TIPA’s project in the 1980s to seek out, research and document authentic folk songs, dances, and other performing traditions of Tibet.

By Jamyang Norbu

In the summer of 1959, a small group of Tibetan musicians in Kalimpong were summoned to Mussoorie by the just established exile government. This group was instructed to organize a performing group in Kalimpong to publicize the Tibetan issue. A troupe was formed that gave its premier public performance on August 11, 1959 at the Kalimpong town hall. The troupe also performed at the Afro-Asian Conference in Delhi on April 1960 before the President of India and other dignitaries. In 1961 this troupe moved to Dharamshala where it was joined by younger recruits from the Tibetan Nursery and other refugee schools, and became known in Tibetan as the Dhoegar Tsokpa, and by a number of different names in English over the years. In 1981 it was renamed the Tibetan Institute of Performing Arts (TIPA), when I became director.

Although a number of the original members were skilled musicians and performers, their first aim was to put on colorful shows to keep up the morale of the refugee community while entertaining and informing foreign and Indian visitors. TIPA was not founded with the goal of researching, preserving or documenting Tibetan performing traditions. Over time the different dances and songs from different districts and regions blended into generic performances where provenance and authenticity were largely lost. Furthermore, new and politically charged lyrics were added to traditional songs.

Nonetheless, sporadic attempts were made –– over the years –– by certain TIPA directors to research and perform authentic song and dance traditions. Starting from 1981, a systematic project was established to seek out, research and document different song and dance traditions from all over Tibet and archive each tradition through interviews, tape recordings, videos, photographs. These findings would be subsequently passed on to TIPA performers and students. In this new project authenticity was the watchword. Brief scholarly introductions would often be given before a recital where the origins, source and history of the performance was relayed to the audience.

This paper presents the background to TIPA’s endeavor to establish cultural authenticity in their artistic performances and furthermore preserve through photographs, documentation, recordings, videos, interviews etc., all aspects of Tibet’s ancient and diverse performing traditions.

THE UNDERLYING PROBLEM

The first struggle that Tibetan performance culture faced in exile was of finding a framework in which to represent itself in the modern world. For about a decade (from roughly 1951 to 1959) Tibetans had been influenced by the propaganda performing units of the Chinese Communist Party. One of Red China’s warmest admirers, Edgar Snow, has explained the importance of these organizations: “There was no more powerful weapon of propaganda in the Communist movement than the Red’s dramatic troupes, and none more subtly manipulated.” These Chinese performances were very effective in Tibet, leaving a lasting impact on Tibetan performers and creators.

