At the request of the organizers of the TIBETAN INDEPENDENCE DAY celebration at New York City, on the 13 of February 2013, I was asked to give a talk on the background story, as it were, of the events and personalities that contributed to the creation of an independent Tibet in 1913. JN.

The profound historical events that led to the 13th Dalai Lama’s decree of Tibetan independence on February 13th 1913, came about because of the intersection of Tibetan history with that of two major imperial powers in the world, the first, a powerful and aggressive British Empire, the other a weak decaying Manchu empire, attempting to maintain a shaky protectorate in Tibet.

A seemingly innocuous diplomatic agreement led to the unfolding of these events and the first military conflict between Tibet and Britain. In 1876 Britain and Imperial China signed the Chefoo convention, one article of which permitted the British to send an exploratory mission through Tibet. But since Tibet had not been consulted, the Tibetan parliament the Tsongdu refused to allow the British mission entry to Tibet. The Tibetan response also reflected its anger at Britain’s advances into Sikkim which Tibet regarded as within its own sphere of influence.

As a gesture of defiance to Britain and China, Tibetans erected fortifications at Lungthur thirteen miles into what the British regarded as Sikkim territory and garrisoned the fort with nine hundred soldiers. According to the English scholar L. A. Waddell the Tibetans actually invaded Sikkim “and advanced to within sixty miles of Darjeeling, causing a panic in that European sanitarium.” The British sent two thousand soldiers and artillery under Brigadier Graham to expel the Tibetans. Artillery bombardment and infantry charges finally drove Tibetans back from Lungthur. “But the Tibetans, despite their primitive equipment were not dismayed by this show of force.”

In May they attempted a surprise attack on the British camp at Nak-thang and “…nearly succeeded in capturing the Lieutenant-Governor of Bengal, who was visiting the frontier; but they were repulsed with severe losses.” Waddell mentions that the Tibetans fought fiercely and showed “great courage and determination.” In spite of the major setbacks the Tibetans stubbornly refused to acknowledge Britain’s right to send a mission to Tibet, nor China’s right to grant permission for such a venture.

Tibetan intransigence persuaded the British to give up their exploratory mission into Tibet. Instead Britain secured China’s recognition of its military takeover of Burma, and reciprocated by recognizing China’s claim of suzerainty over Tibet.

Tibetans were deliberately excluded from all the conventions and discussions that took place in those years between the British and China concerning Tibet or Sikkim. In 1893 when the Trade Regulation talks were held in Darjeeling, the Tibetan cabinet sent a senior official, Paljor Dorje Shatra to keep an eye on the proceedings. Shatra’s presence appears to have been resented by the British. Some English subalterns dragged him off his horse and threw him into a public fountain in the Chowrasta square.

It should be noted that Tibet’s rejection of Britain’s Tibet policy was maintained consistently for nearly three decades. Finally in 1904 the Viceroy of India Lord Curzon sent the Younghusband expedition to Tibet. The British invasion force with its repeating rifles, artillery and maxim heavy machine guns massacred seven hundred Tibetan country levees at the hot springs of Chumi Shengo, in the space of two hours. “Despite this withering attack, the Tibetan forces fell back in good order, refusing to turn their backs or run, and holding off cavalry pursuit at bayonet point” A few thousand more Tibetans died for their Homeland in subsequent battles at Samada, Gangmar, Neyning, Zamdang, and most significantly at Gyangtse, where the Tibetans besieged the British force for a time before the conflict ended and the British marched into Lhasa. But the Thirteenth Dalai Lama had already escaped to Mongolia, so the British forced a treaty, the Lhasa convention, on the Tibetan cabinet in August 1904, and then returned to India.

Tibetans can legitimately view the events from 1876 to 1904 as the first chapter in their modern history. Most accounts of this period, largely written by British officials or scholars tend to downplay native resistance and patriotism and ascribe them instead to Tibetan ignorance and religious fanaticism, fanned by sinister monks and xenophobic lamas.

The destruction of the small Tibetan army and the undermining of the Lhasa government created a dangerous power vacuum in Tibet, which was exacerbated by the hasty withdrawal of British forces. The next year, in 1905, the energetic and ruthless Imperial viceroy of Sichuan province, Zhao Erhfeng, invaded and captured large areas of Eastern Tibet, burned down many monasteries, butchered thousands of monks and quite literally extinguished the lines of a number of ancient independent and semi-independent Tibetan kings and rulers on the Sino-Tibetan frontier. The people of Kham were terrorized by the Chinese army. I came across an old National Geographic magazine which had an eyewitness account by the American missionary Dr Albert Shelton, of Chinese atrocities. Shelton writes of Chinese soldiers boiling Khampas alive in a giant brass cauldron normally used for making tea for the monk congregation of Drayak monastery. An actual photograph of the cauldron is provided.

