important and recognized role in spiritual practice and teaching. The dakani Yeshe Tsogyal, although described as Padamasambhava’s principal spiritual consort, was essentially a spiritual master and teacher in her own right, and is sometimes referred to, these days, as the “Mother of Tibetan Buddhism”.

Then we have Machik Labdron, the renowned 11th-century Tibetan tantric Buddhist practitioner, teacher and yogini who originated several Tibetan lineages of the Vajrayana practice of Chöd. I have earlier mentioned Samding Dorje Phagmo the highest female incarnation in Tibet and the third highest-ranking person in the hierarchy after the Dalai Lama and the Panchen Lama. In the last century we had Shukseb Jetsunma Chönyi Zangmo (1852–1953) who was the most well known of the yoginis in the 1900s, and was considered an incarnation of Machig Lapdron. She was the abbess of Shukseb nunnery, and was a Nyingma Tibetan Buddhist teacher.

Female spiritual teachers and personalities are particularly recognized and exalted in Tibetan theatre. In the Ache Lhamo opera three principal plays: Nangsa Wöbum, Drowa Sangmo, and Sukyi Nyima, celebrate the contribution of Tibetan women to spiritual life in Tibet. In fact these three operas are named after their female protagonists.

WOMEN IN POLITICS AND NATION BUILDING

But one could safely say that women played no role in formal official and political life of old Tibetan society. The fundamental organization of ancient Tibetan society, under the tsanpo emperors was military based. The whole political structure, which became the Tibetan Empire was based on warfare. In this system land inheritance was conditional to having a male warrior in the family to serve in the Imperial army. All land in Tibet theoretically belonged to the state. It could be resumed by the state if there were no men in the household to serve the emperor. Families got around this legal requirement by the institution of makpa or the bridegroom “warrior” substitute. The makpa not only left his own family to join his wife’s household, but also had to legally take on the name of his wife’s family. The position of the women in such a familial arrangement was not undermined by this particular fiction, and often in such households women also maintained financial and administrative control.

Nonetheless formal official positions in the Tibetan government and the church in old Tibet could only be assumed by men. This of course did not mean that Tibetan women had no influence in politics and society. There is mention of women’s involvement in national political life from the beginning of Tibetan history.

One of the principal personalities in the creation of the Tibetan Empire was a woman, Semarkar, the sister of Emperor Songtsen Gampo (547?– 649). The princess Semarkar was sent as a bride to the Zhangzhung King Ligmigya and became his queen. The Old Tibetan Chronicle tells us that Semarkar was sent to Zhangzhung not simply as a bride but to rule alongside Ligmigya, “to practice state power”.[11] Sometime after the wedding, Songtsen sent a minister to Zhangzhung to get a report from Semarkar. Semarkar sent a hidden message back to Songtsen in a song, which some scholars have interpreted as saying that Ligmigya was not to be trusted and that Songtsen Gampo should wage war –– even alluding as how he should attack Zhangzhung. In 644 BCE, possibly acting on intelligence sent by his sister, Songtsen Gampo led an invasion with his army and conquered Zhangzhung. A verse from Semarkar’s song to her brother describing her plight:

The land that has fallen to my lot is the Silver Castle of Khyunglung. All around others say: ‘Seen from without, it is a rocky escarpment! Seen from within, its all gold and treasure!’ But as for me and my opinion, I wonder, is it good to live in? How sad I am and lonely![12]

Another important imperial lady mentioned in the Old Tibetan Annals was Trimalo Triteng the consort of the Emperor Manglon Mangtsen, the grandson of Songtsen Gampo. During the reign of Manglon Mangtsen the Gar clan was in control of imperial affairs –– the emperor being largely a figurehead. Trimalo’s son Tri Dusong was, at the time of his father’s death, too young to rule and the Gar clan continued to control civil and military affairs. When Tri Dusong came into adulthood, Trimalo helped arrange the overthrow of the Gar clan. TriDusong and his army attacked and defeated Gar and his supporters. Many supporters of Gar were executed, while others managed to find refuge in China. Trimalo represented the empire during the times when Tri Dusong was in battle. When Tri Dusong died in 704, Trimalo continued to involve herself in imperial affairs, acting as regent. [13

Tri Dusong had two sons. The older was unfit. The younger son, Tri Detsuktsen was one year old at the time, so Trimalo continued to fill the power vacuum, communicating with China and ultimately arranging the marriage between a Chinese princess and her grandson Tri Detsuktsen. Trimalo ruled until 712, the year of her death. In that same year, Tri Detsuktsen was enthroned formally. Empress Trimalo had been compared by historians on Tibet and China to the extraordinary Empress Wu Zetian of the Tang Dynasty and founder of the Zhou dynasty, who is to date the only woman ruler in China’s history.

