This article first appeared in Lungta No 15, The Singing Mask, Echoes of Tibetan Opera. I must thank the guest editor, Isabelle Henrion-Dourcy, and editor (and leading Tibetan scholar) Tashi Tsering for their invaluable help and guidance.

The Wandering Goddess

Reviving and Sustaining the Spirit of Ache Lhamo in Exile

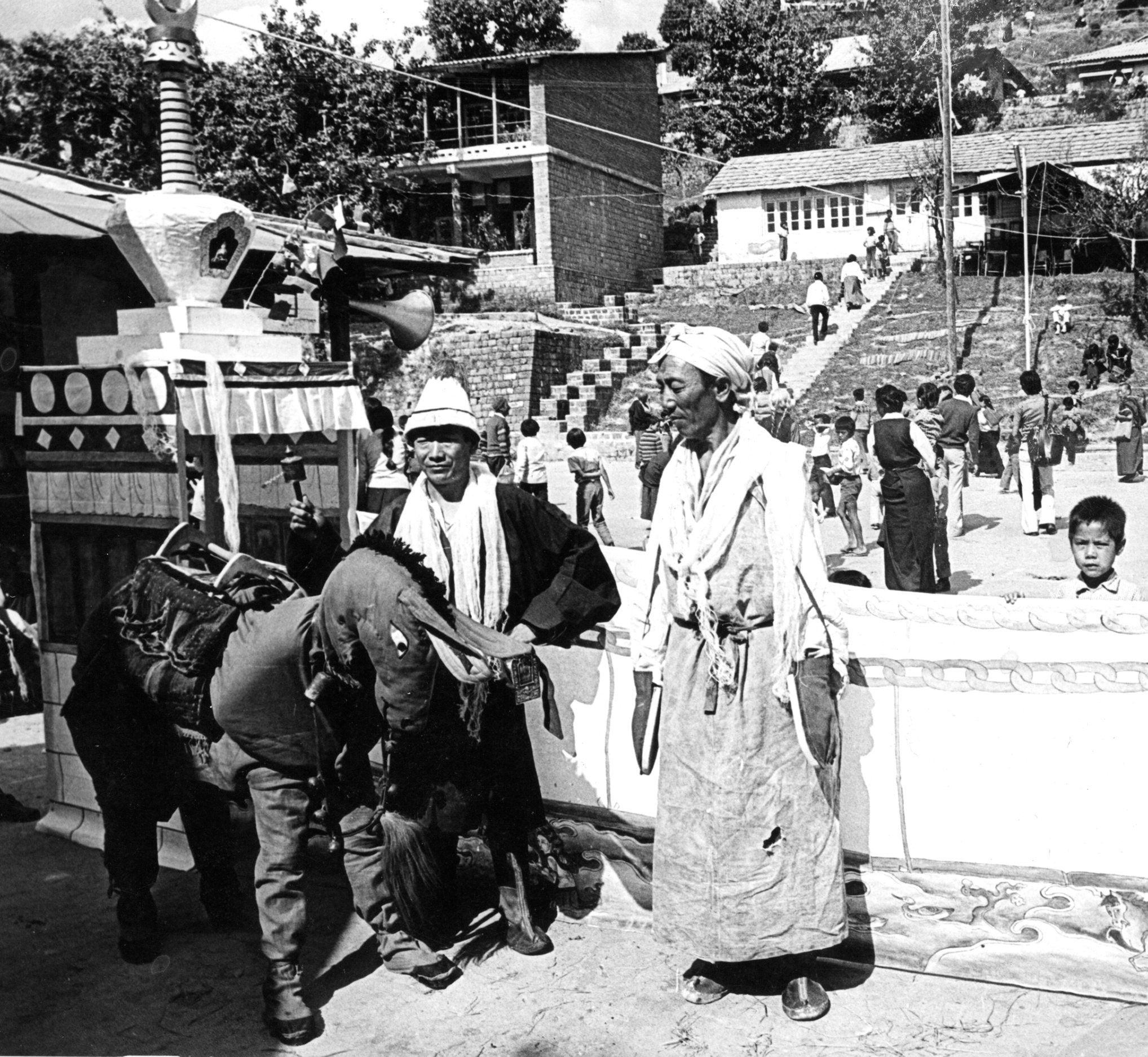

The revival, in exile, of Tibetan opera or Ache Lhamo took place in the late fifties and early sixties in Kalimpong, a north Indian frontier town bordering Sikkim and Bhutan. It was once home to a flourishing community of Tibetan traders, craftsmen and some émigré aristocrats and lamas. Kalimpong, in the old days, was one of the few ‘foreign’ destinations of touring opera performers mainly from the Kyurmulung (sKyor-mo-lung) company that hailed from Lhasa city. Since this was the only opera company whose members were not farmers, it was required of these performers that, after the annual opera festival at Drepung, Lhasa and Sera they tour the countryside to maintain their skills and earn a living. They sometimes even traveled beyond Tibet to Sikkim and Kalimpong. The government office in charge of the opera companies was the Treasury Office (‘Phral-bde las-khungs or rTse-phyag las-khungs) – which, incidentally, was also responsible for managing the Shoton (zho-ston) opera festival and all things concerning opera.

So even before the Tibetan Diaspora, there were already a few Kyurmulung opera performers in Kalimpong and more importantly, a community of opera aficionados in that town. Yet in the fifties more immediate matters than opera concerned most Tibetans in Kalimpong and elsewhere; what with the Chinese occupation of Tibet, the violent uprisings in Eastern Tibet, and the steady flow of expatriates, agents of the resistance, and refugees to that frontier town.

Perhaps it should be mentioned that at the time in Kalimpong, there was an exceptionally fine amateur opera singer who was also a bard (sgrung-mkhan), a singer of the Tibetan Gesar epic. He had been a court entertainer (and personal bard) to the former regent of Tibet, Reting Rimpoche. Some of the early Tibetologues who lived in Kalimpong then, as George Roerich and René de Nebesky-Wojkowitz probably heard their first namthar, or opera aria, from this artiste, Jampa Sangdag. He was also a language teacher and informant to Prince Peter of Greece and Denmark, an anthropologist and Tibetologist, and also informant to the French scholar R.A. Stein. The Tibetologists Alexander and ArianeMacdonald also appear to have met Jampa Sangdag in Kalimpong around the fifties.

In 1959 concerned Tibetan residents of Kalimpong set up a performing troupe to promote awareness of the Tibetan issue in the Indian public, and to raise funds for the growing flood of refugees. The members of this troupe came from a fairly diverse background: professional Lhasa musicians, opera performers and children of Khampa merchants and émigré aristocrats. Their program consisted of a variety of colorful folk dances with traditional musical accompaniment. To liven up their show excerpts from Tibetan opera like the ‘Dance of the Wild Yaks’ (Yak-tse g.yag-rtsed or Shel-grong ‘brong-rtsed) were included. This item is still a big favorite with Indian audiences.

After the establishment of the Tibetan government-in-exile at Mussoorie in 1959, and its relocation to Dharamshala in April 1960, this embryonic performing troupe in Kalimpong was summoned to Dharamshala to become the official performing arts institute of the Tibetan government-in-exile and was called the Tibetan Historical and Cultural Drama Party (bhod ki gyalrap rigshung zlos-gar tshogs-pa) which was later changed to the Tibetan Music, Dance and Drama Society, or Bhod ki Dhoegar Tsokpa (bhod ki zlos-gar tshogs-pa) in Tibetan. It became the present Tibetan Institute of Performing Arts in 1981 when I took over, but still claims its founding date to be the 11th of August 1959 (at Kalimpong) and boasts of being the first Institute of its kind to be established in exile.

In 1961, the professional opera performer Norbu Tsering known to all in Lhasa as ‘Laba’ (or the lover!), escaped from a Chinese labour camp near Lhasa, and arrived at Kalimpong. Local opera fans there decided to set up an opera company with Norbu Tsering as the master. A few other Kyurmulung performers, Phurbu Samdup and Tsering (according to Norbu Tsering) then living in Kalimpong joined this new company. I clearly remember two Kyurmulung children, Shilog and Namgang Lhamo, who occasionally performed with them, but who were later enrolled in the Tibetan Central School in Kalimpong.

According to my friend Tashi Tsering la at least two other exile opera troupes seemed to have been organized in the early sixties: one from among the members of the Tibetan Handicraft Center in Dalhousie in East Punjab (later Himachal Pradesh), the other from the road-workers of the Chamba Road Camp Group (or Champa brgya-shog) also in East Punjab.

In Kalimpong, the opera company was able to obtain on loan, the elaborate (and expensive) costumes from the aristocratic house of Yabshi Phunkhang (Phunkhang). The head the Phunkhang family, the late Gonpo Tsering was married to a princess of the Sikkim royal family, and had managed to transfer much of his family posessions to Sikkim. This company also performed in the neighboring city of Darjeeling for the Tibetan community and schools. Around this time, the first detailed ethnological study of this Ache Lhamo company was conducted by the American scholar, Jeanette Snyder.

In 1965 Phuntsok Namgyal Dumkhang was appointed director of the Music, Dance and Drama Society in Dharamshala. He had served as a junior official in the old Tibetan government and had also studied in China. More importantly, he was a talented musician and a creative director. He persuaded the opera performer, Norbu Tsering and other performers from Kalimpong and Darjeeling to join the official Drama Society in Dharamshala. It was during Dumkhang’s directorship that the opera was first performed. Two scripts, The Goddess Dowa Sangmo (mKha’-‘gro’i bu-mo ‘Gro-ba bzang-mo), and The Celestial Maiden Sukyi Nyima (gZugs kyi nyi-ma) were successfully produced.

Though the Dharamshala public thoroughly enjoyed the performances, some people questioned whether the tradition of the Tibetan opera should be revived at all. In the early and mid-sixties the Dalai Lama and the Tibetan community-in-exile went through a somewhat ill-informed and muddled modernization period. I was told by the Secretary of the Drama Society, Tenzin Gyeche Tethong, that some Tibetans argued that the revival of the opera represented a reversion to former feudal and aristocratic ways. On the other hand, Dumkhang was also criticized by conservatives and opera purists for making some small changes in costuming, which he had done in the interest of realism. Dumkhang’s innovations in opera and also in other areas of music and dance were, on the whole, successful. He resigned as the director of TIPA in 1968.