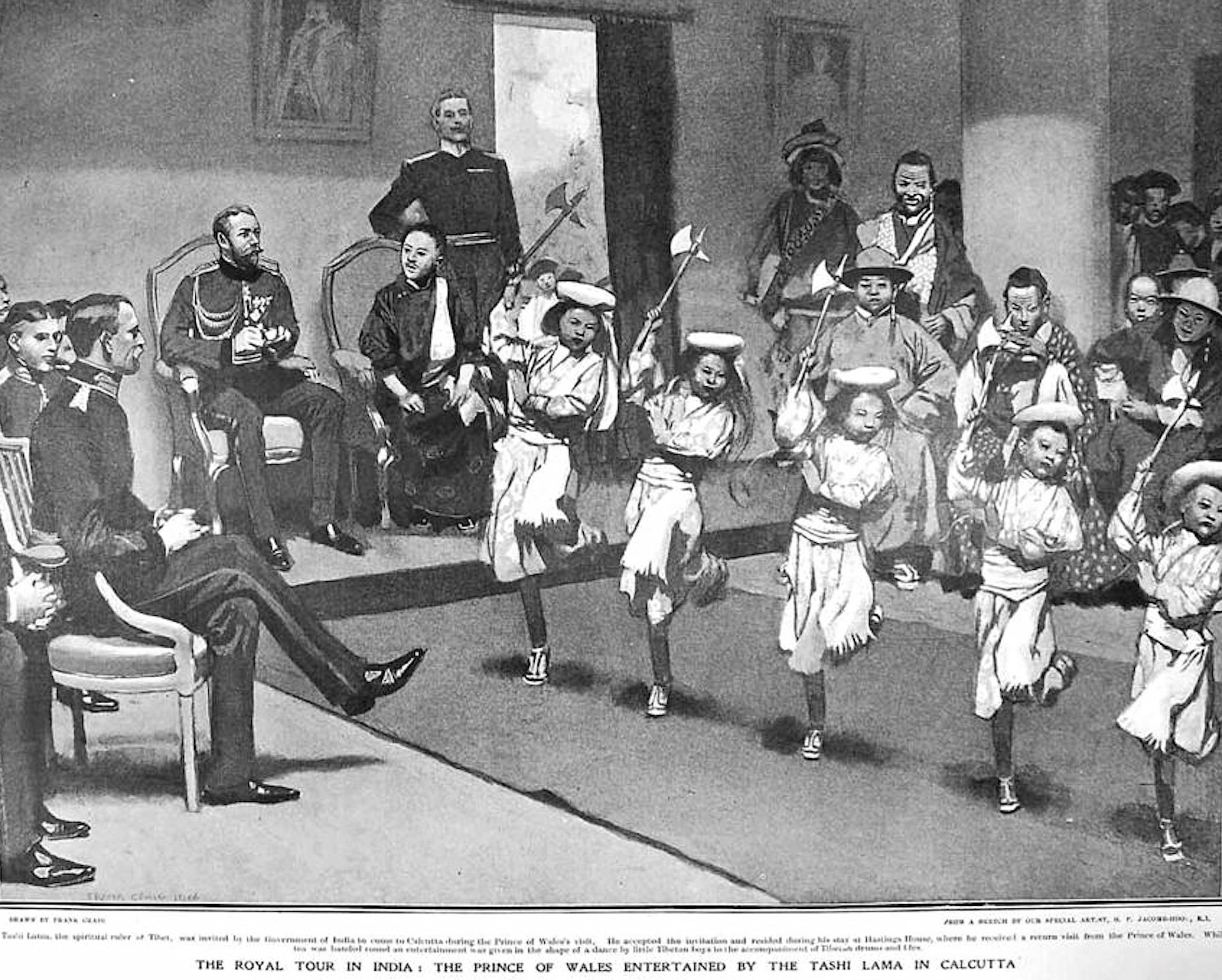

One such performing troupe (and school) set up in the Tibetan capital was called the Bhojong Dhoegar Tsokpa, which has been translated by some scholars as “Tibet Song-and-Dance ensemble.” In this organization Tibetan dances, songs and various performing traditions from different villages and districts were brought together and reconstituted to serve the propaganda requirements of the Chinese Communist Party. Because of the novelty of the electrically lit proscenium stage, western musical instruments, and flamboyant dances with flashy acrobatic turns, the performances became popular with Tibetans, particularly the younger generation. Among the musicians and dancers trained at the Bhojong Dhoegar Tsokpa, a couple became members of the exile-performing troupe at Dharamshala.

In Dharamshala the exile performing troupe was, according to the Irish travel writer Dervla Murphy “… called somewhat formidably The Tibetan Refugees’ Cultural Association Drama Party.” The troupe was not tasked with the duty of preserving authentic Tibetan performing culture but rather with providing performances that would provide Tibetan refugees with a sense of cultural and political unity and demonstrate to visiting foreign visitors and the Indian public the unique nature of the Tibetan people and culture. To serve this purpose “historical/musical plays” were written by Trijang Rinpoche and Dudjom Rinpoche where glorious episodes in Tibetan history were enacted. These plays were interspersed with colorful dances and songs.

Many old folk songs were now re-written with politicized and patriotic lyrics: Rangshung Chinzé (Cherish Your Own Government), Cholsum Chigdril Nyamshay (Three Provinces Unity Song), Toepay Luyang (Song in Praise of the Dalai Lama), Mimang Langlu (People’s Uprising Song), Mangtso Sarshay (New Democracy Song), Punda Chigdril (Unity and Brotherhood) among others. On a more socialist note, we had Zo-Zhing-Drok Sum or (“Dance of the Worker, Farmer and Nomad Trio).

It should be pointed out that the propagandistic gloss never fully overwhelmed the cultural feeling and Tibetan-ness of the performances. Dervla Murphy, who attended a few performances at Dhoegar Tsokpa, and noted the underlying propaganda, nonetheless enjoyed the shows immensely. “We soon realized that we were seeing folk-art of a quality now extinct in Europe. These performances are a palpable extension of the spiritual and emotional life of the audience.”[1]

In

the following years some sporadic efforts were made at TIPA to collect and

preserve authentic Tibetan music and dance, but since the Institute also had to

constantly perform its standard programs to entertain Tibetan audiences, not

only in Dharamshala but also at schools and settlements all over India, not

much time could be devoted to these efforts. Furthermore, TIPA was also

required to perform propaganda plays (tib. tamchoe)

depicting Chinese atrocities and the heroism of Tibetan resistance fighters.

TIPA also had to provide a full Western- style military band for the March 10th

ceremonies and other such official functions of the exile government. All this

took up most of the time and energy of the Institute, not counting time spent

in providing the younger members with a daily education in Tibetan language as

well as English and Hindi.

PRESERVATION OF THE NANGMA/TÖ-SHAY TRADITION

One of the first conscious and most successful acts of music preservation at TIPA was in the preservation and passing down of the light classical Nangma and Tö-shay musical traditions of Lhasa. This initiative was consciously taken by the pioneering group at Kalimpong whose members, to ensure the propitious future of this musical tradition, played the tune Talashibay or “Good Fortune” at their first recital and made an offering of Tibetan tea and auspicious rice dessert (dre-sil) to all.

Nearly all the early musicians at TIPA were from Lhasa –– Nornang Ngawang Norbu, Maja Ngawang Thutop, Chija Tashi Dorje, Jhola Dorje Rigzin, Bhartso Thondup Dorje, Jhola Lhawang Tsering, Jhitiling Ngawang Dhakpa, Gyen Lutsa and some others were skilled and devoted instrumentalists in the Nangma/Tö-shay tradition. Through their efforts practically all the melodies and lyrics of this musical tradition were collected and preserved. Incidentally the use of the Sino/Japanese numerical notation (phutsi) in the fifties also helped in this task. Along with the music, the dance accompaniments were also preserved and performed. A long-lived and important musician and instructor in this successful preservation effort was Gyen Lutsa-la, a professional Lhasa musician who passed away at TIPA in 1984.

OTHER PRESERVATION EFFORTS BEFORE 1981.

Over the years, quite a number of the directors and performers at the Institute felt the need to seek and preserve authentic and unique expressions of Tibetan performing culture and not just mix them all up in a generic program of so-called folk dances.