For further information on Tibetan women during the Imperial period readers are directed to the article by Helga Uebach, “Ladies of the Tibetan Empire”, which has been a great help in my own account of these two great ladies.

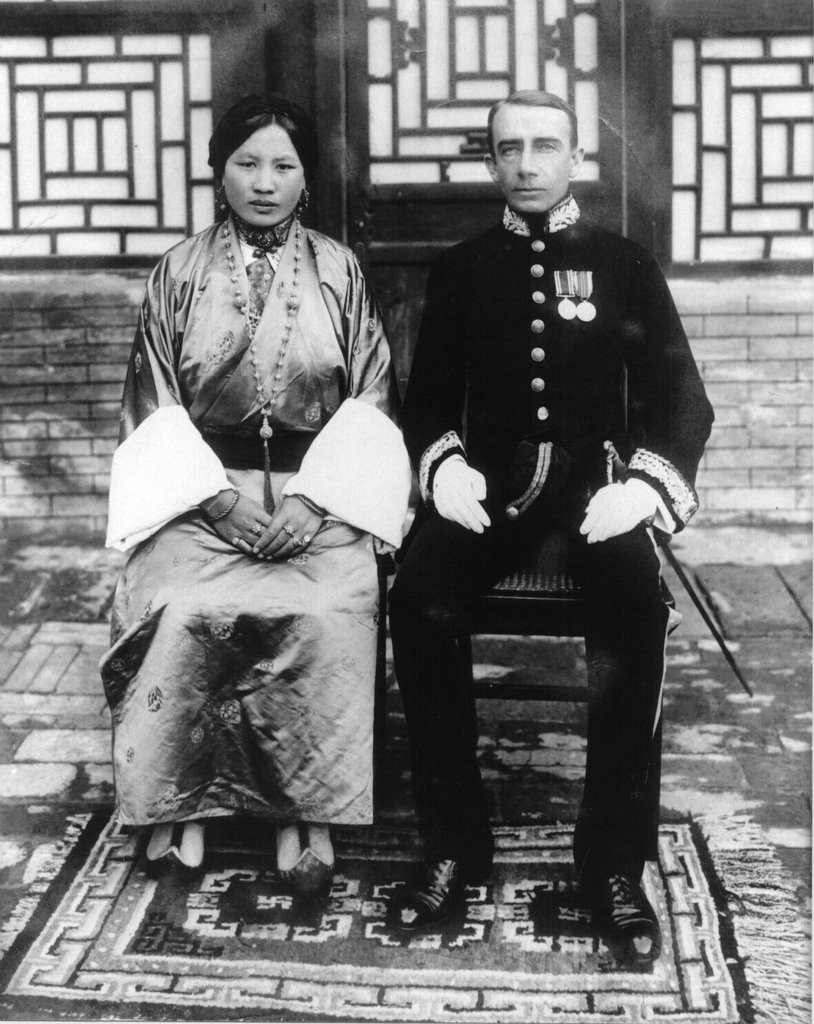

An important Tibetan female political player from more recent history was the queen of Sikkim, Yeshi Dolma. She was Lhasa aristocracy, the daughter of the Lheding family. Her uncle a dapon,“the Lhasa General” in British accounts of the Younghusband invasion of 1904, was killed at the battle of Guru. She was married in Lhasa in 1882 to Thutob Namgyal prince of Sikkim.

British intrusion into Sikkim began in the early nineteenth century. And step-by-step, in the usual manner of colonial acquisitions Darjeeling and other areas were detached from Sikkim. The king Thutob Namgyal was by most accounts an indolent character and Yeshi Dolma took it upon herself to become the driving force in the opposition to British expansion into Sikkim and Tibet. One project in this effort headed by the Queen was the compilation and writing of the History of Sikkim[14] (Hbras ljong rgyal rabs) that appears to have been a nationalist or nativist response to the official British Gazetteer of Sikhim. The authorship of this history is jointly attributed to both the king Thutob Namgyal and his queen Yeshi Dolma, but I have been told by a historian on Sikkim that it was largely the work of the queen. In the end Yeshi Dolma’s efforts proved to be in vain.

Yet in spite of her hostility to British rule she appears to have gained the respect, even the admiration of, British resident John Claude White, who notes that she was a petite yet striking figure, but goes on to describe her other more impressive qualities:

“She is extremely bright and intelligent and has been well educated … she talks well on many subjects, which one would hardly have credited her with a knowledge of, and can write well. On the occasion of Queen Victoria’s diamond jubilee, she personally composed and engrossed in beautiful Tibetan characters the address presented by the Sikhim Raj.