I joined the Drama Society in the March of 1969, essentially as an English teacher, though I was soon involved in helping out with the productions and also playing the dranyen lute for the dance performances. The departure of Dumkhang and other senior performers had demoralized the remaining performers, and it was an enormous task for the new director, Ngawang Dhakpa, and the Secretary, Tenzin Gyeche, to keep the organization functioning, far less attempt radical innovations. Furthermore, living conditions at the Drama Society were grim, and quite a few of the performers were anemic and suffered from tuberculosis.

When I joined, the Society was then only performing propaganda plays, folk dances and so called “historical plays” which were rather wooden dramatizations of Tibetan history, interspersed with song and dance routines that seemed jointly inspired both by Chinese opera and by the musical routines of Hindi films. In fact Tenzin Gyeche once timed all the sequences of a ‘historical play’ and discovered that nine-tenths of the show was taken up by the dance routines and only one-tenth of it was, strictly speaking, actually about history. It was also performed indoors on a proscenium stage with crudely painted sets. But in all fairness it must be said that the Tibetan public hugely enjoyed these colorful shows, which also served as an effective morale booster to the refugee population and as an elementary history lesson on Tibet’s glorious imperial past.

Tenzin Gyeche and I were against the continual performances of the ‘historical plays’ and wanted traditional operas to be revived again. When the talk came up again of opera being feudal, we tried to explain that even in such developed nations as France and Germany, opera was not only performed but regarded as the premier classical performing art; and that even in the Soviet Union traditional opera and ballet was supported and encouraged by the state. It was only in Communist China that traditional opera, besides almost everything else of China’s ancient culture, was being systematically destroyed.

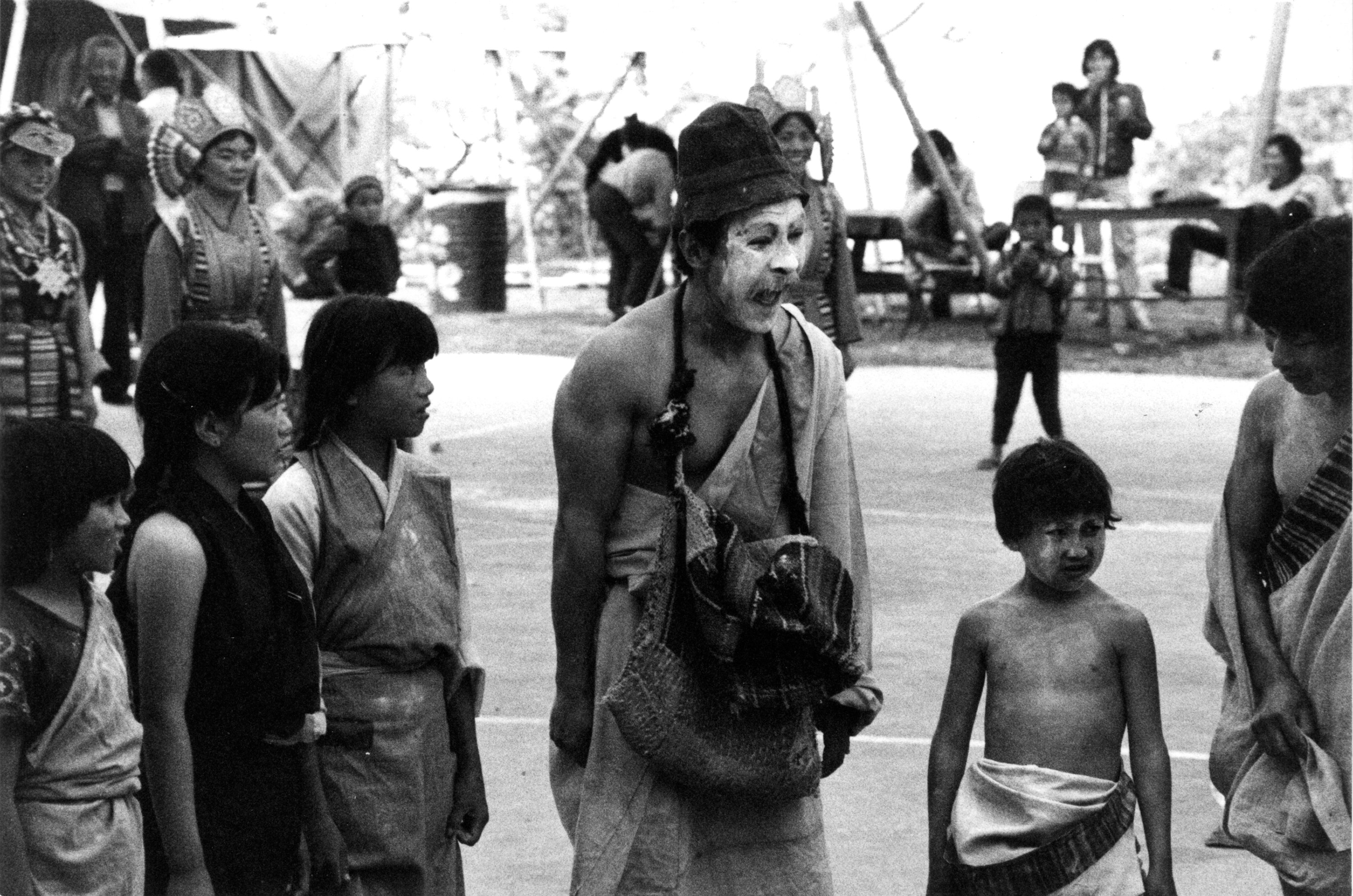

All the artistes at the Drama Society were keen on performing opera again, as much as the Tibetan public was keen on seeing and enjoying it, as it soon became apparent. The ‘progressive’ criticism of opera was by this time clearly limited to a very insignificant minority. A especially enthusiastic opera revivalist was the old opera master at the Drama Society, Gyen Dorjee, who had in the past been a member of the Chungpa company from the district of Chung Riwoche in Western Tibet. The Chungpa had been the Thirteenth Dalai Lama’s favorite company. We chose the story of The Celestial Maiden Sukyi Nyima, which is held to be the Tibetan adaptation of the great Sanskrit classic Shakuntala, by Kalidasa, which was much admired by Goethe. The Drama Society already had the costumes and the musical instruments necessary, so in a fairly short while, around the spring of 1970, we had a performance ready. My inability to sing opera arias did not prevent me from playing the role of the village idiot in the story. I should also emphasize how very small my own contribution was to this revival. I am sure the Drama Society would have performed opera sooner or later. I, in my impatience, pushed them to do it a little faster.

My new-found interest in Tibetan opera prompted me to interview various experts in the field. I conducted a long interview with kungo Liushar (sKu-ngo sNe’u shar), the retired Foreign minister of the exile Tibetan Government, who was regarded by some as an expert on opera, particularly on the tradition of the Gyangara (rGyal-mkhar-ba) company. This troupe of mainly monk performers was especially appreciated by the true opera connoisseur for its restrained performance and classic singing style. Kungo Liushar was emphatic that the Drama Society had to revive the Gyangara style and in particular the romantic classic, The Story of Prince Norsang, which is derived from the Sudhana Jataka, one of the stories of the former lives of the Buddha. The problem was that all the performing scripts (‘khrab-gzhung) had in the past been kept in the Treasury Office in Lhasa, and, no one had managed to bring out any to exile. The printed biographies and historical accounts on which such scripts were based could be obtained in Dharamshala, but the performing scripts are quite different from their original sources. In the case of Norsang, the play is only a specific selection (the second half) of the story. This particular jataka story was novelized by the Tibetan writer, Dingchen Tsering Wangdu (sDing-chen Tshe-ring dbang-‘dus) in the 18th century. The novel itself was available in print, but adapting the performing script from the novel was a major task.

Another additional problem was that not a single member of the Gyangara Company had made it to exile. But Drama Society director Ngawang Dhakpa remembered that there was, in Dharamshala, a retired government official, who had formerly been a disciplinarian (chab-dam) of Drepung monastery and a great opera fan, particularly of the Gyangara school. This person, chab-dam Ugen (O-rgyan), had even organized a troupe from among the refugee community in Dalhousie in Northern India, and had personally performed before His Holiness the Dalai Lama. So an informal committee was constituted with Ugen, the opera master Dorje, director Ngawang Dhakpa, senior performer Phurbu Tsering (Phur-bu tshe-ring) and myself.

Gradually a performing script was put together. Getting people to remember the melodies for the songs was harder. It was like assembling a jigsaw puzzle from the memories of various people. Kungo Liushar, the retired foreign minister, contributed the tunes to some arias. My mother, Lodi Lhawang, knew the ghop-sol (go-gsol) arias sung by Prince Norsang’s mother, the queen, to consecrate his suit or armour, sword and helmet, before Norsang departs for battle against the ‘Wildmen’ of the North. She had been taught these as a young girl of fourteen or fifteen at Chamdo by the famous opera connoisseur and expert kungo Mindrukbu (sKu-ngo sMon-grub-sbug).

At the Drama Society in Dharamshala, Chab-dam Ugen contributed the bulk of the melodies, information and memories for this revival of Norsang. By this time we had also managed to get the former opera master Norbu Tsering to visit the Drama Society from his new home in Bylakuppe, South India, and he joined in our efforts and provided much help and direction.

My small contribution to the forthcoming performance of Norsang was in the making of suits of fake armor, helmets, shields etc., for Norsang and his warriors. I also started work on the construction of a small Greek style open-air amphitheater on the hillside behind the Drama Society grounds. Tibetan opera is usually performed in the round, but suffers from the fact that most scenes are played facing the front. So it is not true theater in the round. I felt that a workable compromise would be a Greek style open-air amphitheater with the audience seated on three sides, with every next row of seats slightly higher than the one in front. Acoustically, there would be an advantage as the singers would generally be facing the audience, and I intended to erect a curved reflecting surface at the back of the stage. Everyone at the Drama Society put in a couple of hours labor every day for six months. But this was one experiment that was not too successful.