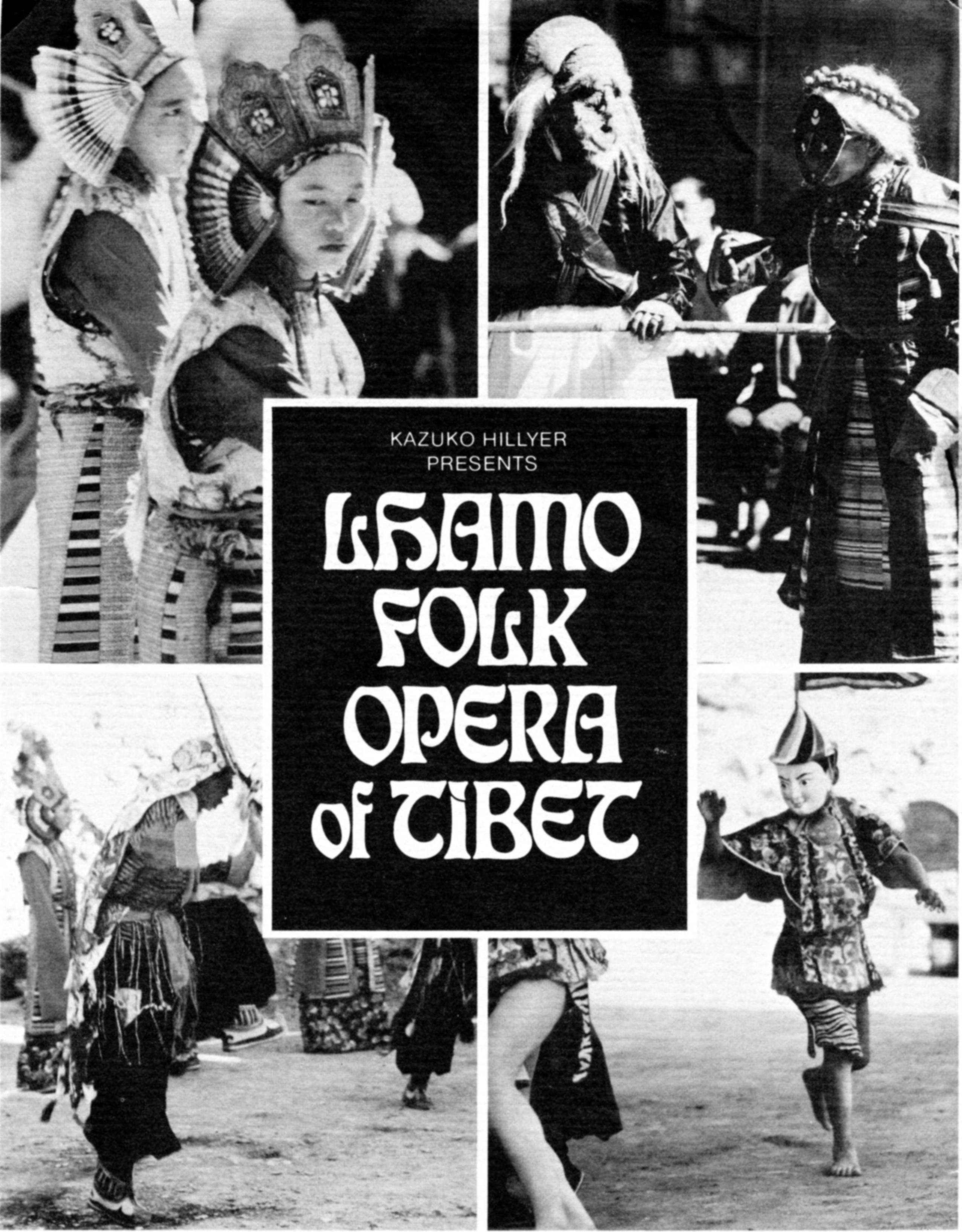

During the directorship of Phuntsok Namgyal Dumkhang (1966-68) the initiative was taken to introduce the Ache Lhamo Opera at TIPA. Earlier only excerpts such as the dance of the wild yaks had been performed in variety shows (shay-na). The Kyormolunga opera master Norbu Tsering was invited from Kalimpong and soon two plays, Sukyi Nyima and Dowa Sangmo were being performed with great success. Dumkhang also managed to incorporate authentic folk songs and dances as Pema Thang (Lotus Fields) from Kongpo and the song Rinzin Wangmo (both taught by Norbu Tsering) and Ney Sarpa (The Dance of the Pilgrims), into TIPA’s repertory.

In 1969 the general secretary of TIPA, Tenzin Gyeche Tethong, started an annual competition –– with prizes–– between the two “houses” at TIPA for new performances, that encouraged each group to seek out fresh folk songs and dances from different refugee communities in and around Dharamshala. These were performed on TIPA’s Founding Day, and later incorporated into regular TIPA performances.

FINDING A CONSERVATION MODEL IN THE USA

I first taught at TIPA in 1969 and 1970, but in 1974-75 I was asked to be the manager of TIPA’s first international tour (organized and sponsored by New York based impresario, Kazuko Hillyer International). Following a performance at the Smithsonian Institute at Washington DC, TIPA director Ngawang Dhakpa-la and I were taken by a Smithsonian official to its Bureau of American Ethnology and shown the collection of recordings of Native American music and culture preserved in photographs and wax cylinder recordings. The official advised us that Tibetans should also make the effort to preserve and document their musical culture in a systematic manner before it was lost. The official gave me some literature on this project along with a vinyl recording of Native American songs.

I also visited the Library of Congress’s Archive of American Folk Songs that housed thousands of field recordings of folk music, spirituals and early Blues recorded and collected by the ethnomusicologist Alan Lomax and others. Like many schoolboys in the sixties, I had been a fan of American folk music (Peter Paul & Mary, Joan Baez, Bob Dylan, etc.) and it was a revelation for me to learn how much American music owed to the early preservation work done by Lomax and others. I also obtained literature and vinyl records of these and other collections.

