Cultural Monuments of Tibet Michael Henss, Prestel; Box edition (November 12, 2014) A Review

From the 17th century to the beginning of the 20th, young educated Englishmen of means went on what was called the “Grand Tour” of continental Europe to expose themselves to the cultural legacy of Italy, France, Austria and even ancient Greece, and view the great works of art and architecture of the renaissance, and also of classical antiquity.

In old Tibet, many of the inhabitants of Kham and Amdo would also make a once-in-a-lifetime tour of the great religious and cultural centers of Lhasa, Ü (Central Tibet) and Tsang (South-Central Tibet). Resource and energy permitting, the pilgrims might travel further to Tö (Western Tibet), Mount Kailash and even further to Ngari (Far Western Tibet), Tsaprang the capital of the Guge kingdom and Thöling the seat of the second coming of Buddhism to Tibet.

It is important to bear in mind the nature of the ties that bound Khampas and Amdowas to Lhasa and Bhöd . This bond was not just to the Dalai Lama and the Gelukpa church, as some foreign writers have asserted. Even if a Khampa or Amdowa belonged to one of the other schools of Tibetan Buddhism: Kagyud, Nyingma, Sakya or even the pre-Buddhist Bön, his spiritual and cultural vision was still directed towards Bhöd, since the important institutions and centers, indeed even the origins of these belief systems, were located in Central Tibet.

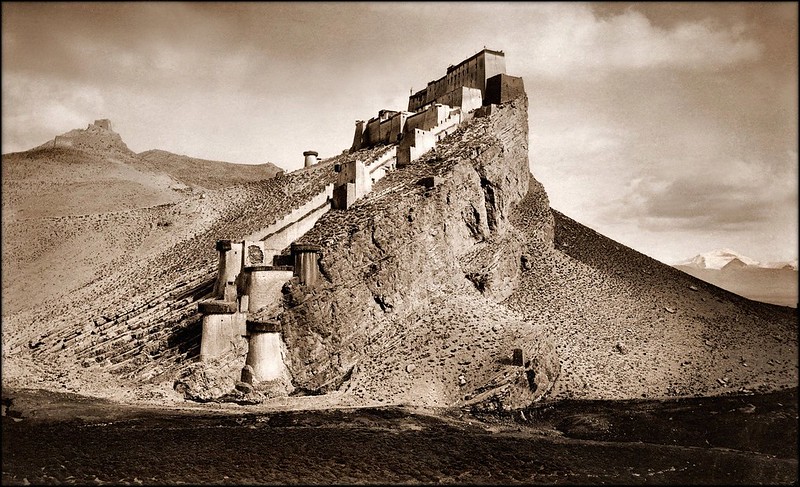

Of course the tour primarily served a religious purpose but it definitely had artistic, cultural and even historical meaning for the pilgrim. I once interviewed a Khampa from Nyarong, Aten Dogyaltsang, who told me of a pilgrimage he had made in 1939 where beside the great spiritual centers of Samye, Mindroling, Tashi Lhunpo, Gyangtse Kumbum, Sakya, Tsurphu, Drigung, Densathil, Sangri-Khamar and so on, he also visited the great fortresses of Shigatse Dzong, Gyangtse Dzong, Yambulhakar Castle and the tombs of the emperors at Chonggye.

Though Aten was a reasonably prosperous farmer he and his travel companions made the decision to beg for their food as far as was possible, in emulation of the Buddha’s great renunciation. The trip took Aten fourteen long months, and it was not only spiritually fulfilling but also an enormously enjoyable and an ultimately memorable experience.

There is, of course, no way those of us in-exile are going to make any such cultural journey in the near future. Even for our compatriots inside Tibet undertaking a trip from Kham or Amdo to Lhasa requires all sorts of hard-to-obtain official permits. And even after that, en route, our travellers are routinely stopped at multiple checkpoints and subjected to the most advanced electronic scrutiny and surveillance there is in the world.

But impossible as it may be for any one of us in exile to make such a journey as our ancestors did in the past, there is perhaps another way one could at least share, inspirationally as it were, in that great spiritual and cultural experience.