In 1971, before the end of the construction of the amphitheater and the premiere performance of Norsang, I was obliged to leave the Drama Society to join the Tibetan resistance force in Mustang in Northern Nepal. I must mention one opera-related incident in my life at Mustang. One day I made the discovery at our headquarters of a set of opera costumes and masks. On inquiry I was told that the soldiers had in the past performed opera (Dowa Sangmo, to judge by the costumes) on certain holidays and ceremonies, but that the tradition had died out. The connection between the Tibetan military and opera is not unusual. For instance, the commander of the victorious Tibetan forces at Chamdo in 1918, had the opera Sukyi Nyima performed for the entertainment of the troops and the populace as well as the British peace negotiator, Eric Teichman. The performers were all soldiers. In September 1904, after the Younghusband expedition forced its way into Lhasa, a treaty was signed at the Potala between the Tibetans and the British. At the conclusion of the ceremonies the opera Kiu Pema Woebar (Khye’u Padma ‘od-‘bar) was performed for the entertainment of the British officers.1

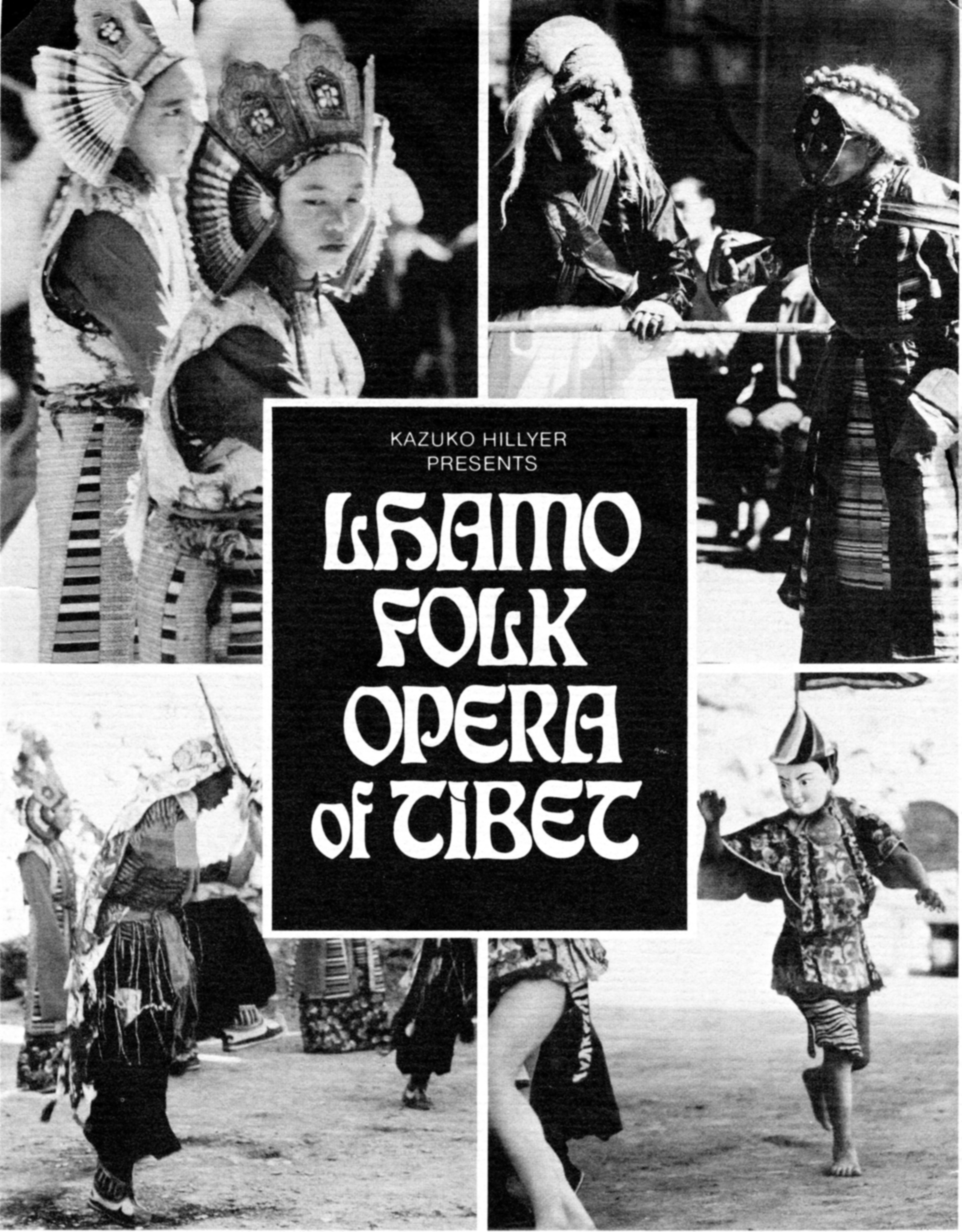

In 1975, I was appointed as manager of and spokesman for the Drama Society on their first international tour of the USA, Europe and Australia and Singapore. The first presentation of a Tibetan opera in the West took place in the summer of 1975 at the Volkshaus in Vienna, where Mozart’s Magic Flute had its premiere performance. We put on the story of Kiu Pema Woebar (The story of the previous incarnation of Guru Padmasambhava). On this tour the Drama Society had two programs that sponsors or theaters could chose from. One was an abbreviated but complete two-hour performance of Pema Woebar, while the other, “Dances From the Roof of the World” contained a few excerpts from the operas Sukyi Nyima and Dowa Sangmo.

In the autumn of 1980, I was requested by Drama Society artistes and the Secretary of the Council for Tibetan Education of the Tibetan government, Rikha Lobsang Tenzin, to become the director of the Drama Society. I started work in December that year though my official appointment was from January 1981. On assuming this responsibility I was immediately involved in a controversy involving the opera. In the spring of 1981, I, as director of the Drama Society, attended the Annual General Meeting (lo-‘khor sri zhus las-bsdoms tshogs-‘du) of the Tibetan government, attended by all members of Assembly of Tibetan People’s Deputies, the kashag (bka’-shag), all senior government officials, heads of resettlement camps and various institutions, and even independent political organizations as the Tibetan Youth Congress and the Four Rivers Six Ranges.

At the meeting, a member of the Assembly of Tibetan People’s Deputies, Tsering Gyaltsen, representing the Nyingmapa sect, raised objections to the way opera performers poked fun at religious institutions. He specifically objected to the scene from the opera Prince Norsang (Chos-rgyal Nor-bzang) where an itinerant priest (a-mchod) is shown dozing when conducting services, and also surreptitiously stealing and eating sacrificial cakes (torma). Another member of parliament, Amdo Chone Chaypa Alak Jampel, (A-mdo co-ne mched-pa a-lags ‘Jam dpal) a Gelukpa incarnate lama, also expressed his strong disapproval of the comic scenes in the opera Sukyi Nyima where an oracle is depicted as inebriated and uttering nonsensical prophecies; and also another scene (from the same opera) where monks and nuns are shown as quarreling and finally coming to blows over the offerings made by sponsors.

I replied that opera performers had been performing such satires and making such irreverent jokes even in the old days, and that I would certainly not stop this democratic tradition in our performing culture. One of the two MP’s denounced me as an ‘unbeliever’ (chos la dad-pa med-mkhan). I jokingly replied that if Buddhists were now becoming so intolerant I would probably convert to Islam. The following days of the Annual General Meeting, I (somewhat facetiously, in retrospect) signed the attendance register as Abdul Norbu. The two MP’s were furious with my disrespectful attitude and a heated exchange took place. Finally, the chairman of the Annual General Meeting, Lodi Gyari, who was vice-chairman of the Assembly of Tibetan People’s Deputies, stepped in and put a stop to the dispute, which was getting fairly ugly. Some of the older people at the meeting, especially those from Lhasa, who disliked anyone messing with their beloved opera, gave me moral support. One of them was chab-dam Ugen, who in 1970, had helped us to revive and stage the opera, Norsang.

But as they say in Lhasa, it doesn’t pay to cross opera performers. The secretary of the National Working Committee, kungo Jangtay Phuntsok Wangdu, had earlier requested the Drama Society for an opera performance at the conclusion of the Annual General Meeting. The opera master, performers and I decided on the play Prince Norsang and made some subtle script changes in the greater interest of free speech and cultural preservation. In the scene where the rascally itinerant priest, Black Hari, makes his appearance, we managed to interject some pointed observations about the intolerance of certain members of the Assembly of Tibetan People’s Deputies. The public enjoyed the joke, and the kashag ministers who were themselves often the victims of the Assembly’s criticism were observed to be having a good laugh at the expense of their erstwhile critics.

In one new scene the itinerant priest Amchoe Hari Nagpo, faces a predicament about what religious service he could perform without offending one sect or the other. He first decides to recite the Vajra guru mantra, but then one of the royal servants rushes over and claps his hand over the priests mouth, telling him that the Nyingma sect would take offence at a rascally priest like him reciting this mantra. Amchoe Hari then decides to recite the Dmigs-brtse ma prayer, but the king’s servant tells him that the Gelukpas would not like it. And so it went on, till the priest realizes that regardless of what he does some Buddhist sect would find it offensive. Exasperated, the old priest decides to play it safe. Vigourosly ringing his drilbu bell and rattling his damaru drum , he launches (dance and all) into the swinging Bombay film song Dil Deykay Dekho “Give (your) heart and look”. A decade later, the anthropologist, Dr. Marcia Calkowski wrote of this incident in the American Ethnologist. 2

In spite of such obstacles we managed to bring about a small renaissance in Tibetan opera in the next five years. My first task was changing the name of the Tibetan Music, Dance and Drama Society to that of the Tibetan Institute of Performing Arts, or TIPA, as it is now generally known. At the beginning of my tenure TIPA faced enormous problems. Many performers suffered from tuberculosis, caused in part by malnutrition. Furthermore, traditional prejudice against actors and musicians, a throwback to medieval times, still prevailed, right up in the highest levels of Tibetan society, which affected the morale of performers.

The main sticking points was funding. At that time, aside from Tibetan Buddhism, there was little interest in Tibet and Tibetan culture internationally. What little humanitarian attention Tibetan refugees received was largely confined to the plight of children, especially at the Tibetan Children’s Village. The Tibetan government itself was desperately strapped for cash, though a year later I was able to lobby the cabinet and the Assembly of Tibetan People’s Deputies to raise (in fact double) the salary of all artistes. I was given great support in this by the late Riga Lobsang Tenzin, Secretary of the Council for Tibetan Education, who was an enthusiastic and staunch supporter of TIPA.

