PHOTOGRAPHY AND TIBET by Clare Harris, Reaktion Books (2016)

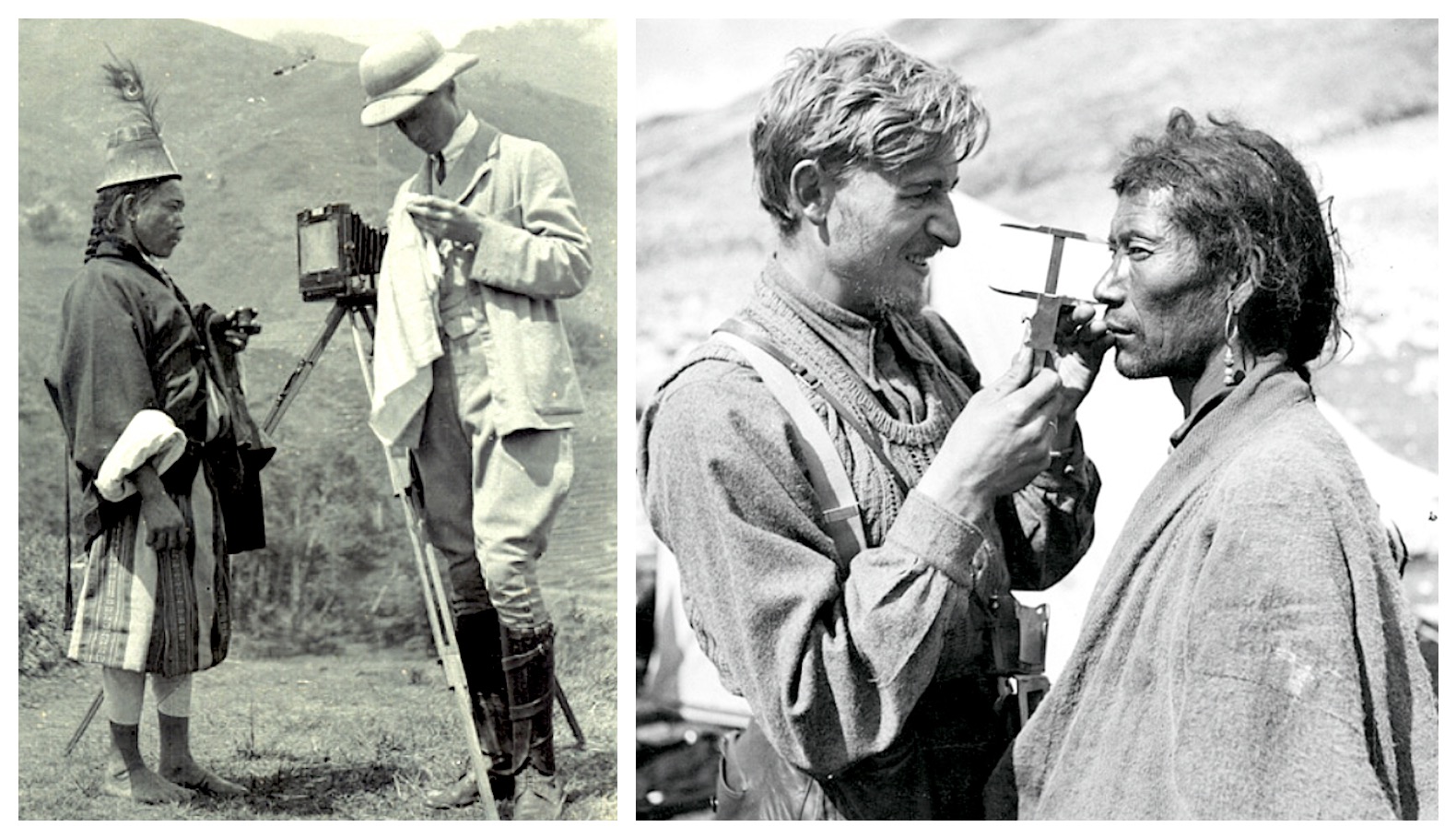

The whole business of “Tibet Photography” might have started out as a commercial swindle (of a mild kind) according to Dr. Claire Harris of Oxford. Tibet’s inaccessibility to foreigners did not deter certain Victorian photographers from creating exotic “fabrications of the fabled land” in neighboring Darjeeling and even making picture-postcards of such images available to English visitors to that famous hill station” –– along with, of course, such “native curios” as prayer-wheels, skull-bowls and ghost daggers (phurba) that even Kipling mentions being sold at Simla, way back when.