So, when I was appointed director of TIPA in January of 1981, I had some idea of the cultural direction the Institute should take. During an audience with the Dalai Lama later that year I tried to convey to him my scheme to collect and document authentic folk songs, dances, and other performing traditions of Tibet, and weed out the more propagandistic lyrics in the songs and performances. His Holiness expressed his support for this new direction in TIPA’s work and also jokingly commented that he was not Chairman Mao and did not need all those songs of praise.

GAR: COURT DANCE AND MUSIC TRADITION OF TIBET

My first project at TIPA was the revival of the Gar – the Court Dance and Musical tradition of Tibet. Earlier a brief Gar dance performance had been included in a historical play, when the Tibetan emperor Ralpachen entered the stage. The Gar tradition not only included a variety of dances, but also many songs (gar-lu) and also instrumental pieces performed on an extensive variety of exotic instruments. The principal Gar instruments were a pair of kettledrums (damma) and double-reed oboes (sunna). To get an idea of the extensive and even unusual variety of instruments check out my article on this subject in the commemorative book for the 25th Anniversary of TIPA.[2]

Jhola Dorje Rigzin-la a former Gar performer from Lhasa, and former TIPA instructor, was recalled from retirement to teach the Gar music and dances to TIPA senior students and children. Within a year we were able to arrange the first Gar performance for the Dalai Lama and the Tibetan public on the morning of the Tibetan New Year Losar in 1982, at the Tsuglakhang temple at McLeod Ganj.

In 1983 a separate Cultural School was started at TIPA (with the financial help of Mrs. Anne Jennings Brown of UK) exclusively to train children from the age of six to fourteen to be Gar dancers, and also receive training in Tibetan classical music. An initial group of nineteen children were recruited from various settlements and schools in India and Nepal and looked after by a matron. They received their regular education at TCV school but trained in dance and music an extra two hours every weekday and a full day on Saturday.

A former Gar master (garpon) from Lhasa, Pasang Dhondup, also helped train the dancers and the musicians. Under Pasang Dhondup’s tutelage many Gar tunes were taught to TIPA musicians and also recorded. A research project was initiated that was advised and guided by Tashi Tsering-la (senior researcher for the Library of Tibetan Works and Archives, LTWA) who also let TIPA have a copy of the 17th century treatise on Gar compiled by the 5th Dalai Lama’s Prime Minister Desi Sangay Gyatso. A field research trip was undertaken by Pasang Dhondup and Tashi Dhondup (senior instructor) to Ladakh where the Gar tradition is said to have originated.

OTHER RESEARCH & PRESERVATION INITIATIVES

With the successful preservation and performance of the Gar music and dance tradition, we concluded that TIPA that we should continue to seek out and record and preserve other unique performing traditions of Tibet, surviving in exile communities in India, Bhutan and Nepal.

All staff and students at TIPA had an annual two-month winter break. I encouraged our senior performers and instructors to use that period to conduct independent research projects on any music or performing tradition that he or she might have heard about or discovered. TIPA administration would provide travel and other expenses, and loan them the necessary cameras and tape recorders. A cash bonus would also be given to the researcher. Tashi Tsering-la provided these aspiring researchers with a short course on research methodology and the project was launched.

PORONG GYALSHAY: THE VICTORY SONG OF PORONG

The first fruit of the research initiative came from the Porong refugee community in Kathmandu who were kind enough to provide TIPA researchers information and instructions on an important historical and dance tradition from the Porong district in Tibet.

The Gyalshay (rgyal-gzhas) or Victory Song of Porong, the royal song and dance of Porong, is an ancient tradition performed by the men and women of Porong Township in southwestern Tibet on the Nepal Tibet border. In earlier times Porong district had been governed by the Porong Jhepon, the Lord of Porong, whose family had ruled this area for centuries.

The performance is a daylong one, broken up in specific stages concluding with a mock sacrifice (pre-Buddhist?) of a sheep. Generally the dance is performed by about forty dancers –– half women and half men. The men’s costume is martial in inspiration consisting of an enormous, fringed headdress and also riding-chaps (peeshup), matching bow and arrow cases (da-zhu sakdar), wrist-guards, and whips. The women carry the da-dhar or the mystical arrow, wrapped in five colored ribbons. The musical accompaniment to the performance is a large drum carried and beaten by one drummer wearing a yellow bokto hat.

The Porongwa claim that this dance was first performed by the nobles and ladies of Songtsen Gampo’s court to welcome the Chinese princess Wencheng to Lhasa. A video recording was made of the Gyalshay at the Pelmo Choding monastery at Porong and filmed by Charles Ramble and Martino Nicoletti. Entitled “The Victory Song of Porong: The Royal Music of Porong”, the recording is available at the Tibetan and Himalayan Library website.[3]

LINGDRO DECHEN ROLMO: SACRED DANCE OF KING GESAR

The next performing tradition was located by researcher/scholar Tashi Tsering-la of the Library of Tibetan Works & Archives at the Phuntsokling Tibetan settlement at Orissa. Senior TIPA artiste Tashi Thundup travelled to this settlement and was subsequently taught the Lingdro tradition by the old exponent Tagsar Norsang and his daughter Yangzom.