The first large-scale population transfer of Chinese peasants, ex-soldiers and lumpen elements from cities as Chengdu and Yaan to Tibet was, with European and American missionary support, set in motion. Zhao in a memorial to the throne described his grand enterprise in Eastern Tibet “…as a colonial one, comparable to those of the British, French, Japanese and Americans in Asia and Africa.”

Finally on 12 February 1910, the Chinese invasion force approached Lhasa. The Thirteenth Dalai Lama had hardly returned to his own capital city a little more than a month earlier. His Holiness, accompanied by a few ministers, some officials and a small detachment of soldiers, once again fled the city. The Dalai Lama took with him his new seal of office, which the National Assembly had presented to him some day earlier on behalf of the Tibetan people. This time the Dalai Lama and his entourage headed southwest towards British India.

Since Tibet had signed the Lhasa convention and now allowed the British a number of trade and diplomatic privileges, the Dalai Lama hoped for some support from Britain. But he was badly disappointed. His overtures to Russia also proved fruitless. In India he and his exile court used their time to see new things: for instance factories, hospitals, British warships and other developments of modern British India. One might speculate that the 13th Dalai Lama and his officials were influenced by the spirit of modernization, social reform and nationalism that was spreading throughout Asia at the time, exemplified by the Meiji Ishin, the dramatic and revolutionary modernization of a formerly feudal and xenophobic Japan. Around the same period in India, a profound social and intellectual awakening took place within educated Indian society. Referred to as the Bengal Renaissance this movement can be seen as a precursor to India’s independence struggle. It would be reasonable to speculate that this social awakening in India did have some impact on the exile Tibetans; after all they were based in the township of Darjeeling, which was the summer capital of the Bengal government.

Behind the young and, might we say “nationalist” Dalai Lama there were a number of loyal, capable, even relatively progressive officials who formed the “Nationalist party” that Waddell describes as having saved His Holiness from the machinations of the Demo Regent and the Chinese Amban in Lhasa. The foremost member of this unique company was certainly the Lonchen Shatra, Paljor Dorje, intelligent, sophisticated, meticulous, “ever the trained diplomatist”, according to Sir Henry MacMahon.

Another important personality of this period, who might be considered a seminal figure in bringing about the reformist and nationalist awakening in the court of the young Dalai Lama, has by and large been overlooked.

The Buriat lama, Agvan Dorjiev’s role in modern Tibetan history has thus far not been sufficiently acknowledged, thanks in large part to British reports and accounts, which invariably relegate him to the role of a sinister Russian spy. He first came to Lhasa in 1873, to study at Drepung monastery where he obtained his geshe degree. Dorjiev, whose Tibetan name was Ngawang Lobsang, became one of the seven tsenshabs or debating partners of the young Dalai Lama. In 1888 he became a confidant and tutor to the Dalai Lama.

The young Dalai Lama’s tutor, according to his biographer John Snelling, “… was very much a man of the world. Dorjiev’s “modern, progressive turn of mind” gained from his extensive travels. He visited St. Petersburg, Paris, London, and major cities in India and China. The scholarly consensus now is that Dorjiev was no foreign spy but a patriot who worked tirelessly to free Tibet and Mongolia. Dorjiev was one of the main authors of the historic Tibet Mongolia Treaty signed on 29th of December 1912. The treaty is emphatic in declaring the complete independence of Tibet and Mongolia, their rejection of Manchu rule, and their absolute severance of political ties to China.

Two years into the Dalai Lama’s exile in Darjeeling revolution broke out in China, and Imperial troops in Tibet unleashed a reign of terror on the population. From Darjeeling the 13th Dalai Lama sent his trusted officials to Lhasa to take charge of the resistance. On the 26th of March 1912 Tibetans formally declared war. After nearly a year of hard and brutal fighting, the Chinese surrendered, and Tibet became an independent nation.

