Resolving the Mystery of Herodotus’ Gold-Digging Ants

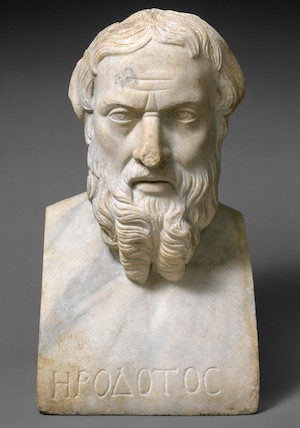

“Father of History”

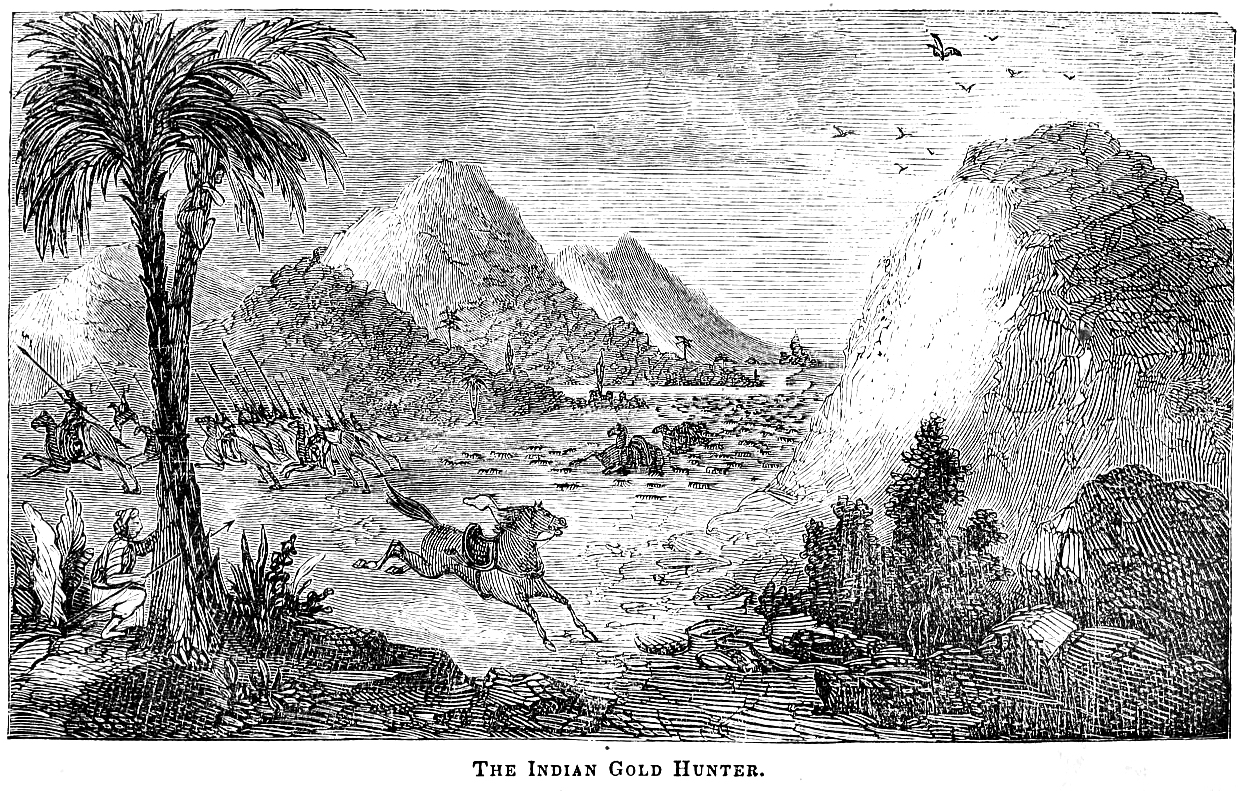

In the world’s oldest history book, if one may call it that, China does not receive mention, neither does Britain, but “Tibet did not escape the notice of the Father of History,” or so Charles Bell tells us. “Writing some two thousand four hundred years ago, Herodotus recounts a rumor about a race of enormous ants that delved for gold in a country to the northwest of India. From time to time, travelers attempted to steal the gold and ride away with it, but the ants gave chase and killed them if they were caught.

One explanation, which has found credence with some scholars, comes from the gold diggings at Thok Jalung in western Tibet. The intense cold of this lofty tableland, aggravated by the violent winds that sweep unceasingly over it, compelled Tibetan workmen to dig hunched up in their black yak-hair blankets. They were accompanied by their watchdogs—usually black, ferocious, and swift—which would certainly pursue and attack robbers in the manner described by Herodotus.” [1]

Other early travelers, such as Charles Sherring, arrived at the same conclusion: “This belief that Tibet was an Asiatic El Dorado can be traced back in Europe to Herodotus, ‘the father of history,’ and the first writer in the West to refer to this shadowy land north of India.”[2]

The Marmot Theory

Contemporary historians Tom Holland, William Dalrymple and others have, more recently, embraced an alternate theory laid out by French explorer Michel Peissel in his book L’or des fourmis: La découverte de l’Eldorado grec au Tibet.[3]

Peissel reported that in an isolated region of northern Pakistan on the Dansar Plateau in Gilgit-Baltistan province, there is a species of marmot—the Himalayan marmot—that may have been what Herodotus called giant ants. According to Peissel, he interviewed the Minaro tribal people who live in the Dansar Plain of “Little Tibet,” and they confirmed that they have, for generations, been collecting gold dust that the marmots bring to the surface when digging their underground burrows.