This magnificent dance tradition is to honor the Tibetan epic hero Ling Gesar. A more detailed account of the Lingdro is given in the website of the Ripa Ladrang Foundation. “This sacred dance is known by the name of ‘Lingdro-Dechen-Rolmo’ meaning the Dance of Ling, Music of Great Bliss’. There are five chapters that originated from the pure vision of treasure-teachings of the great Jamgon Mipham Rinpoche (1846-1912), who recognized King Gesar as the “Assemblage of the Three Roots” and king of the Dharma protector Drala Werma. Lingdro is one of the vital parts among numerous cycles of teaching and Sadhana practices of Mipham Rinpoche.”[4] The Reting Regent who was a great Lingdro enthusiast is said to have increased the performance to twelve chapters.

Though the performance of the Lingdro is regarded as a spiritual practice, it is performed by the laity –– men and women. It was successfully performed by TIPA on the Dalai Lama’s birthday (I am not sure of the year) and on a number of other occasions and places for the Tibetan public. The Lingdro performance appears to be preserved at Orissa, as well as in Nepal and elsewhere. Attached are links to two performances of the dance: one at the inauguration of the Orissa Monastery[5] and the other at the Kagyu Monlam Stage in Bodhgaya.[6] Some time ago I saw a Youtube video of a Lingdro performance in Ladakh, but unfortunately I am unable to locate the video anymore.

DHRO-DUNG DRUM DANCE

That same year senior TIPA artiste Karma Gyaltsen and Tenzing Gonpo (?) conducted research into the Dhro-dung drum dance tradition. This dance is performed by a dozen or so dancers adorned with the five color scarves (dhartson nenga) and with quoit-shaped headdresses (agor). They have a single drum tied under their left armpit that they beat with two curved drumsticks in either hand. They are led by a masked character carrying a dathar arrow in one hand and the archer’s thumb-ring (tegor) in the other.

This masked character is said to represent the legendary trickster Agu Tonpa[7]. Agu Tonpa is said to have borrowed wheat grain or ghro from a wealthy farmer to help people in distress but was unable to repay the debt. He gathered the people who had received grain from him and taught them the drum dance, which they performed before the rich farmer’s house. Agu Tonpa then declared that with this Dhro (Bhro)dance he had repaid the borrowed Dhro (ghro) grain –– both words being pronounced the same though spelled differently. Hence the dance is called the Dhro-dung, as the word dung means to beat, and Agu Tonpa had beaten the farmer on the head (go-dung) ––the expression also meaning to trick or swindle.

Earlier a short drum dance sequence had been performed as an item in one of the variety performances, but now thanks to the efforts of these researchers two distinct traditions were discovered and subsequently performed for the public. The first tradition was the Serma Dhro-dung from Tsang and performed by the me-ser farmers under the Tashi Lhunpo monastery. The other was the Dhol-Dhrodung of the Lhoka area. These two traditions though involving the beating of drums under the armpit of the drummers, had different dance steps and choreography and also song lyrics. The latter also had a sequence where the drummers would twirl their long pigtails that were weighted at the tip.