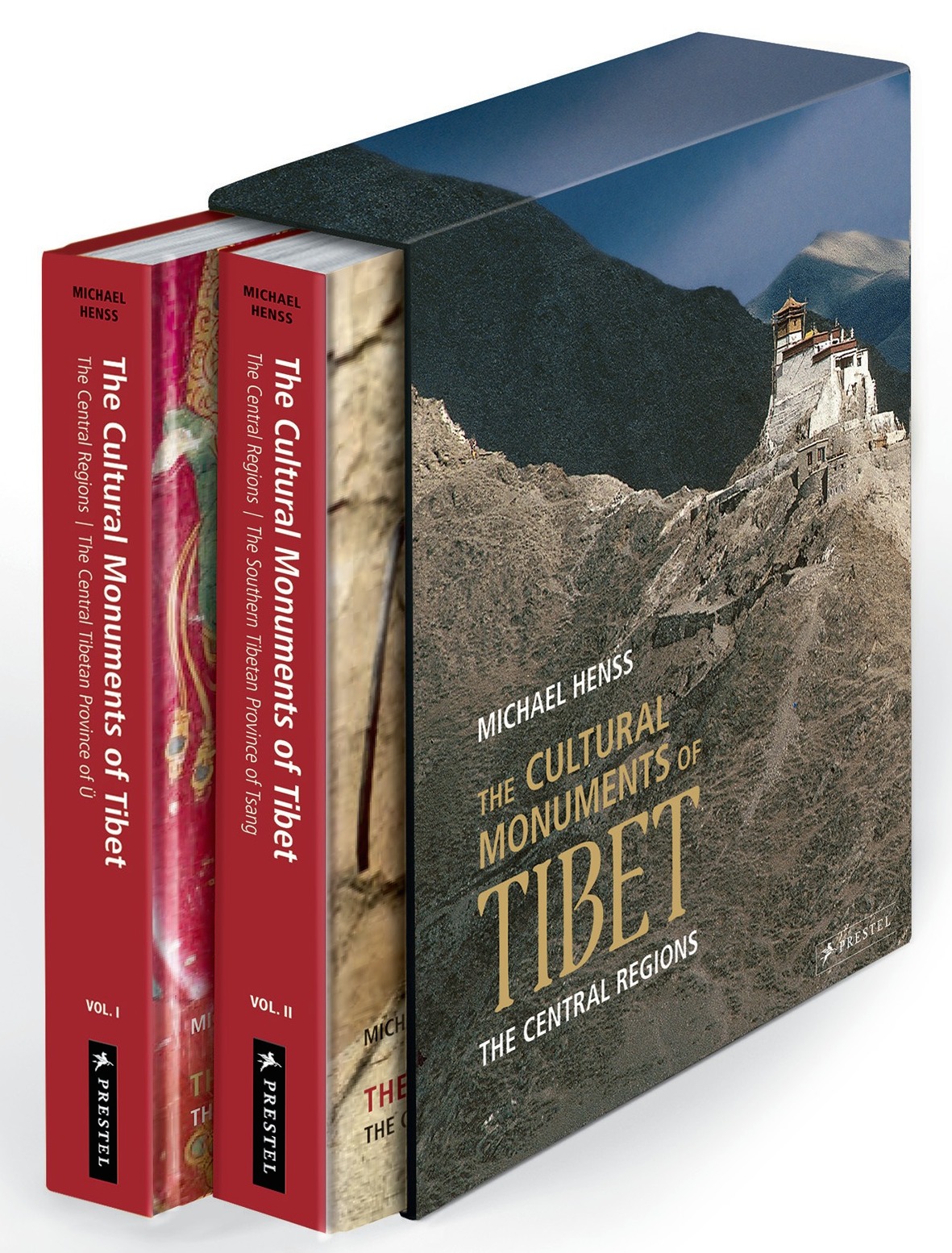

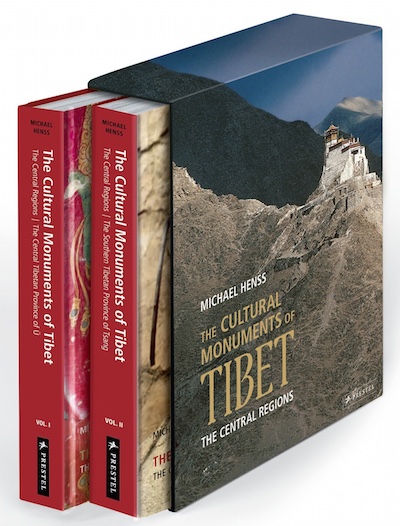

Some years ago I came across two beautifully produced volumes, The Cultural Monuments of Tibet, by the Swiss art historian Michael Henss. Focusing on Lhasa, Ü and Tsang, (plus a chapter on the Jhangtang and Zhangzhung) these two profusely illustrated volumes are the product not only of years of scholarship but also, importantly, of the many visits and field research trips the author made over the last thirty years. Providing a fundamental work of reference, they include over 1,100 illustrations most of them recent photographs by the author, and many rare and previously unpublished historical photographs, as well as over 100 architectural plans and drawings. Detailed descriptions and interpretations of the buildings, art, and furnishings of all major monasteries and significant secular buildings, as well as numerous references to both historical texts and to more contemporary works of scholarly research, make this work a unique source of information for both the specialist and the general reader.

What I found unusual and particularly enjoyable in Henss’ work were his inclusion of such peripheral artifacts and edifices generally overlooked in other similar works. For instance we get the fabulous golden throne masterminded by Andrug Gonpo Tashi and presented to the Dalai Lama by the people of Cholkha Sum in 1958, and also the old bell of the Catholic Church in Lhasa (1725-1745) built by the Capuchin mission and authorized by the seventh Dalai Lama Kalsang Gyatso.

For lovers of the macabre there is the scary oo-kyel or breath-delivery leather sack at Samye in which the Tseumara deity collected the life-force (tib. namshé) of people after they died. There is even a photograph of Songtsen Gampo’s wine jar (chogyal trungben) at the Jokhang.

Besides the countless monasteries and temples documented by Henss, he does not neglect the many ancient fortresses and castles of Tibet including such unusual examples as Gampa dzong, Go-shi dzong and even the ruins of Phari Dzong, destroyed by the British in 1903. Speaking of destruction, Hennes is careful to point the temples and monument destroyed and desecrated by the Chinese, and subsequently rebuilt. Wherever possible he provides old photographs of the original structures.

