TIBET’S FIRST WESTERN DOCTOR AND NOVELIST

(This obituary was written by Dr Pemba’s niece Dechen la. A slightly shorter version appeared in The Times (London) on Thursday 12 January 2012. All Tibetans in the Kalimpong/Darjeeling area remember Dr. Pemba la with great respect and affection for his humanitarian service to our exile community and for his kindness and unfailing sense of fun. For a traumatized and disoriented refugee community, just having a role model like Dr. Pemba la, who scored first in the Royal College of Surgeons exams in London, was a comforting reassurance that we would be able to cope with and even succeed in an alien and modern world. JN)

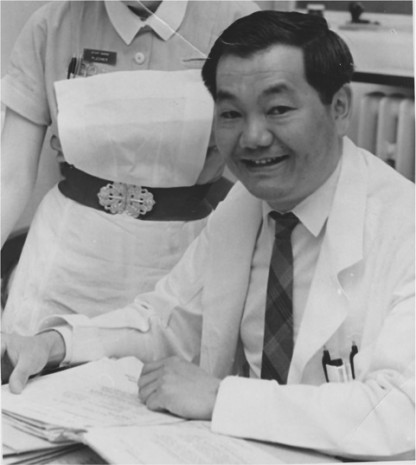

Dr. Tsewang Yishey Pemba was the first Tibetan to receive British medical qualifications and the first Tibetan to obtain a fellowship of the Royal College of Surgeons. He was founder of the first hospital in the Himalayan kingdom of Bhutan where he served as consultant physician to the Bhutanese Royal Family.

He was born in 1932 in Gyantse, the son of Pemba Tsering, a clerk at the British Trade Agency, who shortly after his son’s birth was promoted to Yatung township in the Chumbi Valley, wedged between Sikkim and Bhutan. Here, the young Pemba wandered the forests, scrambled about the Alpine-like valley and was brought up in the all-pervading religious daily life of Tibet. He was to recall, however: “We were not sweet cherubic Tibetan creatures, we would play ‘war’, and ‘captives’ would be whipped, sometimes so unpalatably that they would bawl enough to frighten a yak.”

When his father was posted to Tibet’s capital, Lhasa, he was cared for by his mother and grandmother, the latter having a great influence on him. “Granny came from Kham in the east and was famed her illicit, potent arrack which she distilled like some benign witch from Macbeth.” After a year, he, his mother and infant sister travelled to Lhasa, riding on ponies on a journey which he later likened to “something from the times of Chaucer and The Canterbury Tales.”

En-route, they crossed the 16,600-foot Kharu-La pass and crossed the Tsangpo River in coracles. In Lhasa they resided at the British legation in the Dekyi-Linka – ‘The Park of Happiness’.

On the 6th of October 1939, he witnessed the arrival of the new Dalai Lama, then a child, into Lhasa and sometimes, from his schoolyard, he would watch His Holiness carried by in his palanquin, within colourful, long, spectacular parades. On one occasion, he was blessed by His Holiness in his summer palace, the Norbhu-Linka – ‘The Jewel Park.’

One day in 1939, he was surprised to see a group of strange looking horsemen ride into the British legation at the Dekyi Linka where his family resided, “who had blond hair, blue eyes and dirty unkempt beards”. They were the scientists of the ‘Ernst Schaefer Tibet Expedition’ from Germany. A very sacred ceremony took place and all Europeans were requested not to photograph a certain image of a deity. “The Germans had not listened and were surrounded by a crowd who smashed their cameras. They were lucky to get away.” In October that year he witnessed the great excitement of the arrival of the new child Dalai Lama into Lhasa and later was once blessed by His Holiness.

In Lhasa he trod the holy circular “Lingkor Walk” where he saw certain highly polished rocks reputed to cure joint pains and years later, as a qualified doctor, he wrote, “certainly a place for harassed orthopaedic surgeons to send patients.”

He was the first Tibetan to obtain British medical qualifications

Tibetan schools just taught basics and wealthier Tibetans realised the need for better education for the country to modernise, so Pemba was sent to school in India, aged 9. He left behind the medieval Tibet of old: “Within a few years the Chinese Communists would change everything.” He was enrolled in Victoria School, near Darjeeling, where he excelled under Oxbridge teachers.

Not fluent in English, with no idea about cutlery, eating salad for the first time – which he compared to yak dung – and under strict routine, he was at first miserable. “I felt like a heavyweight boxer suddenly thrown on to the stage to perform Swan Lake.” He returned to Yatung in the first year’s holidays and fell seriously ill, being expected not to survive what was probably meningitis.

In 1949 he decided to study medicine in London. Living there, he discovered, needed much less mother wit than life in a Tibetan village; it was less strained than fighting high-altitude nature just to survive. He noted the trickiest thing to master was riding escalators.

He, like many Tibetans had wanted modernisation which arrived when the Chinese annexed Tibet in 1950. At first, they had little adverse effect on traditions but Karl Marx, he saw, had made his influence felt even in his remote boyhood home; something he wryly noted as a student when passing the British Museum, in which Marx had spent so much time.