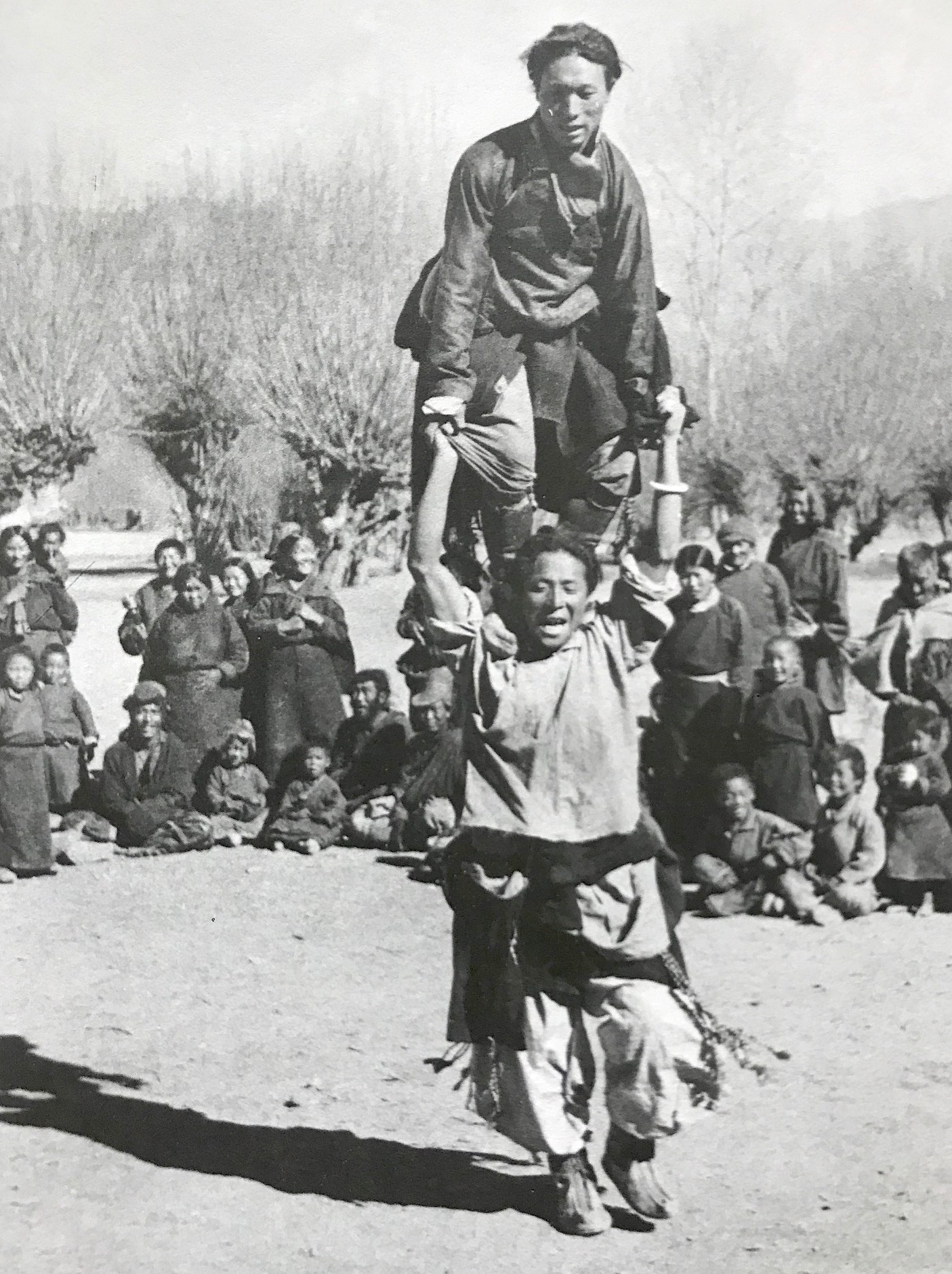

REPA: ACROBATIC DANCE AND DRAMA PERFORMERS OF KHAM

A concerted effort was made at TIPA in 1983 for reviving the Repa acrobatic dance tradition (sometimes called the Tibetan “gypsy” dance) which had till then been just a five-minute item in a TIPA variety dance program.

In Tsawarong, Pagshod and Dragyab in Eastern Tibet roving bands of dancers called Repa or “cotton clad yogis” performed acrobatic dances and plays. In their kha-bshad or narration which is delivered by the res-gyen (or elder repa), who plays a Shang, the Bhönpo flat bell, and describes their tradition as being founded by Rechungpa, the favorite disciple of Milarepa. One of the plays (trab-zhung) performed by the Repa is the well-known episode from the Mila Gurbum called “Rechung’s Journey to Central Tibet”, or Rechung Ü pheb”, though I have been told by the scholar Tashi Tsering-la that this was not the case. The elder Repa trades banter with the women Repas or Resa-ma, who all carry handled drums which they beat, and twirl around them in a graceful and agile manner.

Our researcher was able to locate Thupten-la, a former member of the Repa community, living in Delhi, but he told us he had not been a performer and was unable to teach us the dances. But he provided us with the lyrics of the songs and recitations of the regyen dancers. We were more successful in locating a female Repa dancer (Resama) in Dharmshala who was incidentally a member of the Dalai Lama’s security team. Aja Kalsang Tsomo taught our female dancers the very difficult dance sequences with handled drums, which required much skill, agility and grace.

We now had the basic dance moves for the male and female dancers. But did not know the many complex acrobatic dances and moves performed by the male Repas. Fortunately, we were able to borrow a 16mm film of a documentary made by members of the OSS mission to Tibet in 1942.[8] The film had a significant amount of footage of the acrobatic performance of the Repa dancers. TIPA artists spent much time watching the film again and again and managed to master the acrobatic movements and dance sequences of the Repas. We were able to provide the Dharamshala public a full performance of this dance routine.

BA-SHAY SONGS AND DHRO DANCES of KHAM

All Khampa style dances at TIPA prior to 1981 had been the generic Dhoegar dances performed in Khampa costume but not derived from any specific Khampa dance tradition. We attempted to introduce the Dhro dance tradition of Kham to TIPA’s repertory in 1984. TIPA actually had a skilled Dhro dancer, Drayab Jampa Lungtok (aka Chonze-la), in residence for many years, but he had not had the opportunity to teach his particular skill set because of the continued usage of generic dances at TIPA dance presentations. Chonze-la was relegated to performing in operas and in plays, and he was very good at them.

We then decided we had to have an exclusive program of Khampa Dhro dances –– with the show stretching for many hours, as was the tradition in Eastern Tibet. The dances are always performed in a slow and majestic manner (jhing-jhakpo) and only at the concluding segment does the performance become fast and energetic. (Most videos of dances from Eastern Tibet these days only feature the fast sections). The songs we had for this dance performance were generically called Ba-shay or songs from Bathang, and the instrument used for them was the Piwang, or two stringed fiddle. Traditionally horsehair was used for the strings as well as the bow hair, but we had to settle for nylon violin strings and nylon bow hair.

The Khampa piwang fiddle employs a very different playing technique to that of the Lhasa orchestral fiddle. With the Khampa instrument a constant staccato rhythm is maintained, through which the melody is inter-woven. This technique was taught to our musicians by a visiting Khampa fiddler. Also, the small sound box of the normal fiddle used in the nangma orchestra was too small and like the Chinese (proto-Mongolic instrument) huqin.[9] So we had to make new instruments with larger sound boxes. We experimented using half an Indian dhol drum for the sound box and managed to get a much louder sound with a lower register.

A debut performance was given on the Dalai Lama’s birthday in 1984, with three fiddlers and thirty dancers, men and women, all dressed in voluminous Khampa robes, ornaments, accessories and headdresses.

DEKAR SAMPHE DHONDUP: WHITE SEED FULLFILLER OF WISHES.

One of the most popular recitative and chant traditions in Tibet (always performed by a single vagabond minstrel) is that of the Dekar Samphe Dhondup or “White Seed Fulfiller of Wishes” (according to one interpretation). This personality is considered to bring good luck and is a necessary adjunct to wedding ceremonies and the like. The Dekar’s presence is especially required in the early morning of the Tibetan New Year, where he recites a long litany of auspicious and “Good Fortune Conveying” verses (tashi-chey) and is rewarded with food and drink and cash from all the household he visits.