Her disposition is a masterful one and her bearing always dignified. She has a great opinion of her own importance, and is the possessor of a sweet musical voice, into which she can, when angry, introduce a very sharp intonation. She is always interesting, whether to look at or listen to, and had she been born within the sphere of European politics she would most certainly have made her mark, for there is no doubt she is a born intriguer and diplomat.”[15]

WOMEN IN WAR AND REVOLUTION

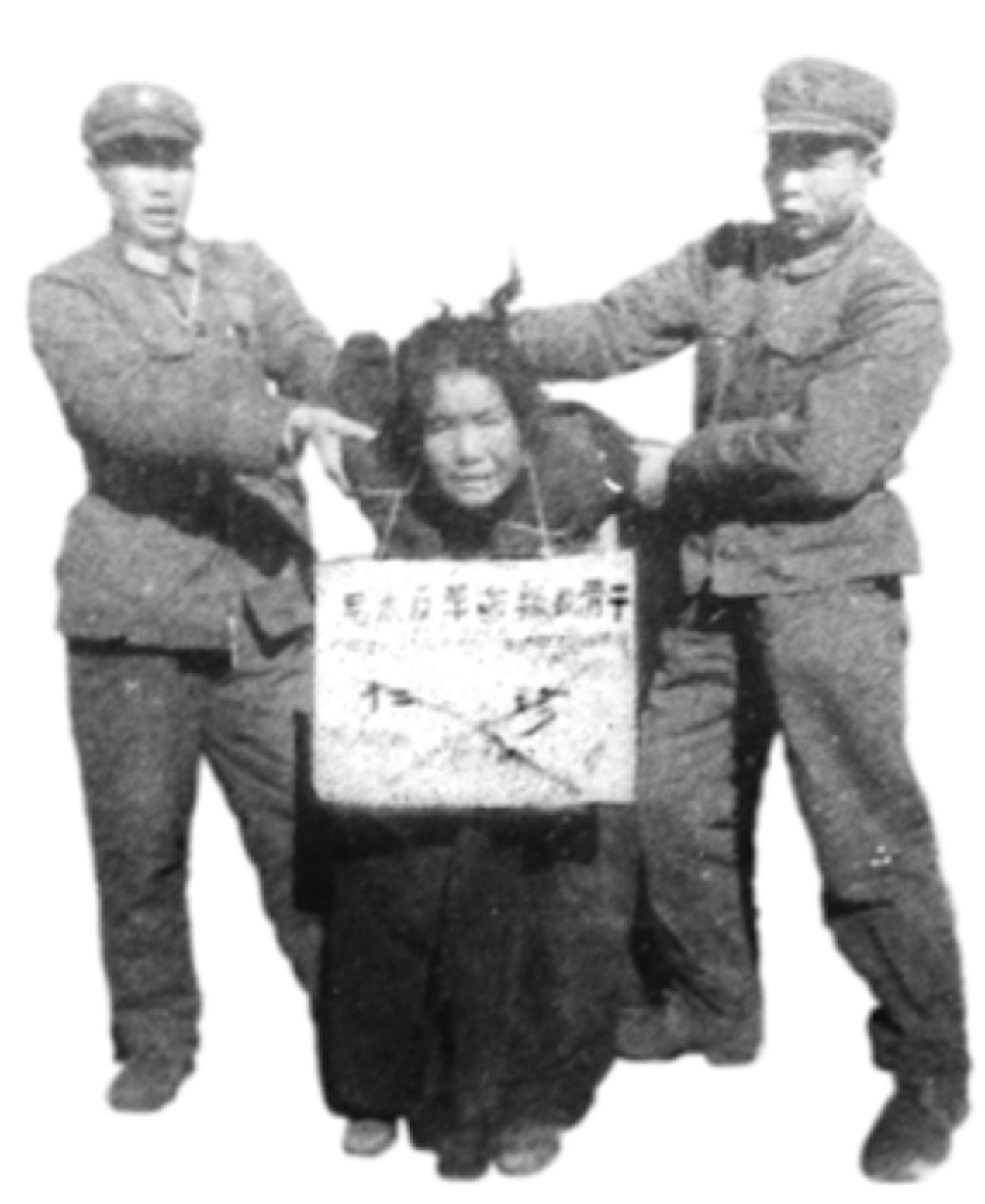

Tibetans are all aware of such outstanding and courageous women as Galingshar Chöla and Gurteng Kunsang, whose names are generally preceded by the epithet “pamo” or “female warrior”. These two women were the principal figures in the organization of the “Women’s March” on March 12, 1959, against the Chinese military occupation of Tibet. Both women were subsequently arrested by the PLA. A joint statement by two eyewitnesses in 1961 describes the fate of the former. “On October 21, 1959, a 60-year old nun Galingshar Anila was taken around the Barkhor in Lhasa. The Chinese ordered the people to beat her but no one would do so. Then the Chinese gathered some thieves and beggars gave them some money and had them beat her at her house… She died on the 31st of the same month.”[16]

Gurteng Kunsang, who was a niece of Tsarong Dasang Dadul was incarcerated at the central prison at the headquarters of the Tibet Military District (qingqu silingpu).