Such exotic photographs and postcards of “Thibetan Woman” on sale at the studios of Johnston & Hoffman and Thomas Paar in Darjeeling were innocent enough but some images definitely drifted into the area of fabrication, as when a senior lama and founder of the Yiga Choling monastery at Ghoom was dressed up as a roving mendicant (holding a souvenir prayer-wheel) and labeled “Lama”.

Then we get to unapologetically outright posed photographs claiming to be scenes of life in Tibet: a marriage ceremony, a religious service, picnickers dancing, a bandit waylaying a merchant and even a funeral scene – minus vultures but complete with an obligingly supine corpse, a sword wielding “dismemberer” and monks with drums, cymbals, bells, etc., performing funerary rites.

Nearly all these posed photographs were taken by the great Indian scholar/spy Sarat Chandra Das to illustrate his book Journey to Lhasa and Central Tibet (1904). As Das was in Tibet covertly he could not, of course, have gone around snapping pictures of actual Tibetan life. But our enterprising “pundit” did what was required of him (by his publishers) when he got back to Darjeeling with his bhootia friends. These images also possibly ended up in the lucrative picture-postcard market of Indian hill stations.

The book’s sub-section on photographic skullduggery in Darjeeling is merely the tip of the iceberg for Dr. Harris’s substantial and fascinating study. I think I could say that thus far PHOTOGRAPHY AND TIBET is possibly the most detailed investigative study on this subject. For instance she provides us numerous accounts and documentation not only of the travels but also photographs taken and equipment used by the long caravan of British colonial officials, Army officers, French and Swedish explorers, “pundit” spies, American missionaries, German ethnographers, Italian anthropologists, self-styled New York mystics, and all the other visitors to Tibet from the mid 1800s to the present day. Clare Harris does not seem to have missed out a single photographer of note who ever crossed the Nathu La.