Charles Bell says that though “poorly housed and clad” the Dekar makes people laugh by his absurdities. “I have arrived, he will say, from a far-distant country, where I visited one of the mansions of the Lord Buddha and come now to bring blessing to you all.” His grandiose recitations fall into a few categories. There is the deshay or description where he gives a full run-down on the virtues of his staff, his begging bowl, his goatskin mask and his sogchil earring, in the most grandiose and absurd of terms.

He also recites the “Origin Chronicles of Tibet” “Bhod sipa chakapa chagrap, where short pithy verses on how Lhasa, Samye, Chamdo, Drepung and other important cities and places in Tibet came into being. He also recites his own distinguished family history, concluding with the story of how he ended up as a luckless beggar-boy (trang-trug-sothey-maypa) forced to roam the world. The recitations are never monotonous, and constantly vary in style, tonality and rhythm and is “poured out in a stream of extravagant language, interlarded with jests which cannot be said to border on the vulgar, for they are well over it.”[10]

In exile there were vague reports of a Dekar exponent or two, in Darjeeling and even in Dharamshala, in the early sixties, but at TIPA we were unable to contact one, or obtain any transcripts or recordings of the recitations. Also no older person, even someone from Lhasa, could recall or properly recite any of the verses, like they might recall song lyrics, because of the technical difficulties of the recitation style. Eventually, entirely by good luck an old tape spool was discovered in a TIPA office cupboard where an entire hour-long performance of a Drekar was recorded when that person came to Dharamshala in the early sixties. Unfortunately, there was no mention or record of his name or provenance, or who had made the recording.

A few senior artists immediately began the task of transcribing the tape and also of committing the entire recitation to memory. The discovery of the tape was providential, as our next Ache Lhamo play, Nangsa Wöbum, required a Dekar recital at the wedding of the maiden Nangsa to the Prince Dhakpa Samdup of Rinang. A few of the senior artistes, Tashi Thondup, Lhakpa Tsering and another student also visited a number of households in Dharamshala early in the morning of the 1982/83 Losar. These Dekar performers were, of course, entirely unexpected, but very welcome. Ever since then this tradition has been actively maintained by artistes in Dharamshala and elsewhere. I have been informed that at Losar ceremonies in New York City, Minnesota, Toronto and even Zurich there have been Dekar performances.

FORD FOUNDATION TRAINING PROGRAM

In order to be able to spread the work of cultural preservation to Tibetan exile communities and schools in India, Bhutan, Nepal and abroad, we embarked on a program to train Performing Arts instructors. The Ford Foundation in New Delhi provided us a generous grant for a two-year training program. The project was headed by assistant director, Phurbu Tsering, who prepared a detailed curriculum and rigorous training schedule, so that the program could be successfully completed within the time frame. Twenty young and qualified candidates were recruited from various Tibetan schools and institutes. They received intense training in the playing of various musical instruments and learning songs, dances, operas etc., and it required the students to study and practice well into the night to achieve the required artistic standards that we demanded. Besides the new trainees all other artistes at TIPA were given their own musical instruments and required to complete the curriculum.

The trainees were also given a course in research and documentation and encouraged to try and find undiscovered songs and performing traditions in the communities where they would be serving. Quite a number of these trainees later uncovered new material and new musical traditions that they brought back to TIPA.

One trainee, Ngawang Choephel, after graduating from TIPA, studied ethnomusicology at Middlebury College in Vermont. He then went to Tibet in August 1995 to record and video Tibetan folk songs and performances. Unfortunately, in September 1995 he was arrested by Chinese State Security (gongan) and charged with “espionage and counter-revolutionary activities” He was sentenced to 18 years of imprisonment without a trial and without any evidence to support the charges against him.

A highly publicized campaign that began with his mother’s solitary protests received international attention and support. Finally, Ngawang Chophel was released in 2002 on “medical parole” from Chengdu prison after six years imprisonment. He put together what videos and material he had managed to salvage and in 2010 came out with a documentary film Tibet in Song. It won the World Cinema Special Jury Prize in the Sundance Film Festival and also the Cinema For Peace International Human Rights Award.

MAKING TRADITIONAL MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS.

Before 1981, TIPA only had a few musical instruments for the entire Institute: three or four dranyens, a few fiddles of Chinese make, a couple of hammer dulcimers and an opera drum made from a large, hollowed-out log. The Ford Foundation grant provided us with enough funds to provide each of the trainees with the necessary musical instruments. It further allowed us to employ the needed craftsmen and set up a dedicated workshop so that a permanent source of musical instruments would be available. We were fortunate to acquire the services of professional dranyen maker, Oo Tsundru-la from Western Tibet. He was assisted by Kunga-la (who still makes dranyens in Dharamshala) and very soon we were able to provide every performer and student at TIPA (including the Cultural School children) a dranyen each. We also managed to contact an Indian instrument manufacturer in Delhi, who made the santur (hammer dulcimer) of Kashmir. Only a few modifications were required to produce the Tibetan dulcimers and soon this firm was able to provide us with over fifty instruments. We also made our own fiddles, of many sizes and tones.

Unfortunately, we were not able to find a Tibetan drum-maker for a long time. Even the Dalai Lama’s Namgyal monastery was using Indian military snare drums (the sides covered with maroon fabric) for their ritual music. The sharp staccato sound of these snare drums was tonally unsuitable for Tibetan music, both secular and spiritual. One day the Kashag minister kungo Tsewang Tamdin contacted me and asked me if I needed the services of a traditional drum-maker. The minister had earlier been the manager of Sakya monastery in Tibet and knew a Sakya drum-maker who had once made drums for the Sakya monastery. He put me in touch with this person (whose name I cannot recall) who was more than happy to join the TIPA instrument-making department. This man was a real professional who made perfectly shaped traditional wooden drums –– with the required deep booming sound –– on a near assembly line basis. The master painter Chenmo Jampa Tseten la of Lhasa decorated the sides of the drums with beautiful and elaborate dragon designs.