But Kunsang kept up her defiance in prison and refused to make a confession or collaborate with her Chinese captors in any way. She was executed at the end of 1970 with fifteen other prisoners.[17]

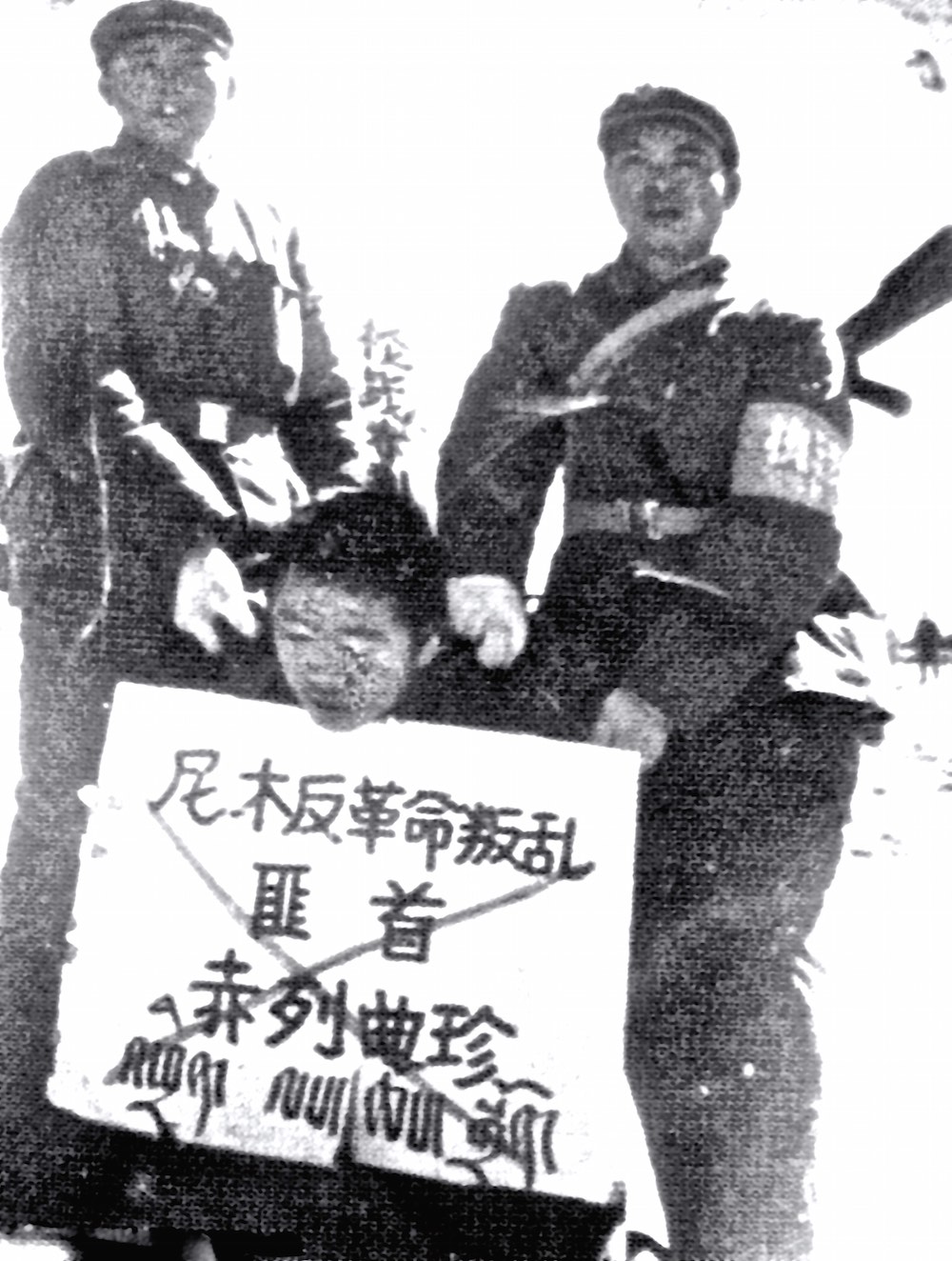

During the 1956 Uprisings in Eastern Tibet we know of at least two women Ani Pachen Lemdatsang of Gonjo and Gyari Dorje Yudon of Nyarong, who personally lead their male tribal warriors in violent insurrections against the PLA.