Return to Tibet after his graduation in 1955 was impossible because of the Chinese occupation and the deaths of his parents in 1954 in a catastrophic flood disaster in Gyantse, the town of his birth. Instead, Jigme Dorji, later the Prime Minister of Bhutan, appointed him as medical officer to the kingdom. He moved to Paro, a town with little connection to the world outside its valley, where he took charge of turning an almost empty building erected in traditional Bhutanese style with a staff of two schoolboys into a hospital. Pemba wrote: “Bhutan was medieval, standing precariously on the edge of the abyss of modernity. Yet surprisingly, years later, when studying surgery, what helped most were the things I learnt in three years there.”

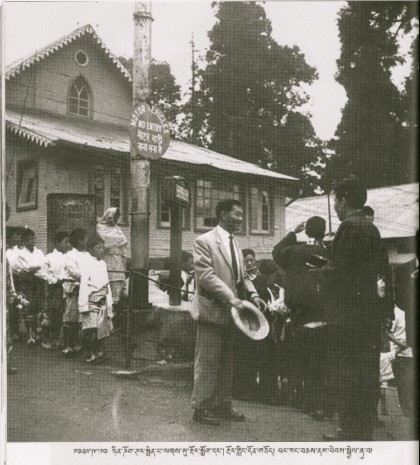

In 1959 he was appointed to the Dooars and Darjeeling Medical Association Hospital. The increasingly volatile situation in Tibet, culminating in March that year with the revolt against Chinese occupation, caused the Dalai Lama to flee into exile in India. After a massacre, thousands of refugees also escaped, many to Darjeeling. With the influx of so many into the small town, conditions became difficult and Pemba volunteered to help the sick. He counted many prominent Tibetan refugees as his patients and became well known in the region.

Pemba volunteered to work at the Tibetan Refugee School and Tibetan Refugee Self-Help Centre. For his medical work he became a well-known figure throughout the Himalayas and amongst many high-ranking Tibetan lamas he treated the 16th Karmapa, Dzongsar Khyentse Chökyi Lodrö, Dilgo Khyentse Rimpoche and Dudjom Rimpoche.

In 1965 he undertook further medical training in London to be a surgeon, gaining the Hallett Prize in 1966 for coming first in the primary examinations of the Royal College of Surgeons and obtained a fellowship in 1967. Returning to India, Pemba worked in Darjeeling and moved back to Bhutan in the mid 1980s as superintendent of the National Referral Hospital, remaining until 1992. Here he was an appointed United Nations Certifying doctor; sat on the committee devising the Bhutanese National Formulary and, in 1989, was a member of Bhutan’s delegation to the World Health Organisation in Geneva. During this time, Pemba served as consulting physician to the Bhutanese Royal Family. Retiring in 1992, he continued in private practice and from 2000 to 2005, made several visits to New York as a lecturer.

In 2007, Pemba finally returned to Tibet, describing his trip as, “a dream-like ethereal visit to my Tibet, capturing old memories, renewing ties and seeing a totally changed country.”

In his book Young Days in Tibet (1957), he observed the sometimes brutal justice system with its cruel punishments and debunked a lot of Western misconceptions. “The old remote, unchanging, isolated Tibet, supposedly strange and mysterious, asleep amidst the bustle of the 20th century was a false impression lavishly gilded by a legion of writers who created a paradise for armchair adventurers.” He recalled the filth of Lhasa’s streets and the frankness of the people, “speaking about bodily functions in a Rabelaisian manner – tellers of smutty jokes being held in as much awe as a Western master of after-dinner speeches.” Yet looked at coldly, he could not avoid admitting that Tibet “had the ingredients of romance and mystery in her unique system of incarnate lamas, feudal pomp and pageantry, monasteries and hermits, altitude and dirt, tough happy-go-lucky people and countryside untouched by the forces of modern life.” In 1966 he wrote Idols on the Path, an autobiographical novel, regarded as the first fictional book in English by a Tibetan, in which he painted a picture of Tibet before and after Chinese Communist occupation.

He correctly prophesied that should the Chinese ever attack Tibetan Buddhist faith they would encounter resistance and hatred. He followed this in 1966 with “Idols on the Path”, an a novel of vivid contrasts which encompasses a century of barbarous injustice that Tibet has suffered (twice invaded – in 1904 by the British and in 1950 by the Chinese), with a passionate, evocative, autobiographical slant.

Beyond the medical profession, Pemba followed the arts and writing; his final manuscript remains unpublished. In a written contribution to his peers for a reunion in 2010 at University College Hospital, London, which he could not attend, he wrote of his latter daily routine, “I try to be Aware: to Contemplate: to Understand. Minding this Supreme Triad enjoined by our venerable Tibetan sages. All other activities of this life, they preach, are mere ‘chasing of shadows’. Meanwhile I sit quietly, watching the sun set over the Himalayan peaks. T.S. Eliot’s words disturb me:

‘With the voices singing in our ears saying That this was all folly’.”