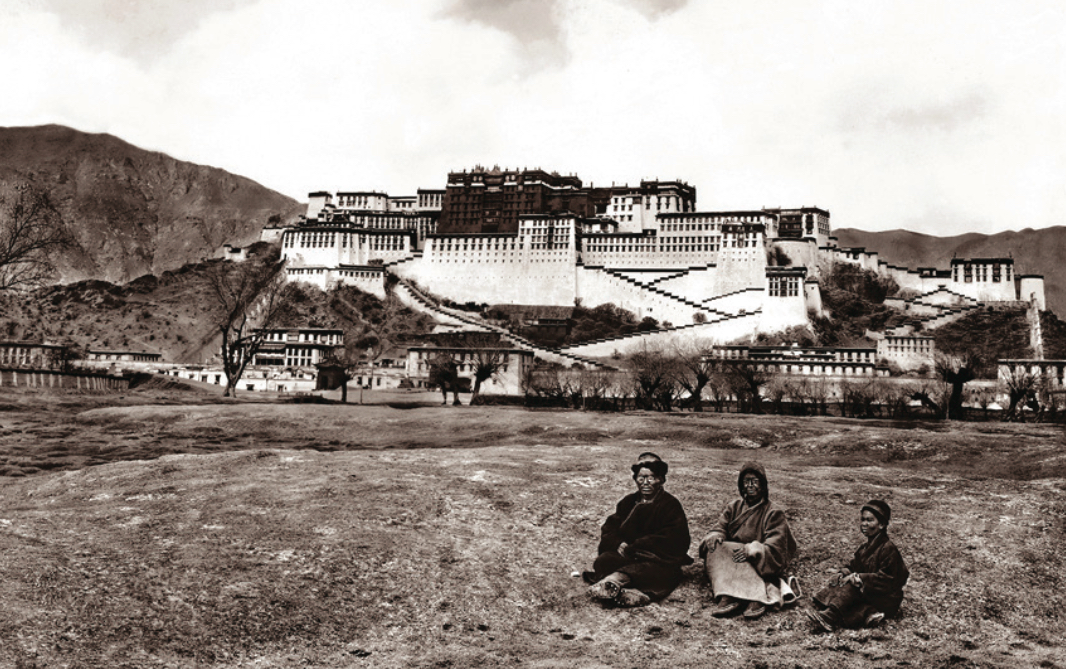

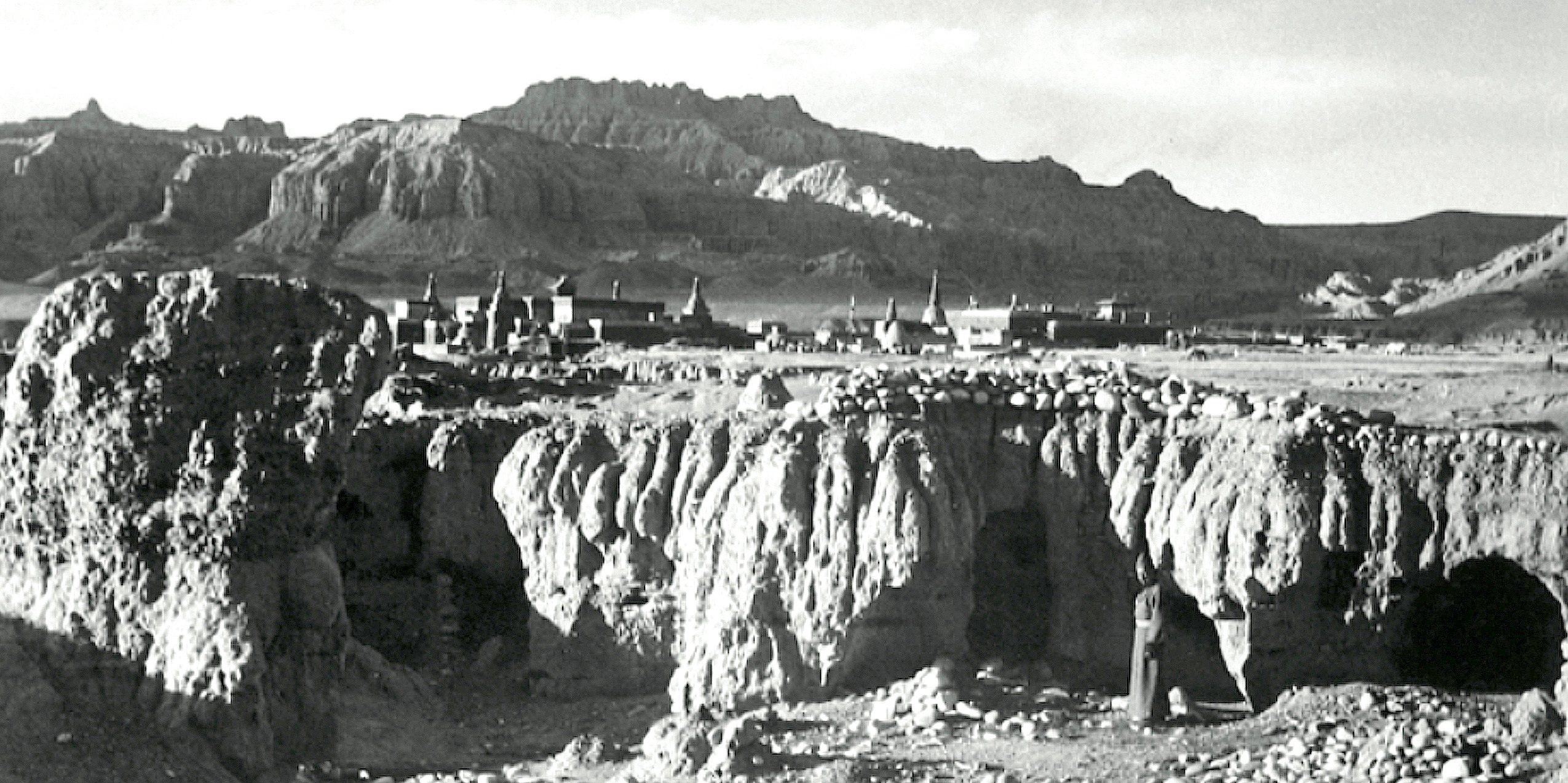

She does not of course overlook such intrepid women travelers and photographers as the renowned Alexandra David-Neel, but Dr. Harris also discusses the work of the Parsi artist and photographer, Li Gotami (wife of Anagarika Govinda) who from 1947 to 1949, recorded a whole series of black & white images of Tibet from the chapels of the amazing Kumbum Temple in Gyangtse all the way to the canyons of Tsaprang and the ancient monastic complex of Tholing in Western Tibet. Li Gotami’s photographs were published in Tibet in Pictures (1979). I own a copy of this slim book which I regard as an infinitely precious repository of visual memories of a bygone age.