But for this article I would like to offer a more in-depth discussion on two other Tibetan women leaders whose separate struggles against Chinese imperialism were revolutionary in a greater nationalistic sense and captured the imagination of Tibetans beyond their immediate locality and period

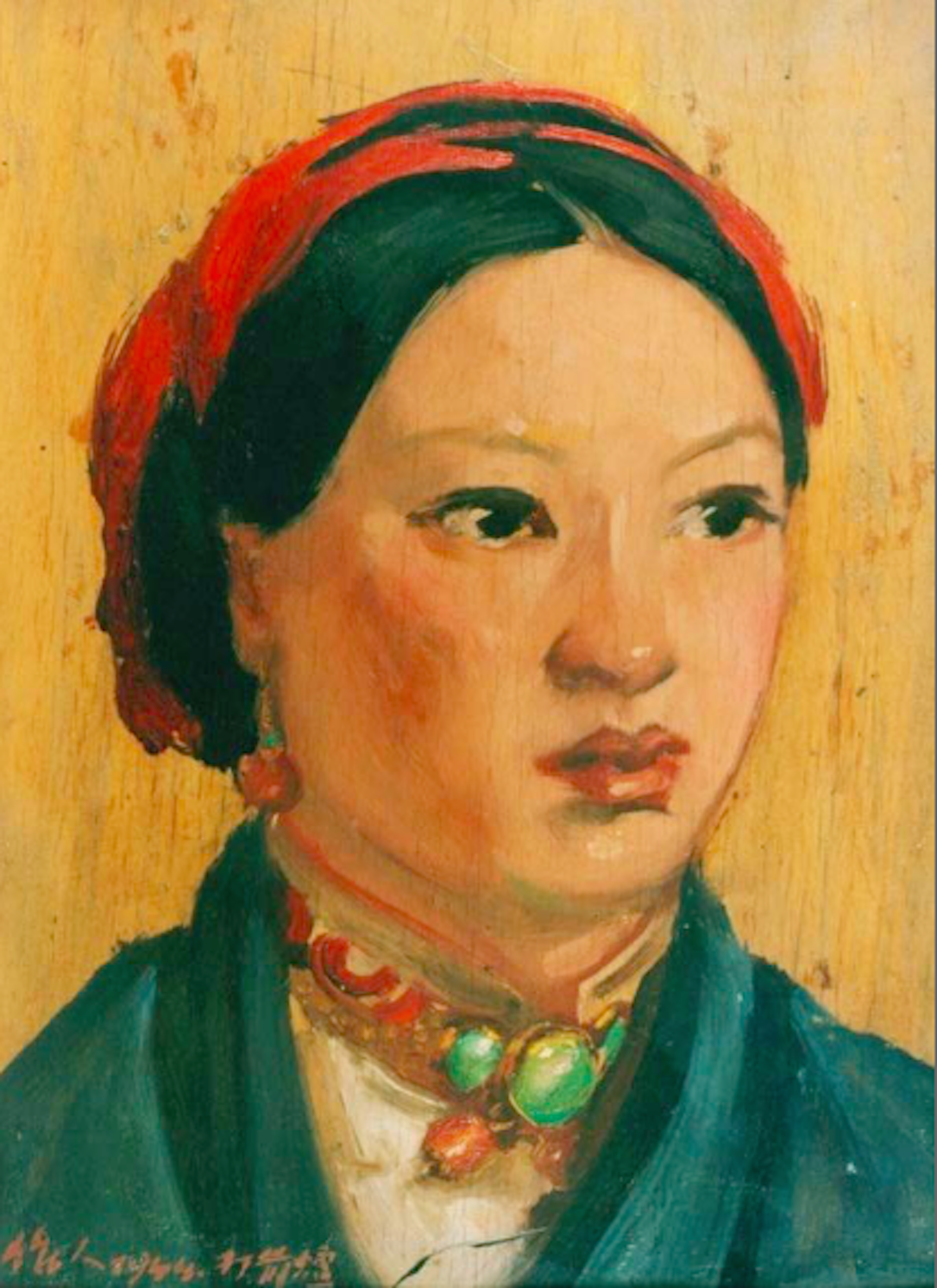

Gyari Cheme Dolma rose up against the Sichuan warlord/governor Liu Wenhui in 1936. She and her warriors attacked the Castle of the Female Dragon, the district headquarters of Nyarong and drove out the Chinese garrison there. The Chinese came back in greater numbers, forcing her to retreat, but she recaptured the castle in 1939. Finally the Sichuan warlord army, reinforced with regular Guomindang troops attacked Cheme Dolma and forced her to retreat back to her tribal land in Upper Nyarong. They laid siege to the family castle (Gyari phodrang) and burnt it to the ground. Cheme Dolma came out of the burning building with a sword in her hand, apparently not prepared to surrender, and received a number of gunshot wounds. Finally she was disabled by a bullet to her leg and captured.