We also published a newsletter Dranyen (which is what the Tibetan lute is called, and which literally means ‘melodious sound’) and started a ‘Friends of TIPA’ program which bought in some donations from abroad. One of our main supporters was Mrs. Anne Jennings Brown of Britain, who not only worked at TIPA for a couple of years but also raised funds for us abroad. Among the many who donated to TIPA I should mention the late Hugh Richardson, the last British representative in Lhasa, who besides some generous financial donations also sent us the original copy of the lyrics of the ceremonial songs of “Bras bu gling nga” sung at the Potala on New Year’s Day, which he had, long ago, received from the chief clerical office (Yig-tshang las-khungs). Mr. Richardson also contributed a wonderfully evocative article on the Lhasa Opera Festival for our publication Zlos-gar: The Performing Traditions of Tibet (Dharamshala, Library of Tibetan Works and Archives, 1986).

Gradually, we managed to overcome many of our difficulties. Let me elaborate on those specifically having to do with the opera. To make our artistes more focused and their performances more dynamic, we resorted to a variety of schemes, a few of which turned out surprisingly effective. We made it mandatory for every TIPA member, including staff and director, to participate in a daily half-hour of prayer and meditation in the morning, during which an invocation and prayer dedicated to Thangtong Gyalpo the patron saint of Tibetan opera was chanted. This special prayer was unearthed for us by the eminent Tibetan scholar Tashi Tsering la, who also helped us with much of our research work in opera and other performing traditions.

We also built a ‘Temple of the Performing Arts’ with statues of Buddhist deities, saints and lamas related to the performing arts: Sarasvati (the Indian goddess of the arts), Padmasambhava (tantric dance), Milarepa (singing and composition), Sakya Pandita (treatise on music), and the Sixth Dalai Lama (romantic songs). Of course, we also had an image of the Buddha and the Bodhisattva Manjusri. The centerpiece was a large statute of Thangtong Gyalpo. All these images were housed in a detailed three-dimensional representation of the Tibetan landscape featuring mountains, wilderness, pastoral and agricultural scenes. The Potala palace, a monastery, a town, a merchant caravan, the Tsangpo river and a chain suspension bridge provided detail and specificity to this miniature Tibetan world. Tiny models of every conceivable Tibetan animal, real and mythical, were present in this representation. One of the intentions of this temple was to provide younger TIPA members with a detailed and captivating image of their lost homeland. The concept and initial design was mine but the actual execution of the project was entrusted to TIPA’s master sculptor and mask-maker, U Kalsang of Kongpo. The ‘Temple of the Performing Arts’ attracted visitors and worshippers in its own right. It also inspired a few imitations, most notably that at the Norbulingka Institute in Dharamshala.

Formal acting classes were now added to the training routine at TIPA. Traditionally, only singing lessons had been a part of the performer’s curriculum. To broaden the theatrical knowledge of our artistes, we managed to obtain films of other performing traditions of the world, and also documentaries on such great mime artistes as Marcel Marceau.

We did not want to bring about too many major changes in the simple traditional staging of the performance, but added a low platform in the center of the stage, for some spatial variation in the positioning and movement of actors. To create a culturally authentic visual experience for the audience we made absolute sure that all items and props used on stage were genuinely Tibetan. For instance it is customary for performers to sometimes take a drink on stage especially if the day is hot and he or she has a number of arias to sing. We made sure only traditional drinking vessels were used. We also started a project to locate and purchase such traditional household articles, as bowls, cooking pots, ladles, bags, yak-hair ropes, travel-chests, saddle-bags and so on, all of which were also intended to be used later for exhibition at a planned Museum of Folk Culture at the Institute.

One major project for our opera “renaissance” was the recreation in 1982 of the giant canopy ‘Floating in the Sky’(bya-g.yab nam-mkha’ lding) that used to cover the large stone-flagged stage at the Norbulingka palace in Lhasa during the annual opera festival. This vast white canopy, decorated with traditional auspicious symbols, shaded not only the stage but a large part of the audience as well. Donations for the canopy came from individuals and small businesses in Dharamshala, the main amount coming from the late Dr. Lobsang Dolma. Another Norbulingka-inspired feature was in decorating the stage with flowers. During the opera festival in Lhasa there would be, on stage, an informal exhibition of flowers from the palace gardens. The Norbulingka gardeners would change the potted plants every day of the festival. At TIPA we helped senior artistes and families to cultivate flowers in their spare time, which were displayed during the opera performance. This little innovation probably contributed to the nostalgia quotient of the audience, but even otherwise seemed to enhance the fairly-tale atmosphere of the show.

Costumes and jewelry were a problem, because, as far as possible, they had to be genuine. Substitute costume material as tinsel, chintz, cardboard, etc., that could pass muster under artificial lighting, were quite unsuitable for performances in daylight, especially with the audience sitting up close as is the case in opera performances. His Holiness had, in the sixties, donated a number of expensive costumes for the main characters, but most of the others were made in TIPA itself where we had a costuming designing and tailoring section. We discovered that the special brocades and silks needed for certain costumes were manufactured by firms of Indian silk weavers in the city of Varanasi, which had old commercial ties to Tibet. In the matter of masks, which are crucial to Tibetan opera, we had the assistance of gifted craftsmen from Nechung monastery and the Gyuto monastery. Our own mask-maker U Kalsang, made the spectacular papier-mâché demon masks for the opera Pema Woebar, among others. The master thangka painter, the late Jampa Tseten, an absolutely loyal (and regular) opera goer, also contributed enormously over the years by painting costumes, masks, props etc., for us.

One of the major problems we faced was finding a good quality opera drum, the shell of which is wooden and has special acoustic properties because of an extra inner space that is scooped out of the wooden shell. Tibetans believe that this gives the drum a special depth in tone and can further project sound better. No such traditional drums were available in India. Even the Dalai Lama’s personal monastery had been forced to use Indian army snare drums with copper shells. But the tone of these drums was too flat and lacked depth. Though we looked around it proved impossible to find a traditional drum-maker from Tibet. Finally, through the help of the kashag minister kungo Tsewang Tamdin, who had formerly been a steward to the Sakya Lamas, we located a professional drum-maker U Lhakchung from Grum pa, and we finally got our drum. The appearance of a skilled drum-maker at TIPA gave me an idea.

There is an un-stated but quite firm rule that no musical instrument other than a drum and a cymbal be used during an opera performance. I reasoned that I could stick to this rule but modify it to enhance the expressive and dramatic qualities of these instruments. I had three different size drums made. The largest was about five feet in diameter, the next about two and a half feet, the size of the normal opera drum, while the smallest was only about a foot and a half in diameter. All three drums were mounted on a special frame and the drummer was required to use two sticks to play them. I did not want to overwhelm my drummer and initially only required him to use the different drums to play specific tattoos for different characters: the big drum for important or villainous characters, the small drums for comic characters and so on. I thought that over time we could develop this in complexity and depth. I also managed to put together matching cymbals to complement the drums. There is a historical precedent for such experimentation with the opera drums.

In 1922, a year before the 6th Panchen Lama fled Tibet for China he had the Chungpa company from Chung Riwoche in Western Tibet, perform the opera Chung Donye Dhondup (gCung Don-yod Don-grub), the Brothers Dhonyo and Dhondup, at the annual ‘Great Spectacle’ (gZigs-mo chen-mo) performances at Tashi Lhunpo monastery. During the scene when the elder brother carries his dying younger brother across a terrible wilderness, there was, according to an informant, not a dry eye among the spectators. Some in the audience even had a premonition of impending tragedy. The sense of foreboding seems to have been heightened by an innovation of the stage manager who had the drummer rub a little honey on the palm of his hand and then run it across the surface of a giant drum. The resulting friction created a faint rumble, like that of distant thunder.

One of the most important decisions we made at TIPA was to put together one old opera script every year and to perform it. We managed through research work and committee discussions, as I have described before, to put together two scripts in 1982. One was the historical play Gyasa-Belsa, (rGya-bza’ Bal-bza’), The Chinese Princess and the Nepalese Princess, the story of how the Emperor Songtsen Gampo’s wily minister Gar Tongtsen triumphed over all contenders at a trial of wits to win the hand of the Chinese princess for his emperor. The other play was Nangsa, a true account of a beautiful and deeply spiritual woman who dies from being abused by her husband, a feudal lord, and his family. She returns from a sojourn in the netherworld to make her tormentors see the errors of their ways and devote themselves to a life of religious practice.

We also recreated in 1981, the Shoton or the annual Opera Festival that took place in Lhasa before 1959. We staged the introductory performances of all the various opera troupes that attended the festival, and even put on the cham dances of the Karmashar oracle and his entourage, that was performed on the first morning of the opera festival at Norbulingka.