Clare Harris also pins down the earliest indications of Tibetan enthusiasm for the camera. She claims it can be dated as far back as 1879 when the abbot of Tashilhunpo, Sengchen Tulku in a conversation with Sarat Chandra Das “confessed to a love of photography and revealed that he owned a box of lantern slides”. When Das admitted that he was an experienced photographer himself, the abbot asked Das for photography materials to be sent to Tashilhunpo. The two men also attempted to translate Gaston Tissandier’s A History and Handbook of Photography (1876) into Tibetan. Unfortunately “ .. no photographs made in Tibet either by the Sengchen Lama or by Das himself have yet come to light.”

Clare Harris somehow obtained rare copies of tentative photographs taken by the Panchen Lama in 1905, and even a glass plate reproduction of the image below – ‘photographed, processed and developed by the (13th) Dalai Lama himself,’ in 1912.

She provides us a near-complete inventory of pre ’59 Tibetan shutter-bugs: S.W. Ladenla, Tsarong (père et fils), Jigme Taring and others, and provides samples of their work. She also mentions the lama photographer Demo Trulku “… one of the early Tibetan aficionados of the camera” who was struggled during the Cultural Revolution for his reactionary crimes, possibly including his “decadent” hobby. Harris credits Photographer’s International XXXIX (1998) for the picture but it was more likely taken by Tsering Dorje (father of the poet and blogger Tsering Woeser) or perhaps the PLA photographer Lan Zhigui that Woeser-la mentions in part two of her essay on “Photography and the Cultural Revolution”

Clare Harris interviewed the 14th Dalai Lama in Dharamshala and asked him about his early interest in photography and whether he had been “fascinated by all types of cameras and could assemble and operate a cine-camera with some skill” as Heinrich Harrer has mentioned. His Holiness “… confirmed that he had learned a great deal from Harrer in Tibet and had continued to enjoy taking photographs in the early years of his exile in India. He also disclosed that he still treasured the Rolliflex he head acquired in the 1960s, though he regretted that in recent decades there had been little time to pursue his hobby. So, it is clear that Tenzin Gyatso was a keen photographer from childhood.”

Unfortunately, Dr. Harris did not obtain any sample of His Holiness’s work, which is a pity. The reader will have to be content with this charming photograph of the young Dalai Lama taken by the Tibetan/Sikkimese photographer Tseten Tashi (who had a photo-studio in Gangtok) in 1959. His Holiness is having a nice stroll down a street, probably in Dromo (Yatung) while bystanders keep a respectful distance in the background.

The book does not overlook present-day Tibetan photographers both in exile and also in occupied Tibet. We are provided analysis and examples of the works of the fashion photographer Tenzing Dakpa (Bylakuppe), the skilled but self-taught itinerant photographer Jigme Namdol (McLeod Ganj), the “talented young innovator” Nyema Droma (London) and the painter turned photographer Tsewang Tashi (Lhasa) . Dr. Harris also informs us that the 17th Karmapa is an accomplished photographer but provides us a meditative sky study by Tai Situ Rimpoche.

Clare Harris’s concludes her study on a suitably contemporary, even trendy, note with the internet story of a set of ‘Tibet Couple’s Wedding Photos’ that went viral on social media worldwide. “These images had been created by a Tibetan couple from the city of Chengdu who had chosen to portray themselves in a variety of sartorial modes and at different locations as they prepared for their nuptials. Within days of the release of these skilfully orchestrated pictures, 80 per cent of users of Weibo (the main social networking website in China) had seen them, constituting millions of viewers. That number expanded exponentially and into global dimensions when international news outlets such as CNN, the BBC, the New Yorker, the Indian Express and other Asian journals covered the story.”

Photography and Tibet is a richly informative and a hugely entertaining read. Professor Harris does, ocassionally, lapse into academese “… bodily praxis of proxemics and empowerment” etc., but these are forgivably few and far between. The bottom line –– for anyone with a passion for photography or Tibet, ideally both, this is an absolute must-have book.