She was taken in chains to the Castle of the Female Dragon and executed by a firing squad. Before she fell, she was said to have cried out these words: “Never will I submit to the Chinese … I die for the freedom of my people and my land. People of Nyarong, do not forget me.” Her words resonated throughout Eastern Tibet. Bapa Phuntsog Wangyal, the Communist agent mentions the execution of Gyari Cheme Dolma in the lyrics of a revolutionary song he wrote that was published in the Tibetan Mirror Newspaper in Kalimpong in 1944.

In 1935 Gyari Cheme Dolma is said to have taken her warriors to Tahu and attacked the Red Army that was marching through the district. Mao Zedong when recounting the “Long March” to American Communist propagandist, Edgar Snow, told him that one particular “Mantzu Queen (most likely Cheme Dolma) had an implacable hatred for Chinese of any variety”. Her mountaineers sniped at the Reds and rolled huge boulders down to crush them and their pack animals. “This is our only foreign debt” Mao told Snow “humorously”, “and some day we must pay the Tibetans for the provisions we were obliged to take from them.”[18]

During the Cultural Revolution when murderous conflicts between Red Guard factions were taking place throughout the villages and towns of Tibet, the most famous and violent of these struggles between the Rebel faction and the Alliance faction took place in the district of Nyemo. This uprising captured the imagination of the Tibetan people not only because the leader of the Nyemo Rebel faction was a young woman, and a nun at that, but as she transformed Mao’s supreme political campaign into a patriotic religious war against Communist Chinese rule. Even Chinese officialdom admitted that the Nyemo Uprising was an “… armed counter-revolutionary revolt … paralleling the 1959 uprising.”[19]

Trinlay Chödön the nun of Nyemo or “Nyemo Ani” as Tibetans remember her, had since the age of twelve been a nun at a Kagyüpa nunnery at Phusum village in Nyemo, and, apparently happy with her spiritual life. Her life was disrupted traumatically when the monasteries and temples were closed and lamas were “struggled”, executed and even driven to suicide. She started having strange dreams and visions, and began going into trances, uttering prophecies and even healing people. She became well known throughout the district. She joined the Nyemo Rebels at a crucial moment in their struggle to wrest administrative power from the powerful local Alliance faction. Armed with swords, spears, muskets and homemade bombs they also attacked PLA outposts and camps –– initially with considerable success. A Norwegian scholar Hanna Havnevik writes “…it is said that she (Nyemo Ani) had a network of contacts stretching from Mount Kailash to Kham, and that she organized a guerrilla movement which killed many Chinese.”[20]

Finally in the summer of 1969 several thousand PLA troops in hundreds of trucks invaded Nyemo. After three days of intense fighting and the death of hundreds of Rebel fighters, many who committed suicide by jumping in the Nyemo River –– the nun and some of her followers escaped to the mountains. She was eventually captured and taken to Lhasa with twenty-nine other prisoners. She was publicly executed in early 1970 at Dodé near Sera monastery.

Some feminists in the exile Tibetan world appear to have embraced our revolutionary nun. A Tibetan student at Columbia University wrote in a blog post of a discussion on the Nyemo Revolt where her friends and classmates spoke of Nyemo Ani as “… the Joan of Arc of Tibet … and this isn’t a crazy parallel either. Like Joan, Ani Trinley, so young — around the age of 28, claimed that she was possessed by a divine entity as she led the ’69 revolt. Trinley Chodron is important not only because she was a remarkable woman who led a resistance against incredible odds, she matters too because she is part of a battle against the revision of our history. The Chinese have attempted a million ways to distort the true desires of the Tibetan people. Ani Trinley, with her humble roots and her peasant following, shows how the Tibetan people fought against the Chinese occupation of Tibet. She is a precious example of our history, and history only survives if we remember.”[21]

We must, of course, remember the young women warriors who in recent years gave up their lives to protest Chinese Communist rule. Their sacrifice for the freedom of their people and nation requires a separate and comprehensive study.

SOCIAL FREEDOM AND EQUALITY FOR WOMEN

The social freedom that Tibetan women enjoyed, particularly in Central Tibet and in Lhasa, has often been noted by foreign visitors. There was none of the custom of purdah or zennanna that prevailed in the sub-continent till recently, or as in traditional China where the womenfolk were strictly confined to separate women’s quarters and did not interact with guests. In some instances Chinese women even had their physical movements restricted by such barbaric practises as “foot-binding”

In Tibet not only did the lady of the house receive guests and socialize with them, it was in fact required of women to dine and drink with male guests and take part in the conversation. A British official Basil Gould describes his meeting with the senior Lady Lhalu, Yangzom Tsering (nee Shatra, c.1880 – 1962) :