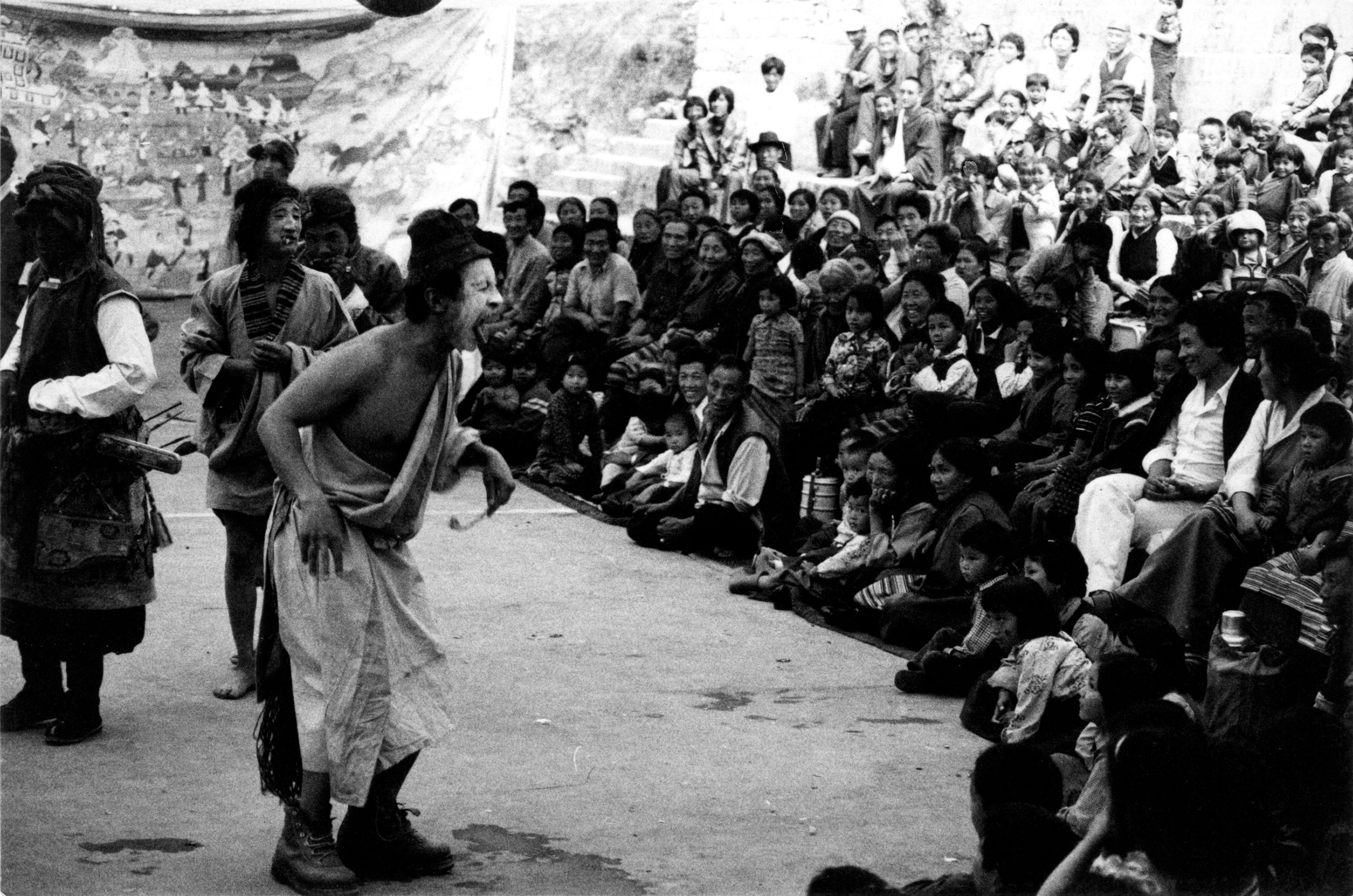

In 19813, I got the idea of writing a completely new opera for TIPA. The story I chose was the legendary account of how Tibetan opera had been started by the great sage Thangtong Gyalpo as a vehicle of public entertainment and education, and also a means of raising resources for his bridge-building activities. I chose as the main characters two humble pilgrims, a Khampa chagtsel lama (phyag- ‘tshal bla-ma), a pilgrim who prostrates the length of his journey, and the other a devout Amdowa accompanied by his donkey, who meet on the trail to Mount Kailash and become friends. They encounter many difficulties: bandits, a raging river and rapacious ferrymen. Ultimately they are helped by Thangtong Gyalpo who convinces them and all the local people of the area to join him in the construction of a chain suspension bridge that would not only benefit all people but even animals as well. More trials follow with local demons sabotaging the project, but in the end Thangtong Gyalpo and his new-found disciples overcome all odds to build the first chain suspension bridge in Tibet.

Norbu Tsering worked on adapting certain melodies from other opera arias to the new lyrics of this opera, which we called Chaksam (lCags-zam, The Iron Bridge).

The Tibetan opera is frankly Lhasa-centric and unapologetically mediaeval in its outlook. All the main characters are invariably depicted in the costumes of the Lhasa aristocracy. Even the eponymous heroine of Nangsa, who is unquestionably from Gyantse in Tsang province, is always shown wearing the headdress and jewellery of a Lhasa, and not a Tsang, aristocratic lady. Villains and buffoons are usually depicted as people from outlying regions and provinces of Tibet. Khampas are invariably represented as executioners and hunters. The malicious gossip and poisoner in Sukyi Nyima is a Kongpo woman (the poison-cult is said to be widespread in Kongpo). The hag witch-servant in Dowa Sangmo is a Tsang woman. The Wild Ape-Men (migou) of the North in Norsang are dressed as nomads, though the nomads of Pemachen, in Dowa Sangmo, are presented in a more positive light. Mutikpa or heretics (actually members of a Hindu sect in the original story) in Pema Woebar are nonchalantly represented as Tibetan Muslims with their dranyen lutes and typical exclamations “Khuda Kasam, Bhai-la”. (I swear by Allah, O brother). People from Amdo are completely ignored in the opera. Only in exile, and even there only in the concluding and customary sertri ngasol, the “coronation or installation of the golden throne” scene, does an Amdowa make a brief appearance as a representative of one of the “Three Provinces of Tibet”, a post 1959 political construct.”

Of course, operas world over, with the exception, perhaps, of The Marriage of Figaro, are not vehicles for egalitarian or revolutionary sentiments. Still, I thought that it would be nice to have at least one opera where a humble Tibetan layperson from outside Lhasa, was the principal character. So in Chaksam I created these two lowly pilgrims, one from Kham and the other from Amdo, so poor that they cannot pay the one tramka ferry ride to cross the Kyichu river. The peasants of the village of Chushul (where the Kyichu meets the Tsangpo river) are also celebrated, and among them the village blacksmith, Achung, who forges the iron chains of Thangtong Gyalpo’s first suspension bridge. The traditional prejudice against blacksmiths is still prevalent in exile Tibetan society. I certainly did not intend to emulate the heroic proletarian spirit of Madame Mao’s revolutionary operas and our two pilgrims, Achung, et al., are depicted as human, fallible and often absurd. They are only heroic in the sense that they, like most other Tibetans, seldom lose their good humour, their faith and their humanity even when overwhelmed by life’s travails. When knocked down all they require is a little tsampa, some meat (on bone), a long swig of chang, a prayer to the gods, and they’re back on their feet again.

One other feature of my opera, The Iron Bridge, was its didactic quality, not just in the moral of the story but in the details of the production. I used the opera as a vehicle to teach children and youth-in-exile how Tibetans lived and did things in the past. For instance, the kind of traditional camping gear: willow pack-frames, saddles, blankets, bellows, folding ladles, and cooking pots that were used by old-time travellers. Also how farmers worked in the fields, what equipment they used, and how Tibetan blacksmiths worked metal. I would like to stress this educational aspect of our performances because the opera was hugely popular with children. TIPA regularly performed operas for the Tibetan Children’s Village in Dharamshala, and the response was overwhelming. Small children would sit on the ground the whole day in rapt attention. Generally small groups would gather around one child who knew the story and who explained the scene to others. Their involvement in the story would be total. For instance, in the scene from Nangsa, where the eponymous heroine is beaten by her husband and tormented by her sister-in-law, I often noticed that children would be in tears, as would older women in the audience. Performing for children was always a very rewarding experience.

After the success of this opera I made plans, and even got so far as drafting a ‘treatment’ for an opera on the life of the great Tibetan yogi, Milarepa. But I had to leave TIPA in 1985 before I could carry out the project. I am glad to say that performers and staff at TIPA managed to write and produce this opera some years later.4