Weighing more than five kilograms Henss’ masterpiece is certainly too hefty a tome to lug around on a trip. Yet this is no mere guidebook but a vehicle in itself to transport the exile-bound Tibetan on a virtual pilgrimage of his cultural heritage. One reviewer writes “Imagine a book that takes you from valley to valley, place to place and monument to monument in the regions of Central Tibet,” and I absolutely agree. These two volumes were a magical experience for me. We Tibetans owe khewang Michael Henss a tremendous debt of gratitude for his astonishing lifework.

This Losar instead of giving a present of money to your children or relatives I think these two beautifully illustrated volumes would make an ultimate cultural gift –– and they are only US$ 213 on Amazon. Perhaps you could buy the books for your parents or your gyenla and then sit down with them and ask about the places in the book they might have visited in the past. In fact I think every Tibetan should own a copy of the Cultural Monuments and dip into it whenever possible, instead of turning on the news (what’s there to watch anyway?) or scrolling through Facebook or Instagram.

Remembering Tibet, in every precious detail, in every way we can possibly, should be the first fundamental undertaking of our common struggle. If we can just do that, then Tibet will always be ours. It will never be part of China.

Wow, an incredibly meaningful gift idea. I definitely want to get that now and gift it to my root Lama.

Glad you found it useful. Who is your root Lama? If I am not being nosey.

Sorry to respond so late, I wasn’t notified of a reply and I came back to this webpage to check the price of the two volumes. His title is His Holiness the Ninth Ogyen Tulku Rinpoche. I appreciate your engagement with your audience.

This is great. Thank you for continuing to write.

By the way, I recently read “Dawn of Tibet” by John Vincent Belleza. The book describes in length the archaeological survey on Zhang Zhung the author conducted in Western Tibet.

I found the book very interesting. According to it, our history is much older and richer than just the 1400 years of written Buddhist history.

TCL

Dear Tsering Choedon-la, Losar Tashi Delek. Nice hearing from you. Yes, Belezza’s Dawn of Tibet really pushes Tibetan history back a millenia or more. He wrote an earlier book on this subject published by the Library at Dharamshala. I don’t recall the exact title. Stay in touch. JN