“…a member of high society. One of the events of the Lhasa season was an annual luncheon party that she gave to the Cabinet and other high officials. Her hospitality was so urgent that often the fate of at least a few of her guests was ‘Where I dines I sleeps’. She had a fund of jokes and stories which were reputed to be broad. I doubt whether even in England men and women live on such natural and easy terms as in Tibet’ [22]

Such social freedoms were not only the preserve of the aristocracy but widespread in all classes. In Lhasa, women drank and made merry publicly during the summer and autumn picnic seasons. There was no social stigma in drinking in public or even being tipsy (at least occasionally). In fact when a day-long opera performance would conclude at the Norbulingka Palace and the merry audience would walk back to the city, many Lhasa citizens who had not gone to the opera would turn out by the Norbulingka road to watch the returning men and women staggering home, supporting each other in their revelries and singing opera aria’s (namthar). This pastime even had a name, “mi-thay” or “people watching”.

Once as a schoolboy in Darjeeling, I passed by a large group of Tibetan women on the Chowrastha road. They had gone for a Sangsol (incense offering) ceremony at the Observatory Hill, or Gangchen as Tibetans called it, the site of the oldest Buddhist temple in the district. They were returning home, arm-in arm, singing songs, strolling down the main Chowrastha and Nehru Road where all the posh stores were located. They were dressed in their best silks and jewelry and all happily drunk, oblivious of the amused stares of passersby. Some sheepish looking Tibetan men and servants accompanied them.

LEGAL EQUALITY FOR TIBETAN WOMEN

The earliest Tibetan legal code, commonly attributed to Songtsen Gampo, has one line “Do not to listen to the words of women”. This has often been quoted to demonstrate the lack of legal freedom and equality for Tibetan women

But by the time of the establishment of the Fifth Dalai Lama’s Ganden Phodrang government, laws dealing with women’s right to property and divorce had evolved to a point where it could be compared favorably to those in other parts of Asia, the Middle East and Africa. I quote from Rebecca French’s “Tibetan Legal Literature: The Law Codes of the dGa’ ldan pho brang”[23] from the section dealing with divorce and separtion:

The Section on the Separation of a Family [is here explained] as follows: When the time comes to divide a fighting family, it is necessary to thoroughly investigate what the two sides did, and then decide suitably and honestly, according to the legal system. As an initial point, the mediator to a family dispute should do a thorough and honest investigation of the marriage arrangements and the root cause of the breakup. However, in actuality, if the husband is thrown out but he was innocent, the wife owes eighteen zho payable in three installments plus a sorry payment of clothes or ornaments and blankets [to the husband]. If the wife is thrown out but she is innocent, the husband owes twelve zho and three bre [measurement of grain] for every day and [three bre] for every night spent with him. In another system, he owes one gold se ba [money equivalent to seven bre] for the day wage and three bre for the night wage. [However,] these amounts should be determined according to the wealth of the family. (GDPB 12, lines 1095-1122).

However archaic or quaint the above lines may appear from our present day viewpoint, I think we could agree that the basic principle being followed by the Tibetan lawmakers of the past is one of fairness to both parties in a separation.

We do not have much literature on actual divorce cases in traditional Tibetan society but fortunately we have the published biography of Dorje Yudon Yuthok that provides the detailed account of a well known divorce that took place in 1928 between her father Surkhang Dzasa and her mother Lhagyari Tseten Chodzom. What is interesting in this case is that the male head of the family, Surkhang Dzasa, had to leave his family home and estate and even relinquish the family name of Surkhang.[24]

Only after the passage of the Hindu Marriage Act in 1955, eight years after India’s independence, could Hindu women obtain a legal divorce. Until 2018 Muslim men in India could legally divorce their wives merely by uttering the word “talaq,” (meaning divorce in Arabic) three times in person, over the phone or even in writing or a text message.

In 1925 the London newspaper of the Women’s Freedom League published a front-page interview[25] with a Tibetan women titled “Where Women Are Really Equal”. The women in question, Rinchen Lhamo, who was married to a retired English diplomat, may have allowed her yearning for her native homeland to somewhat color her memories, which in turn may have influenced the tone of the interview.

Nonetheless women in old Tibet certainly had more freedoms and rights than their counterparts in India, China and the rest of Asia, and perhaps even more than in Victorian England. Of course it would be wrong to claim that women in Tibet were equal to men in the full contemporary sense –– an equality that in spite of tremendous gains over the years, women in present-day democracies still strenuously contend they have not fully realized. It must also be mentioned that Rinchen Lhamo’s We Tibetans (1926) was the first book in English ever written by a Tibetan.