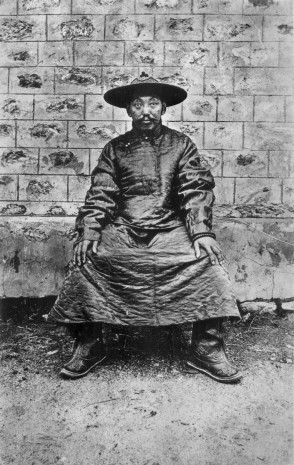

The Thirteenth Dalai Lama returned to Tibet on the 10th day of the 5th month of the Water Mouse Year (June 1912). There is a photograph of him taken at Bhutan House in Kalimpong just before his departure. He is wearing the broad-brimmed thangshu or thangsha hat for protection against the sun. There is another photograph of His Holiness wearing the same hat and riding a mule in July of 1912 when he arrived at Ralung in Tsang province and met the Panchen Lama. His Holiness entered Lhasa on the 16th day of the twelfth month of the Water Mouse Year (January 1913) where thousands lined the streets to greet him.

One month later he promulgated the decree reasserting the independence of Tibet. The same decree whose centenary we are celebrating today.

Phayul reports:

“Sikyong Sangay, who is currently on an official trip to the United States, further called on national governments and international agencies, including the United Nations, to “use their good offices and actively engage with China to stop the deteriorating situation in Tibet by addressing the genuine grievances of the Tibetans.” ( Self-Immolations – Ultimate Acts of Civil Disobedience: Sikyong Sangay, Thursday, Feburary 14th,2013)

Visiting his family to celebrate Losar , while Tibetans are on fire in Tibet and in Nepal, is not an official trip to United States.

This is an observation of many of Boston Tibetans.

What is front and center this Tibetan New Year, was that Gangchen Kyishong was devoid of the whole Kashag with Sikyong sending the Kalons to celebrate Losar with their families and relatives around the world. One hopes that are doing so at their own personal time and money as hinted in the above post! But I have my own doubts about it. For instance, the Office of Tibet in North America has ordered the Tibetan Associations Kalons are visiting many places around March 10th events and that they would be addressing local Tibetan communities. It is not known what they will talk about, but it sounds official.

One hopes the local Tibetans will them about it. Also, I suspect they will be asked about CTA’s murky role in the Radio Free Asia turmoil.

I am hearing more and more on Religious freedom/human rights….who the fk imported these words into our community.

Daveno: H.H the 14th Dalai Lama.

TD, When? Any evidence to back up? Any evidence that those words are not imposed upon by outside thirdparty player?

the whole exile charter is based on that. Dude, what have you been?

you are moving from HHDL to Charter of tibetan administration.

I wonder, what was the point of asking such retarded questions DAVENO?

It’s as obvious as the nose on your face, that, since the Dalai Lama’s middle way doctrine ceded the demands for Rangzen; religious freedom/human rights, etc, are used as substitute catchphrases in an attempt to capture the world’s attention to the plight and daily anguish of our hapless brothers and sisters in Tibet at the hands of cruel, sadistic China.

Regarding whether a third party imported these slogans or not, who freaking cares when dirty deeds were done dirt cheap decades ago.

Are we against religious freedom? human rights? Obviously not!

Anyway, what other shibboleth can the Middle Pather’s hurl at China from their crumbled bastions of castle Appeasement?

I wonder when “Chinese engineer” became the scientist- full of dirt?

There is no middle pather or rangzen pather so long as there is tsampa blood running inside..all against the dirt cheap chinese ‘the master amoung the thieves and eating any shit that moves…

The point is obvious to even a grade 3 kids..you moron.

Jamyang-la, I was at the morning session today and I’m sorry I wasn’t able to stick around. I had to get back to Boston, but it didn’t occur to me till afterward that one of the issues people have with history is that it isn’t “living” for them. You mentioned how it is often perceived as dry dust and yet, the uses of history in political discourse are telling.

A case in point was some years back when at the Kennedy School of Government, Lobsang Sengay did a fine job of parlaying with some Chinese colleagues of his from Harvard Law School (if memory serves); interestingly, Lobsang brought up several points of history and his Chinese colleagues were palpably uncomfortable. They contended that what was past was past. Yet to buttress their arguments, they had to refer to (admittedly, *their* version of) history.

In any event, a couple of things I wanted to share with you is that an awful lot of the younger Tibetans I’ve met who are recent refugees want a regime change in Tibet, and they don’t understand why there isn’t more buy-in from the West. A really good friend of mine in Dhasa has stated that he wants very much to be a part of the government in exile because he feels like he’s not well-represented as a recent exile. He was respectful of Lobsang, but reticent when it came to talking about what kind of leader he is turning out to be.