Earlier TIPA employed a couple of tailors for making costumes. Now a full-fledged costume department was created with a dozen tailors and seamstresses working under the tutelage of master costume-maker Gyen Chime Dorje to make elaborate traditional costumes, ornaments, jewelry, masks, and various props for the performances.

TEMPLE OF THE PERFORMING ARTS

We also built a ‘Temple of the Performing Arts’ with statues of Buddhist deities, saints and lamas related to the performing arts: Sarasvati (the Indian goddess of the arts), Padmasambhava (tantric dance), Milarepa (singing and composition), Sakya Pandita (treatise on music), and the Sixth Dalai Lama (romantic songs). Of course, we also had an image of the Buddha and the Bodhisattva Manjusri. The centerpiece was a large statute of Thangtong Gyalpo.

All these images were housed in a detailed three-dimensional representation of the Tibetan landscape featuring mountains, wilderness, pastoral and agricultural scenes. The Potala palace, a monastery, a town, a merchant caravan, the Tsangpo River and a chain suspension bridge provided detail and specificity to this miniature Tibetan world. Tiny models of every conceivable Tibetan animal, real and mythical, were present in this representation. One of the intentions of this temple was to provide younger TIPA members with a detailed and enchanting vision of their lost homeland. The concept and design was mine but the actual execution of the project was undertaken by TIPA’s master sculptor (jimsok chenmo) and mask-maker, Oo Kalsang Thundup of Kongpo.

The ‘Temple of the Performing Arts’ attracted many visitors and worshippers, in its own right.

DOCUMENTATION AND ARCHIVES

At TIPA we set up the beginnings of a proper archive by systematically cataloging the audio tapes, videos, photographs, documents, reports and other material obtained by various researchers, and deposited them in one location at the TIPA administrative office. We had also recorded a number of Lama Mani recitations, particularly of Ache Lhamo stories as Pema Wöbar, Nangsa Wöbum, Suki Niyma and so on, for our artistes to study, and also interviews with traditional artistes and experts from pre-1959 Tibet as the opera master Norbu Tsering, the Gyalkarwa Lhamo expert Chagdam Ugen, The Chungba opera master Dorje la, Gyen Phusam la the Lhasa opera performer related to the famous Gegen Tashi of the Kyormulung company, former foreign minister Liushar Thupten Tharpa, a Lhamo expert and others.

In these archives we also had copies of the song lyrics of the Drebuling tradition that had been lost in exile but had earlier been performed on the second day of the Tibetan New Year for the Dalai Lama at the Potala Palace. Hugh Richardson had been intrigued by this unique musical tradition when he heard it in Lhasa and had requested the Potala secretariat for copies of their songs. Mr. Richardson later donated these papers to TIPA. We also established the core of a future “Museum of Tibetan Performing Culture”, with old costumes, jewelry, antique musical instruments, and many authentic artifacts donated to TIPA by the Dalai Lama and other patrons, and also purchased by us over the years.

TIPA administration also published a newsletter/magazine DRANYEN or “melodious sound” to inform our friends and sponsors about our activities and also publish articles on different aspects of Tibetan musical and theatrical tradition

Before concluding I should mention that in this study I have not included the Ache Lhamo Opera tradition that TIPA successfully resurrected in exile, since I had already written a substantial article on the subject in 2015. For those interested check out Lungta: Journal of Tibetan History and Culture.[11].https://rb.gy/atapz

Notes:

[1] Dervla Murphy, Tibetan Foothold, Eland Publishing Ltd; Reprint edition (2011-10-15)

[2] Jamyang Norbu, “A preliminary Study of Gar; the Court Dance and Music of Tibet, Jamyang Norbu (ed), Dzlos-gar, Library of Tibetan Works and Archives, Dharamsala, 1986.

[3] https://audio-video.shanti.virginia.edu/video/victory-song-purang-royal-music-purang-01

[4] https://www.ripaladrang.org/lingdro-dance/

[5] Performance of a Lingdro Dance at the Orissa Monastery Grand Opening

[6] Lingdro – Sacred Dance of King Gesar

[7] Rinjing Dorje, (retold and translated by) The Tales of Aku Tompa: The Legendary Rascal of Tibet. Second Edition. Barrytown, NY: Station Hill Arts, Institute for Publishing Arts, Inc. 1997.

[8] Inside Tibet OSS Mission to Tibet, 16mm 1942 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nQp6GXSF89c

[9] The name Huqin literally means “instrument of the Hu peoples“, suggesting that the instrument may have originated from regions to the north or west of China generally inhabited by nomadic people on the extremities of the Chinese empire.

[10] Charles Bell, The People of Tibet, Oxford, 1928.

[11] Jamyang Norbu, “The Wandering Goddess: Sustaining the spirit of Ache Lhamo in the Exile Tibetan capital,” Lungta No 15, The Singing Mask, Echoes of Tibetan Opera, guest editor, Isabelle Henrion-Dourcy, editor Tashi Tsering. 2015. https://rb.gy/atapz

I remember those days. I was in Dharamsala. You really transformed the TIPA from a boy to a man. One of your best and well-known legacy or contribution to the Exile-Tibetan Society. Keep up all the good work. Thank you.