CONCLUSION

So how can we best describe the status of Tibetan women in their homeland without being overly romantic on the one hand or unduly cynical on the other? Alexandra David-Neel, the feminist crusader, adventurer and traveler attempted to answer this question in her article “Women in Tibet” (in Asia, 1934). She had travelled throughout Tibet in the 1920s when it was forbidden to foreigners, and had no illusions about the power and dominance of the Tibetan priesthood and the (male) ruling elite. David-Neel concluded that Tibetan women:

“… had achieved a de facto equality despite law and scripture unfavorable to them, this by virtue of innate independence and physical stamina…Tibetan women had mastered a harsh environment and gained sway over their men. Tibetan women were clever and brave and therefore valued by their husbands. It also helped that a large portion of the retail trade was in women’s hands.”[26]

Notes:

[1] Pietro Francesco Mele, Tibet, Snow Lion Publications, Ithaca, 1969, pg81

[2] Suydam Cutting, The Fire Ox and Other Years, Collins London, 1947, P 238

[3] Cutting p. 130.

[4] David MacDonald, Land of the Lamas, Seeley, Service & Co. Ltd., London 1929, p133.

[5]. Paul K.Nietupski, Labrang : A Tibetan Buddhist Monastery at the Crossroads of Four civilizations, Snow Lion Ithaca, 1999, Pg 45. 46

[6] Dr. Tsung-lien Shen & Shen-Chi Liu, Tibet and the Tibetans, Stanford Ca, 1952, p.143

[7] Amaury de Reincourt, Lost World Tibet: Key to Asia. Gollancz, London 1950. page 154-155.

[8] W.Tailing The Secret Tale of Tesur House: A Chronicle of Old Tibet, China Tibetology Publishing House, Beijing, 1998.

[9] Yudru Tsomu, “Guozhuang Trading Houses and Tibetan Middlemen in Dartsedo, the ‘Shanghai of Tibet’” Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review E-Journal No. 19 (June 2016) • (http://cross-currents.berkeley.edu/e-journal/issue-19) .

[10] Autobiography of Gompo Tashi Andrutsang, 35 photocopied pages of original typed document of the debriefing by CIA officer Roger McCarthy. A copy was kindly given to the author by Lisa Cathey, daughter of CIA officer Clay Cathey in 2008.

[11] Helga Uebach, “Ladies of the Tibetan Empire”, Women in Tibet, Janet Gyatso/Hann Havnevik (ed.) Hurst &Co., London 2005 p. 33

[12] Richardson & Snellgrove, A Cultural History of Tibet, Frederick Praeger, New York, 1968, p.60

[13] Helga Uebach, “Ladies of the Tibetan Empire”, Women in Tibet, Janet Gyatso/Hann Havnevik (ed.) Hurst &Co., London 2005 pp. 35-39.

[14] Their Highnesses Chögyal Thutob Namgyal and Queen Yeshi Dolma of Sikkim, Hbras ljong rgyal rabs (The History of Sikkim), The Tsuklakhang Trust, Gangtok, Sikkim, 2003 (compiled in 1908).

[15] John Claude White, Sikhim & Bhutan: Twenty-one Years on the North-East Frontier, 1887-1908, Longmans, New York, 1909, p. 23.

[16] “Joint Statement of Lobsang Wangmo and Rinzin”, Tibet Under Chinese Communist Rule, Information and Publicity Office of His Holiness the Dalai Lama, Dharamshala, 1976, p.57

[17] Tseten Yangki, interview with the author, 1984 Dharamshala.

[18] Edgar Snow, Red Star Over China, Penguin Books, 1972, p. 235.

[19] Melvyn C. Goldstein, Ben Jiao, & Tanzin Lhundrup, On the Cultural Revolution in Tibet: The Nyemo Incident of 1969, University of California Press, Berkeley, 2009, p. 4.

[20] Hanna Havnevik, “The Role of Nuns in Contemporary Tibet”, Barnett & Aikiner (eds) Resistance and Reform in Tibet, Hurst, London, 1994, p. 265.

[21] nycyak “Tibetan women: Trinley Chodon & the Nyemo Revolt” April 4, 2012, Lhakar Diaries, https://lhakardiaries.com/2012/04/04/tibetan-women-trinley-chodon-the-nyemo-revolt/

[22] B. J. Gould, The Jewel in the Lotus, Chatto & Windus, London, 1957, p.236.

[23] Rebecca R. French, “Tibetan Legal Literature: The Law Codes of the dGa’ ldan pho brang”, The Tibetan and Himalayn Library, https://bit.ly/39ZfKNl

[24] Dorje Yudon Yuthok, House of the Turquoise Roof, Snow Lion, Ithaca NY, 1990 pp. 43-46

[25] Tim Chamberlain, “Edge of Empires”, British Museum Magazine No 66 Spring-Summer 2010 pp 50-52.

[26] Barbara Foster and Michael Foster, The Secret Lives of Alexandra David-Neel, Overlook Books, 2002

Excellent article, enjoyed reading it. Thanks

I enjoyed reading this article thoroughly. Thank you Jamyang la!