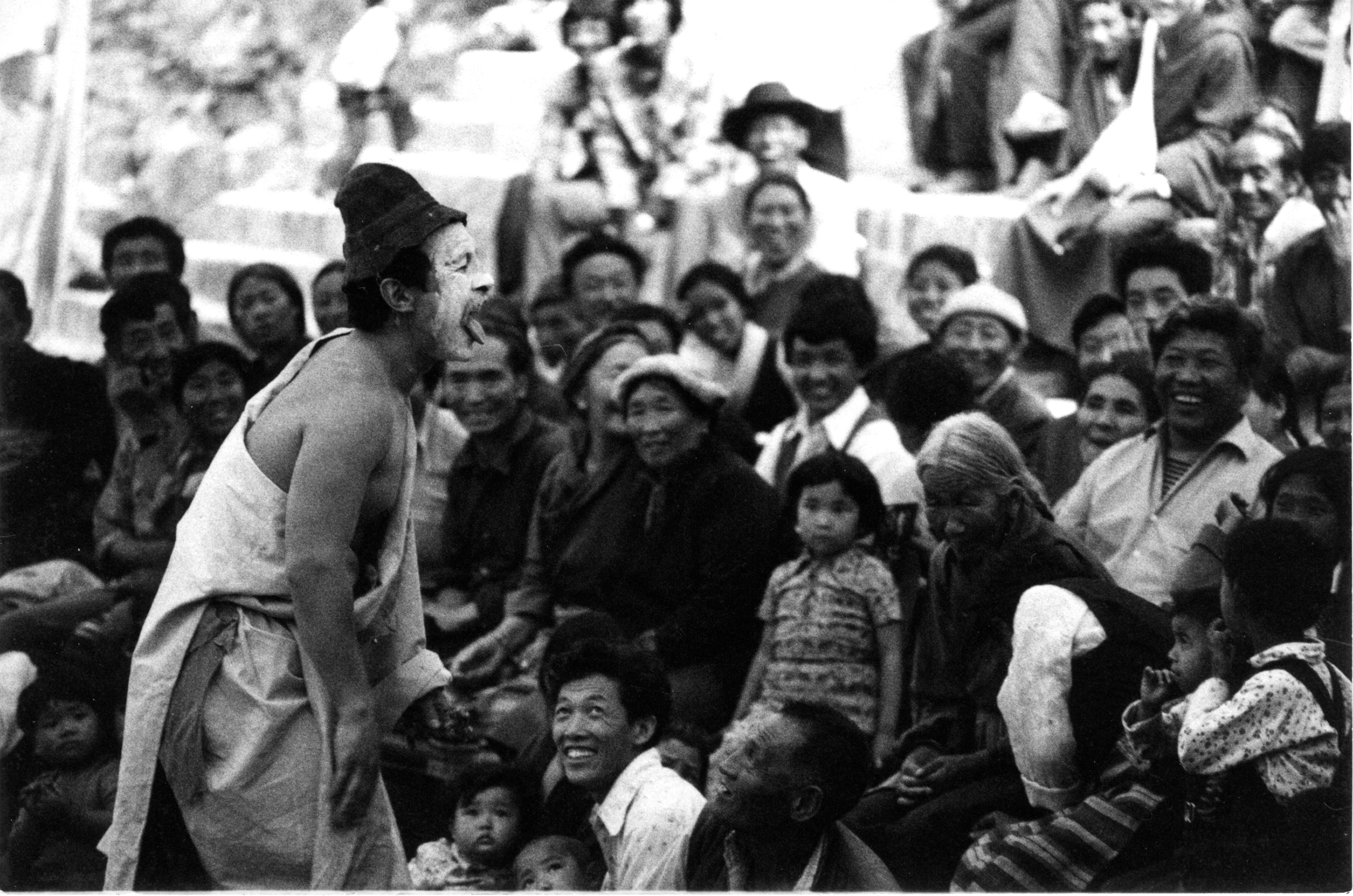

To ensure that the opera was not just entertainment for children and older folks, we worked to improve production values in every aspect of the performance. For instance in the old days the comic scenes would be broad, often repetitious and generally unrehearsed. Though we allowed some spontaneity, we started to script and rehearse the comic scenes, and sometimes provided them with a satirical bearing on contemporary political events and social mores. This proved a big success with the audience and also gave the opera a cachet with the younger and more educated segment of Tibetan society. We also tried to emphasize certain star quality performers, and very soon there was a response, in terms of fan letters and so on, from younger members of the audience.

In nearly every aspect of Tibetan opera, in the staging, musical accompaniment, costumes, choreography, comedy and production values we made definite improvements over traditional staging of the opera. Yet in one aspect, the singing, we were unable to make a full breakthrough. The general consensus among connoisseurs was that the opera singing in TIPA was uniformly good, but that we lacked the brilliant, star quality voice, which I was assured, was not all that unusual in old Tibet. Otherwise even the sternest conservative opera fan agreed that TIPA performances were as good, if not better in terms of production values and staging, than performances at the Opera Festival in Lhasa, in the old days.

The public, in Dharamshala and other Tibetan settlements and centres where we toured, loved the opera performances, and TIPA’s opera season became an important fixture in refugee social life. We tried to infuse the actual production and also the surroundings with a rich pageant like feel, not only with the Tibetan style canopy and flower exhibition as mentioned earlier, but also by the use of traditional decorative banners and hangings. Our emphasis on authentic costuming not only applied to performers, but extended to musicians and stagehands as well. Even I as the director (in full traditional regalia) was inducted in a solemn ceremony at the beginning of the festival where Thangtong Gyalpo’s statue was installed on a throne on the stage and offerings made of incense, khatags and and a length of iron-chain. A carnival like atmosphere was also created with a variety of Tibetan food-and-beverage stalls and sales of paper opera masks for children. We also encouraged families to bring picnic lunches and drinks and even erected a few park-style picnic tables and benches, though most Tibetan preferred sitting on rugs on the ground. Overall, we managed to produce not only good entertaining traditional opera, but were also somehow able to recreate a bit of the ambience of old Tibet in the lives of Tibetan exiles. And they fell in whole-heartedly with our sentimental design, as I mentioned in an article in Du, the Magazine of Culture, (Switzerland) July 1997:

If some spring evening you were to take a walk up the mountain road from McLeod Ganj to the Tibetan Institute of Performing Arts you might come across cheerful groups of men and women proceeding rather unsteadily downhill. They will probably be clinging to each other in boozy camaraderie, helping to prop each other up. They will all be singing — at the top of their voices — a peculiar yodel-like air. These people are returning from a day long performance of the Tibetan folk opera, LHAMO, a theatrical form that combines the relaxed informality of village cricket, the magical world of pantomime, and the open-air eating and drinking of a good picnic.

Inside Tibet opera began to make a tentative reappearance in the early eighties. After the unsuccessful uprising of 1959, the Chinese authorities had not immediately banned the traditional opera, but allowed it to be performed during the visits of dignitaries and guests, especially foreign ones. For instance, in 1961 on the visit to Tibet of a left-wing British journalist, Stuart Gelder, 5 a traditional opera was performed. Gelder depicts some sequences from a performance in the documentary he shot. In the centre of the stage where usually the image of the patron saint of opera is placed, can now be seen a portrait of Mao Zedong. But the gradual suppression of traditional opera (xiju) in China itself, a couple of years later, ensured that Tibetan opera would soon be proscribed.

With the advent of the Cultural Revolution no traditional performance of any kind was permitted. In fact, the only performances allowed were the eight or so revolutionary operas approved by Madame Mao. This stricture held even in Tibet where in the late sixties at the Songjoe Ra(gSung-chos rva-ba), the main square behind the Jokhang temple, where the Dalai Lama would give his annual post-New Year sermon, the revolutionary opera/ballet The White Haired Girl (Baimao nü) was performed.

But from the 1980s, with the advent of Deng’s so-called liberalisation policies, the official Performing Arts Troupe in Lhasa began to perform an officially approved version of Tibetan opera. The singing voices were changed to sound somewhere between the “meowing and shouting” (André Malraux) of Beijing opera, and the classical European style introduced by the Russians to China. Traditional scripts were rewritten in order to conform not only with official ideology but also Chinese interpretation of Tibetan history, as in the traditional opera, The Chinese Princess and the Nepalese Princess (Gyasa-Bhelsa), now called Princess Wencheng, after the excision from the story of the inconvenient Nepalese Princess.

Ideological changes could also be observed in the play Nangsa, traditionally the story of a pious village girl forced to marry the son of a powerful feudal lord. Nangsa is abused in her new home and dies, but because of her piety is sent back again to the world of the living by the Lord of Death, Shingje Chogyal (gshin rje chos rgyal). At the end of the story she attains liberation and makes her husband and in-laws see the error of their ways. The Chinese director of the Tibet Opera Troupe, Hu Jin’an, changed the story to one of class conflict. Nangsa returns from the dead to denounce her husband and in-laws in the approved Communist ‘struggle’ (‘thab ‘dzings) manner. Then brandishing a large broadsword she proceeds to murder them one by one. The acting and dancing style was also speeded up and ‘modernised’ that it seemed to be a deliberate parody of a Tibetan opera. 6

These performances were not popular with most Tibetans. In 1978, a group of former opera lovers from the small village of Zhol below the Potala, set about reviving the authentic Lhamo tradition. A friend of mine, Lhasang Tsering la, was in Lhasa in 1980 and attended one of their public performances at the Norbulingka, the Dalai Lama’s Summer Palace. He informed me that some of the actors were very old and could not move that well, but that their culturally authentic show appeared to be hugely popular with the people of Lhasa. In fact, stories circulated in opera circles in Dharamshala that the master of the Zhol troupe was so old and weak that after singing an aria he would collapse on the ground and would have to be lifted up and supported to sing the next aria. I have been informed that such folk companies were later successfully organised in a number of villages and districts in Tibet. But this development is not within the purview of this paper, which deals with the revival of Lhamo in exile society.

In 1985, I was officially removed from TIPA. The main but un-stated reason was political, which I don’t need to go into in this paper, but the immediate cause of my dismissal had to do with a production related to the opera. My earlier opera Chaksam (Iron Bridge) had faced some criticism, mainly from local politicians, who charged that depicting a poor Amdowa accompanied by a donkey was insulting to the people of Amdo. In fact in the editor’s after-word to a history of Labrang, Amdo, 7 a young ex-monk, Hortsang Jigme (Hor-tshang ‘Jigs-med) who edited this book, makes a clear reference to this particular opera. He states that he was spurred to encourage the author to write this book to counteract such demeaning depictions of Amdo people. The donkey in question was (in the tradition of the English pantomime horse) merely two actors in a costume. Designed and made by TIPA’s master costume designer, Chime Dorjee, who I am certain had never read Winnie the Pooh, the finished product ended up looking remarkably like Eeyore.

In 1985, I revived this humble donkey in a new production of mine on the occasion of the Dalai Lama’s birthday. This tableau vivant, which was titled Lhasae Denlu (A Song in Memory of Lhasa), was inspired by the famous poem (of the same title) written by the Tibetan scholar/official Shelkar Lingpa in 1910, when he was living in exile in India, serving the Thirteenth Dalai Lama. In this production, the main scene is a busy market street around the Barkor area of Lhasa. The street is filled with richly dressed noblemen, ladies, lamas, Khampa merchants, ordinary Lhasa folk and a ten-man revue of dancing dranyen players. The musicians play a medley of popular nangma/toeshay tunes, the lyrics roughly corresponding to the happenings on the street. The humble donkey is shown carrying a load of firewood through the Barkor. The show was a big hit, but some weeks later, local Tibetan politicians in Dharamshala began to raise a furore, claiming that it was a deliberate insult to the Dalai Lama to trot out a donkey on his birthday celebrations.

After my departure from TIPA in November 1985, the opera tradition has been carried on by other directors, though certain problems have been created because of the apparent decision of the government-in-exile, to appoint as directors of TIPA only officials from within the ranks of the bureaucracy, with no background in the performing arts, and to exclude members or former members of TIPA from the selection. Furthermore TIPA’s autonomous status was revoked after my departure and the Institute was put under the Council for Religious and Cultural Affairs.

In 1986, prior to TIPA’s tour of the West, Kim Yeshe, an American woman connected with the Council for Religious and Cultural Affairs, appointed a Frenchman with some theatrical background to direct the Lhamo performance of Sukyi Nyima, that TIPA was preparing for its foreign tour. Overriding the protest of Tibetan artistes, a number of bizarre changes were made in the production. For instance, at the end of the opera when the celestial nymph finally meets her long estranged husband, the king, the couple were made to go into a romantic clinch, à la “Gone With the Wind”, in complete contravention not only of Tibetan opera conventions, but also of normal Tibetan behavior in public. Certain Tibet experts in the audience were reported to have raised protests. This Frenchman published an article on Tibetan opera in Choyang, 8 the journal of the Council for Religious and Cultural Affairs. The article made extensive and verbatim use of material I had published earlier in TIPA’s newsletters and in articles in the Tibetan Review, but did not once cite me as a source. He later claimed that the editors of Choyang told him to remove all such citations.