He is survived by his wife, Tsering Sangmo, four children. A fifth child predeceased him in 2009.

Tsewang Yishey Pemba, surgeon, was born on June 5, 1932. He died on November 26, 2011.

I had the good fortune of meeting with Dr.Pemba la a few years ago.

A special person and the term ‘larger than life’ would be the best way to describe him,he will be missed

And how is Dechen Pemba related to Tibetan historian Tsering Sakya?

Another sequoia falls.

Thank you Jamyang Norbu la for sharing this. Dr. Pemba’s brother is married to Tsering Shakya’s sister.

Condolence from all the readers of this blog! (Presuming that all the readers share the same feeling). There seemed to have a time when Tibetan patients from all parts of India longed to visit Darjeeling, in hopes to get his treatment.Since he was the first Tibetan allopathic doctor, there will be a chain of doctors like him Tibetan society, for that is how Tibetan “tendrel” is believed to work.

Looking back at about a year’s series of interesting postings on this blog, from defending “tsampa” to obituary of Doctor Pemba, it is almost a year on since this comment maker has come across this blog, and not only has maintained a frequent visit but also participated in making tiny comments here and there.

This is a unique blog of its kind, where readers’ comments have instant access with no modification or restriction of any kind—a real freedom of speech!

The blog author must be thanked for sharing his brilliant thoughts with such openness. One can’t help but wish that a person with such quality be present in the exiled parliament. If he wish so, he will have a landslide win. That is for sure.

Chinese Engineer and New Generation also deserve acknowledgement for their outspoken criticisms, especially NG’s harsh “kudra” reprimands!

Hoping that the new year will have many surprises for us all!

I never met Dr Pemba or had a word with him. I spent most of my life in Darjeeling and he was then a physician at Darjeeling’s “better” hospital commonly known as Planters hospital because of its association with tea growers in the region. My memories of him are images of him seeing from distance only a couple of times but one of them has imprinted itself onto my mind as clearly as it was then and it flash before my eyes whenever I hear his name. Maybe it’s due to the gravity of impression this single act has created in me, that’s despite being successful and famous he hadnt forgotten his roots.

Dr Pemba was a slightly round man and his both cheeks stretched almost perpetually in semi smile. It was sometime in early 90s, I was in college then, Tibetan community of Darjeeling had organized a program at Bhanu Bhavan, an auditorium located behind Chowrasta which is now renamed as Gorkha Rangmanch Bhavan. His Holiness’s throne was set up on the stage and a picture of him sitting atop. I was in the audience. I dont recall what it was for but community leaders and invited guests went on stage to pay respect to His Holiness, they offered khatak and bowed beneath the portrait. When Dr Pemba’s turn came, unlike the others, he prostrated three times before HH’s portrait before offering the scarf and bowing with folded hands as if breaking the pattern of obeisance people were observing there and adding something new from his side to it. He then gave speech with anecdotes from his early life in Tibet….

Om mani pedme hung…

sad for losing such great soul ,,,,

My 23 years in exile never heard Dr. Pemba. However it is sad to heard he was passed aways.

May he reborn as a Tibetan and serve our community again.

I was born and brought up in Darjeeling. And I remember very well that he practiced at planters hospital(rich people`s hospital),where so very few exiles can afford to go at that time. So above mentioned humanitarian service to our exile community seems untrue.

om mani pame hung

may his soul in peace.

I remember Dr Pemba la. He was a very kind man and for many years offered his services free to us in the CST Darjeeling school. I also know for fact that he was very kind to indigent Tibetans who came to his hospital; they were never charged a dime and on many occasions provided free medicines also. Even when he was working in Bhutan, Tibetans there benefited from his services. He was a patriotic Tibetan and a great role model. I am saddened by his demise. I never had a chance to thank him for the medical care he has given us and want to say Thank you Dr. Pemba la here. I offer my condolences to his family. There was a long article in Tibetan News Paper printed in Darleeling praising Dr Pemba la for his humanitarian service but I forgot the date and name of the paper now. Perhaps, the paper was called “Rawang Ranzen” or “Sheja”. I know it is no longer printed now.

He used to visit for an hour to cst darjeeling every saturday for some years. Yes, he was very kind man and real gentleman.

There was other kind tibetan doctor as well who give free medicine and dont take any penny from some poor tibetans and locals. In Kalimpong I heard Dr. Sonam Dakpala used to do that. These days Dr. Lobsangla of Sarder hospital is doing the same. I heard he even sometime give money from his own pocket to buy medicine.

There are like these people. But to say humanitarian service to exile community to me is little too much.

Thank you Jamyang Norbu La for making us aware of this great personality..may he born in a buddhist family…….

i am one of those unfortunate guys who have not heard about dr.pemba least of all meet him in real life.. after reading jamyangla’s blog , i am convinced that he truly is a man of inspiration and action. his life is the testimony to his greatness. may your soul live in peace..