I talked to Lhasang Tsering a fair amount and I wonder if it isn’t time for some of the old lions like you and Lhasang-la to lead the discussion even more (god knows you’ve both been leading more than your fair share, but as a non-Tibetan, leadership even for discussion about independence is sadly lacking amongst the exile population’ though after talking to those younger and more recent refugees, they want that on the table.)

Last, I don’t have Lhasang’s latest info, but do you know if he’s finished his latest book? The missus was a little miffed that he left her with the shop and went off to do some writing. That was back last March before I came back to the states.

All the best,

John

The reason why there is almost nil buy-in from westerners or any foreigners is because the “middle way doctrine” has castrated the Tibetan diaspora. Now we lay down our fat oily behinds on Chinese made sofas and rouse ourselves occasionally to wag our fingers at anyone who tries to do something for Free Tibet.

The torch of Independence has passed from the 13th Dalai Lama into the hands of people like Jamyang Norbu, Lobsang Sangay, 14th Dalai Lama, and Tsering Woeser,etc, to keep the fire burning, to keep the hope alive.

Sometimes a fire flares into a mighty conflagration, at other times, it’s just a flicker on the end of a precarious wick. As long as there is a spark, there is hope for fire.

The metaphor of fire and torch, when so many Tibetans have set themselves alight, may seem cold or calculating, yet many a civilizations have, in the annals of world history, com-busted from the fuel of immaterial hope.

Anyhow.

Our very own Woeser la won the international women’s courage award, the Sikyong Dr. Lobsang Sangay, in a wonderful gesture, sends his kudos to Tsering Woeser, unfortunately, being under house arrest, Woeser la is unable to accept the honor in person. She dedicates her award to the, over hundred self-immolators who have “bathe their bodies in fire”.

Secretary of State John Kerry need to pay a state visit to Tsering Woeser just as the former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton (and Obama) did for Aung San Suu Kyi.

The only problem I have with Tsering Woeser is that she has Han blood coursing thru her veins, worse, she is a Woman, and her father a high ranking Army officer in the People’s Liberation Army. Are we bothered by that? Should we be bothered by that?

I don’t feel comfortable with a strong willed Tibetan Woman, majority Tibetans will agree, women belong in the kitchen, not in politics.

best of luck trying to catch a fly with that, Owl. Maybe the slobbering fool will jump on that, who knows. We shall see.

Jamnor-la,

May I take the liberty to post here the piece below if you think it is bit off the stuffs the blog is meant for?

A HEARTY TASHI DELEK TO YOU, WOESER-LA.

Again you made it.It is terrific!

You are a women of brave heart and a smart head. Not only that, but both being in the right place makes you a force that bothers the CCP.It must be furious with you by now.

A true daughter of Tibet in action, when your life is on the wire all the time because you are right in the mouth of the evil DRAGON.Its merciless jaws can close at any moment. But so far it hasn’t happened. It’s a miracle!

From the very depth of my heart,I entreat the Palden Lhamo to take the charge of that miracle so that it remains with you like your own shadow.

You need miracle very badly because to carry out your mission for Tibet,you will have to remain tantalisingly trapped in the dragon’s claws for months and years to came.

To the mortals, please keep on heaping awards on Tsering Woeser.It not only goes a long way to protect her, but she also deserve them because her stuffs have punch with dignity, defiance and above all the light of the TRUTH.

Yours admiringly,

Gyaltsen Wangchuk

P.S.

Normally I agree with what the Owl writes because,in my opinion,he not only writes well but his head is in the right place. But this time my answer to his two questions is NO. And I am a bit at loss with his last paragraph. Perhaps he is just joking.If meanly seriously, please don’t take offense with my remark.

By the way, if it is she owl,forgive me for missing the”S” everywhere. GW.

I saw this representative of the Tibetan government in NY on Youtube saying there is freedom of speech for Tibetans and yet implying with almost every other paragraph in his speech that Tibetans who are for Rangzen are against His Holiness. I expected more from that office. When people in their position indulge in creating rift in the community instead of healing it we have elected or selected the wrong people to head us. I am so glad that HH has specifically announced that when Tibet is free, Tibetans inside Tibet will lead us and not by these neta like Tibetan politicians. Equipped with lots of clever sounding words but disingenuous at heart.