Some of the latest directorial changes in opera performances at TIPA have been those instituted by a young Tibetan performer/instructor recently arrived from Tibet, and trained by the Chinese. I happened to see one such opera where actors performed with the exaggerated stylized gestures — rolling of eyes, raising of eyebrows, etc., — characteristic of Chinese theatre. But such aberrations do not yet fortunately, seem to have completely taken over the traditional performing style. Of course, one cannot in all fairness, blame the young instructor from Tibet for such unhappy innovations. He was just doing what he had been trained to do. The fault lies in the Tibetan government’s repeated decisions to appoint as directors of TIPA only officials who have no knowledge or experience of Tibetan performing culture.

Besides the official opera company of the Tibetan Institute of Performing Arts, other opera companies have been organised in various other Tibetan communities in India and Nepal,9 that still maintain traditional standards. An opera company was even started in the Tibetan community in Switzerland, though I am not sure of its situation right now. One former performer and instructor of mine at TIPA, Tenzin Gonpo (bsTan-‘dzin mgon-po), now lives and performs in France. Last year I saw him give an incredible solo performance in Paris of the introductory ritual dance (‘don) and the concluding ceremony (bkra-shis) of the opera, normally requiring at least a dozen odd people. It was not only tremendously moving but a veritable tour de force.

The most successful and professional group outside Tibet or South Asia is “Chaksampa” (Builders of the Iron Bridge) in San Francisco, established by two former artiste/instructors of mine at TIPA, Shazur Tashi Dhondup and Sonam Tashi. This troupe has not only successfully managed to provide cultural sustenance to the Tibetan community in North America, but has even organised annual summer-camps to educate Tibetan children in opera and Tibetan performing culture. This troupe also performed at various American schools and universities. In spite of its relative success, the performers were not satisfied with their participation in ‘cultural events’ in the West. What they wanted most was to perform opera for a Tibetan audience; furthermore, an audience not only familiar with the nuances of the tradition, but one whose critical judgement they could respect and from which they could learn and improve.

This in a sense represents the overriding cultural problem Tibetans face now, not only with opera performers, but everyone else in the Tibetan cultural world. What is the extent to which one can successfully preserve Tibetan culture outside of Tibet? Yes, exhibitions of Tibetan sacred art, thangkas, bronzes and sand mandalas are now held regularly in major cities of the West. Tantric dances and sacred monastic music are readily available, recorded or live, to a Western audience, and also authentic Tibetan opera performances. That is, of course, all to the good. But what does this actually mean to the Tibetan and his personal cultural world? In order to truly survive, not only in museums, or in the accolade and admiration of foreign friends, Tibetan culture, especially performing culture must be able to entertain and inspire a new generation of Tibetans, and must have real meaning in the daily lives of Tibetans everywhere.

Notes:

1 This is reported in Macdonald, David, 1991 [1932]. Twenty years in Tibet. Intimate and personal experiences of the closed land among all classes of its people from the highest to the lowest. Gurgaon: Vintage Books, p. 39 [editor’s note].

2 Calkowski, Marcia S., 1991, “A Day at the Tibetan Opera: Actualized Performance and Spectacular Discourse,” in American Ethnologist, 18(4): 643-657.

3 See K. Dhondup, “A Bridge Long Ago,” in Tibetan Review, November 1981, pp. 9-10 [editor’s note].

4 See ‘Khrab gzhung zur ‘don dang/ ‘Khrab ‘khrid byed mkhan Blo bzang bsam gtan, Rnal ‘byor gyi dbang phyug chen po Mi la ras pa’i rnam mgur las lha mo’i ‘khrab gzhung du snying bsdus bkod pa, TIPA, Dharamsala, 1999 (Editors note)

5 See Stuart & Roma Gelder, The timely rain; the travels in new Tibet, Hutchinson, London, 1964 (Editors note)

6 See [Jamyang Norbu], Art and propaganda, Dra-nyen; Newsletter of the TIPA, Dharamsala,1984, vol.8,no.1, pp.31-36 (Editors note)

7 Bla brang ‘Jigs med rgya mtsho, Bla brang bkra shis ‘khyil dang ‘brel ba’i ‘bel gtam chos srid gsal ba’i me long, [Kathmandu], 1996, See p.3 under the “zhu dag pa’i mthong snang”.

8 Alain Fromaget, Lhamo, Choyang: The Voice of Tibetan Religion and Culture, Year of Tibet Edition, Council for Religious and Cultural Affairs, Dharamsala, 1991, pp.321-325 (Editors note)

9 Bod kyi zho ston dus chen, Special Shoton (Opera) Festival 17-21 April, 1993, TIPA, Dharamsala, pp.4-6, 8. (Editors

The opera is one of those central dance of previous feudal Tibetan in and around Lhasa, so it was part of U-Tsang Culture. Opera was not that popular outside Feudal Tibet. Just pointing out the context! It is not ‘the’ dance culture, except common Tibetan language, there is no ‘the’ Tibetan culture or dances because they vary as one travels from places to place. Even Buddhism is not the central or bedrock of Tibetan culture or identity. All these are created in exile, only applies to those who are taught as such in exile about homogeneity of culture and believes, the reality in the Cultural Tibet, the diversity rules and no one try to convince someone else about one’s culture and tradition as “the” Tibetan culture. People are more respective of differences.

NG

An insightful narrative/revelation ~ about the history of Tibetan opera and its struggle for modern revivalism (..against..the milieu of cultural-political correctness).

Thank you Jamyang-la

Sursum Corda ~ Bod Gyalo

Thanks JN la for this wonderful piece just in time around Shoton. It’s great to learn about those subtle but important distinctions between various traditions such as Chungpa, Kyumolonga etc. I want to applaud the selfless efforts all the Tibetans who have done so much to revive this uniquely Tibetan culture which would have been lost had it not been for them.

Culture, Tibetan or otherwise, should not be seen through these simplistic and reductive lenses as some people seem to do and perhaps for some smug selfserving ends. Things don’t have to be in every corner of Tibet to be called Tibetan. It is not Panda express.

Any body who is familiar with Tibetan arts can tell whether something is Tibetan or not wherever in Tibet it comes from.

@NG At least Tibetan feudal society is far greater and better than the one under Chinese occupation. All Tibetans had roof over their head and lived without fear.

Except for few officials no ordinary Tibetan escaped or became refugee enmass under feudal rule before 1950.

According to your logic every country can be reduced to hunter gatherer not just Tibetans but Chinese, Indian, Greek, Romans.

JN la Islam is the least tolerant of all religions. So why you choose Islam to voice your protest of religious right (Buddhist).

@karze: read more! I understand your emotion.

NG

o.k I’m not very familiar with Tibetan opera and never had opportunity to watch any performance. But i’ve watched Drowa Sangmo on Lhasa TV channel.

But I have an affinity for Thangthong Gyalpo ever since my mother introduced Him as Tibet’s first engineer when i was little. He built the Dartsedo bridge and many others.

Excellent article as usual. Great insight into the exile opera untertaking. I have always enjoyed TIPA opera and could watch it for hours, especially as explained by drunken old opera aficionados who never failed to include dirty little anecdotes in their narrative – I would imagine actually meant for the young ladies nearby.

To 1.NG. The Lhamo tradition is not just limited to U-Tsang. Lithang and Drayak in Kham had regular performances of Lhamo. In Bathang the Lhamo performances have even been photographed and written about by American missionaries. I am sure there were other places in Khamo and Amdo where similar traditions were practised, but which we know little about. I should also mention that even in Spiti they practise a kind of Lhamo tradtion called the Bhuchen, which originates from Thangtong Gyalpo. Little knowledge is a dangerous thing NT.

To 2. NT thanks for the kind words.

3. Karze, It was more a joke than a serious protest. I was merely underling the fact that the religious right in the Tibetan community are as intolerant and stupid as the ayatollahs.

@6: Hollywood is tugged in small location in California but represent American culture and entertainment.

Just reading is not enough one need to experience it to fully understand it.

You probably would support the so called glorious 5000 years of Chinese culture and history while tries to rubbishes that is Tibetan.

Jamyang la I know that you meant it as a Joke and agree with your view on Tibetans Religious Right but comparing it to Ayotollah is absurd.

At end of day, JN can assume it must spread in other places as he insinuate. The fact is, he assumes because something has to fit into exile political fanatics who assume Buddhism has all answer to all questions of humans fo political extremist who has the position Tibet was always imdepedependent even fact proves otherwise. When xenophobia reign, there is little room for truth or fact.

Well, i wanna hear your assumption backed up by fact!

NG

I remember watching TIPA’s performance of Sukyi Nyima when I was 10 or 11 in Chakrata. Now I know who that kukpa labu jinpa za khen who made us kids laugh so much was. Long after the performance, some kids would imitate the kukpa and we would all have a big laugh remembering him again. But perhaps the most long lasting effect the performance had – specially on my hormonal balance as a boy approaching adolescence – was the mesmerizing hip movements of Sukyi Nyima.

WELL DONE. !!!

@NG I don’t need to read to know who stole my home. That is plain truth. I have experienced it.

Here we go again.

NG I am assuming you are a fool. If you want fact for this, look in mirror and you’ll see the biggest of them all.

Out of my silence to report that irrelevant, pernicious, and insipid “intellectuals” like young punk are still here arguing over nothing. Nothing important. Young punk spends his/her or transgender life hiding in a closet, afraid to express frustrated feelings of repressed sexuality, projecting his/her frustrations on a failed tibetan independence movement, filled with brother against brother hostility. Young punk, you look in the mirror and you will see that you are NG.

Who is this NG? He sounds like he is at the wrong place.

#18 what is that awfull smell? i thought the rubbish was got rid of! Sigh…

Punk. I think your smelling your burning flesh due to your Shugden worship.

If I have to guess, I say Dolma la pees standing up.

Taking a time to respond to mr JN’s tortuous respond to rebut my point out context, so he can convince his niave exile folks of few kind. First of, in my initial post, I did not rule out complete none existence of “Lhamo” outside political Tibet which was also known as “feudal Tibet”, I mentioned, “Lhamo is not that popular outside this feudal Tibet”, which means it might practiced at few places, possibilities are there, but dramatization of all those stories from Drowa Sangmo to JUnpo Thondup Thonyun are rare. Mr Jn pointed out only three places in Kham, Bathang, Lithang, and Drayap. Then goes onto use his imaginative argument that rest of the places must have it, so NG’s argument of subverting JN’ truthful assertion might be prevented, thus JN hailed as cultural crusader with cultural facts. Lol…….lets do a simple math, the population of UTsang or erstwhile Tibet is less than or equal to 2million and Tibetan population outside TAr or inner Tibet number around as 4 million. Out of 4 million population, how many people are living in those three places? It is insignificant compared to the entire population of inner Tibet. Therefore, JN’s statistics are unreliable at best in terms of representation. Spiti is an Indian territory, so whether they practice your religion or LHamo is none of my concern, you can go there and preach your religion and build schools and bask in self happiness of you are doing something for Tibet as I have been seeing these sort of mentality in the world for sometimes. Exile individuals and institutions milk thenpatronage money of foreign or even Chinese money on the pretext of lessening the suffering of Tibetans inside, in the process their suffering is manipulated and they are the sacred cash cow, then you go and spend the money on Himalayan regional people because we share the same culture. Really? JN”s hasty response does not dwell well with reality. Let me give you an example, when I first came into contact with the exile world, I was constantly faced and bombarded with the so called TIbetan culture and its preservation. Especially, gorshe or circular dance of Ngari or Thoshe. Those were foreign to me as any other cultures. At that time, even slight different regional cultural dance might get in trouble of being different, so being Untibetan, must be either Chinese or diluted by Chinese culture!!!! Linguistic differences faced same kind of discrimination and intolerance due their narrow mindedness and limited knowledge. Thank goodness, with advance of Internet, exiles learned to face of reality of their ignorance. Now they accept Khampa circular dance is totally different from Ngari Gorshe, albeit Khampa dance is more melodious as it was adapted skillfully to modern musical instrument, while Ngari circular dance is only reserved to old people at end of a wedding ceremony. Exile music institution called TIPA faces the same static culture of a specific region than a representation of whole of Tibet. As I said early in the post, there is no such only Tibetan Culture as JN is arguing about. We all have different cultural norms and dances and songs. Only thing we can call only common thread of Tibetan culture and identity is the language called “Tibetan”. Other than that, we are different from each other, even historically if one want to justice to an unbiased history or purported exile propaganda or static unity of Tibet only started from 127 B.C. In the meantime, keep enlightening yourself with real Tibet and try to live with it than distorting it to fit your xenophobic fervor and limited view. Little knowledge indeed is dangerous.

NG

So many Chinese are masquerading as supporter of Middleway and trying to silence the Tibetans who stand for freedom. We see plenty of them here and online – 50 centers.

Despite of not agreeing with Jamyang la with many political stand point, I have lots of respect for Jamyang la. I belive Jamyang La made a tremendous contribution towards developement, reinovation and modernization of TIPA as we know today. Such a contribution is needed and valuable in this volatile exiled Tibetan society. My sincere thanks to Jamyang la. I hope you focus more on contributing in the community rather than activities of exile government and criticise them as if they are our enemy. I am not against your critic but how you do it.

Why my post to repond to mr JN’s hasty and toturous response to my post is still waiting for moderating line while couple of later post is permited to post for public? Oo this is kind of democracy and transparency practiced and envisioned by JN and his web miderator?

NG

26.NG, Sorry for the delay. Thanks for reading this piece and for your comments. JN

Thanks for responsive.

NG

China Calls on the Dalai Lama to ‘Put Aside Illusions’ About Talks

http://www.ndtv.com/world-news/china-calls-on-dalai-lama-to-put-aside-illusions-about-talks-755074?pfrom=home-world

NG

you are clearly a chinese pretend to be tibetans…go to CCP site and express your shit, and chinese supremacism there..no body believe in china superiority outside of china…so don’t waste time to put these shits here

@buddhist outsider: cast aside illusion of wrongly guessing my identity. Intellect should be matched with intellect. Holding deception as truth, in fact is called wrong view in Buddhist cannons. you did not even seem to know this discussion, we disagreed the extent of Lhamo in all Tibetan cultural world. This is not certainly a hegemonic culture!

NG

“China Calls on the Dalai Lama to ‘Put Aside Illusions’ About Talks”

Don’t every CCP white paper or toilet paper say something similar? China belongs to Chinese, and Tibet belongs to Tibetans. And while the filthy rich CCP Princes are able to buy world conscience, China is hallucinating if she thinks Tibetans will ever stop fighting for their native homeland.

NG: Chinese are pathological liar specially the party officials from Mao to Xi.

@Karze: I am not concerned what are Chinese! Go and read crony kudras exposed in Gyalo Thondup’s new book, other kudras making the noise of defense of robbing government gold. Making the round online…..go and feast on it!

NG

alert(“I am an alert box!”);

jamyang lak great…

Dear Jamyang-la,

Very lively reminiscence of Dharamsala TIPA in 1970’s and 80’s. Will go as an important part of our diaspora history. It reflected in some forms history of the struggle between conservatives and modernists during and after the 13th Dalai Lama period in Tibet. I have a feeling that now is the time that some graduate students of modern Tibetan history should take up independent research study on persons of distinct nature like Dawa Norbu, K. Dhondup, Jamyang Norbu, Tashi Tsering, Juchen Thupten, Gyari Lodi etc. juxtaposed with Dharamsala exile history before it is too late.

Thank you Jamyang-la.

Tsepak Rigzin

People of Tibet have the right to define Tibet, people of Tibet know where they belong, people of Tibet know Tibetan culture and history. People of Tibet will determine future of Tibet.

Words coming out of China or anybody else about Tibet and Tibetans have no validity what so ever. This is the message for NG.

A Factual Account of the Tibetan Government’s Gold and Silver

http://www.phayul.com/news/article.aspx?c=4&t=1&id=35978&article=A+Factual+Account+of+the+Tibetan+Government%E2%80%99s+Gold+and+Silver

Dear Mr. Norbu,

My name is Nilanjana Sen and I am the Associate Editor (Culture) at Fair Observer, a news analysis journal giving voice to a plurality of perspectives from around the world. We are an independent media non-profit, with readers in over 200 countries, aimed at addressing issues often circumvented by the mainstream media.

Currently we are working on a series on Extreme Ideologies. While researching for the series I came across your work on the Khampas of Tibet. We are looking at an article that would deal with the ideological underpinnings of the armed resistance waged by the Khampas in the 1950s against the Chinese invasion. It would be an honour to have you as a contributor for this topic. Incase you don’t have the time to write a new article we would be happy to republish an article written by you on the same subject.

For the series we would be interested in an analytical article (1200-2000 words).

I look forward to hearing from you.

Best wishes

Nilanjana Sen | Associate Editor (Culture)

Fair Observer

http://www.fairobserver.com

461 Harbor Blvd ǀ Belmont ǀ California, 94002 ǀ USA

Now it is unfortunate the highly controversial Gyalo Thondup has attempted to defame the family of Tsarong. This family particularly has been highly respected for their contributions to Tibet and acknowledged by numerous well known authors, historians and scholars of Tibet. George Tsarong and some officials of the time had kept the matter of the missing gold confidential as it involved the Dalai Lama’s brother, and hence His Holinesses family.

The truth has finally come out after more than 50 years compelling the Tsarong family to reveal the facts, after Thondup’s outrageous allegations in his recent memoirs. Thondup claims that he did not know of any “safety deposit box and had no key” to the gold. In refutation, Paljor Tsarong has listed in detail countering all of the lies Thondup fabricated in order to wipe himself clean of the embezzlement.

Thondup’s accusations has back fired and now has himself entangled. The Tsarong family has responded to these unfounded allegations seemingly with strong facts. The most important piece will be the document that Tsarong has cited revealing Thondup taking out the gold on numerous occasions, and each time signed by Thondup himself. That “smoking gun” is in the possession of the Tsarong family, will need to be disclosed to vindicate the family of Thondup’s charges.

Finally, Thondup says that he went to His Holiness to confess that he was holding up certain “truths” that needed to be told. He uses the Dalai Lama’s permission as if His Holiness approved of the slander on Tsarong by saying “you have served Tibet all your entire life,” the Dallai Lama replied. ” You must open up.” Did His Holiness actually give the nod? Or did Thondup unawares open up a “can of worms” on himself?

And with this book the Tsarong family can also give their side of the story. Becoz it seems in the early years that was the ‘story’ – the ‘rumour’ going around…..

The book Review written by Jonathan Mirsky of the Spectator is quite something in itself.

In High school we heard so much of Tibetan Govt gold and disappearance etc. mostly during gossip. We may not really know the truth as long time has passed and many actors of the time are long dead.

In High school we heard so much of Tibetan Govt gold and disappearance etc. mostly during gossip.

This is a tip of kudra greediness and unholy rule and system.

I don’t believe father”s crime transferred to sons or daughters. But it is important for those Tibetans who were abused by aristocrats and embezzlement must be exposed. I don’t give a damn if you did something for the so called Tibet and meanwhile stealing and abusing public trust. It simply cannot be a reason to justify your theft of great magnitude.

NG

Many of our country folks on private estates were hired as stewards or ‘chanzos’ by the gentry. Truth be told these very ‘chanzos’ that abused our people were our own country folks. The gentry lord was never around in the manor, and these ruthless and merciless chanzoes betrayed the resident citizens in the name of the lordship.

“Government Gold” How could any government or a king for that matter, accumulate such wealth without the people contributing substantially to it? Anyway, I like to believe most of it was spend in good faith-its half a century after the fact, whats the point now? Seems only few people were privy to the facts anyway; the rest, the majority, we have no clue though that wouldn’t stop any of us from believing this story or that story. Plus, China is plundering what they greedily refer to as the Western Treasure House, that much gold and silver, and even pricier precious minerals out of Tibet every hour. They have stolen everything there is to steal, even the sweat off the Tibetan’s back. The real thief is China!!

Tashi Delek Genla! I heard that you have written some plays in english while you were directing TIPA. So I was wondering where I can get hold of them.