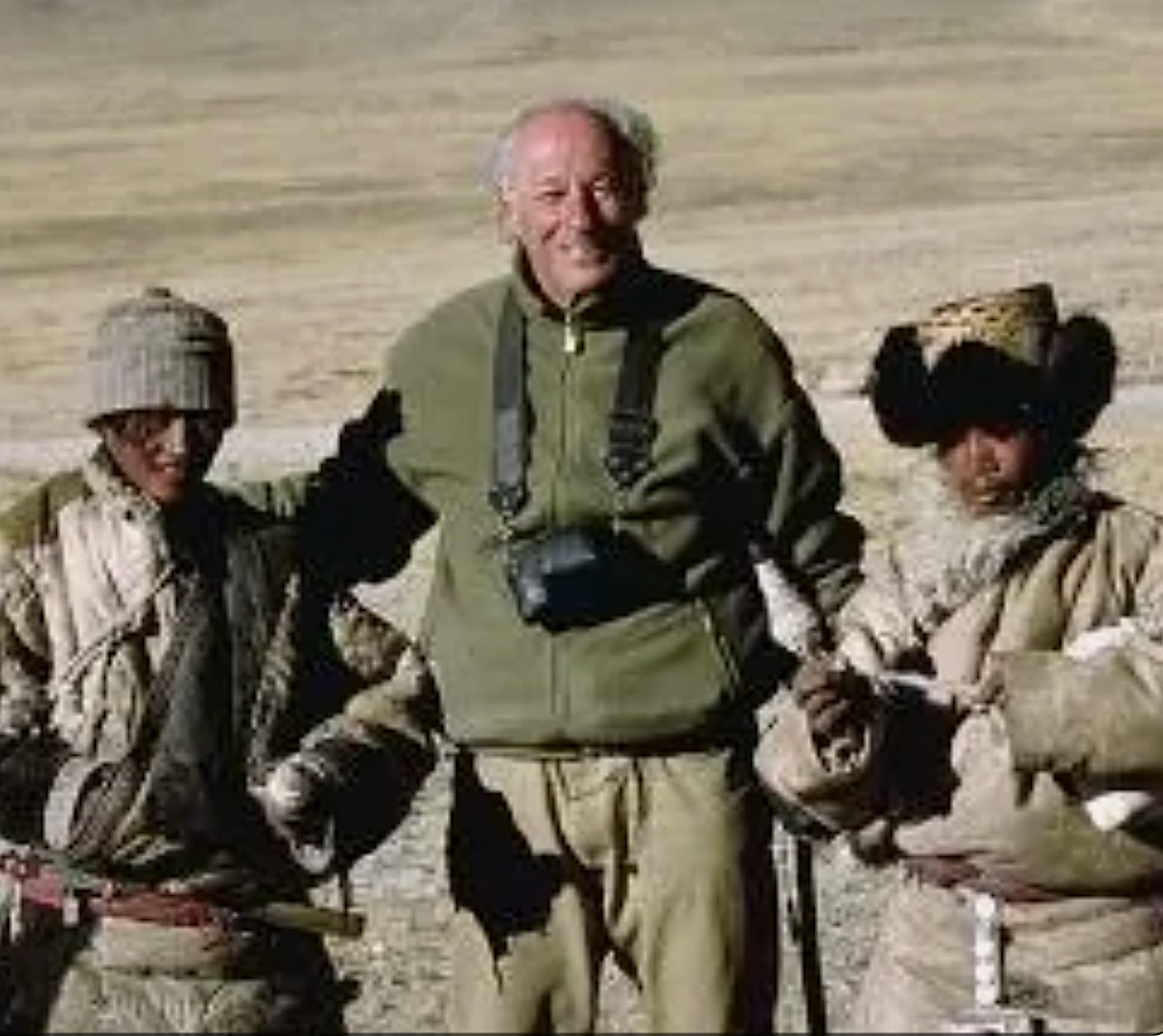

In an article in Time Magazine, Peissel claimed that he had disguised himself in garb like that of his two local guides, staining his face with walnut dye in order to enter a region long forbidden to foreigners.[4] Unfortunately, according to M. Ashraf (former Director General of Tourism, Jammu & Kashmir), Peissel never went to the Minaro area. He stayed the entire time in Kargil Tourist Bungalow, where he interviewed some members of the Drokhpa (Minaro) tribe. Ashraf claimed to have known Peissel and met him in Paris and later at Zanskar.[5]

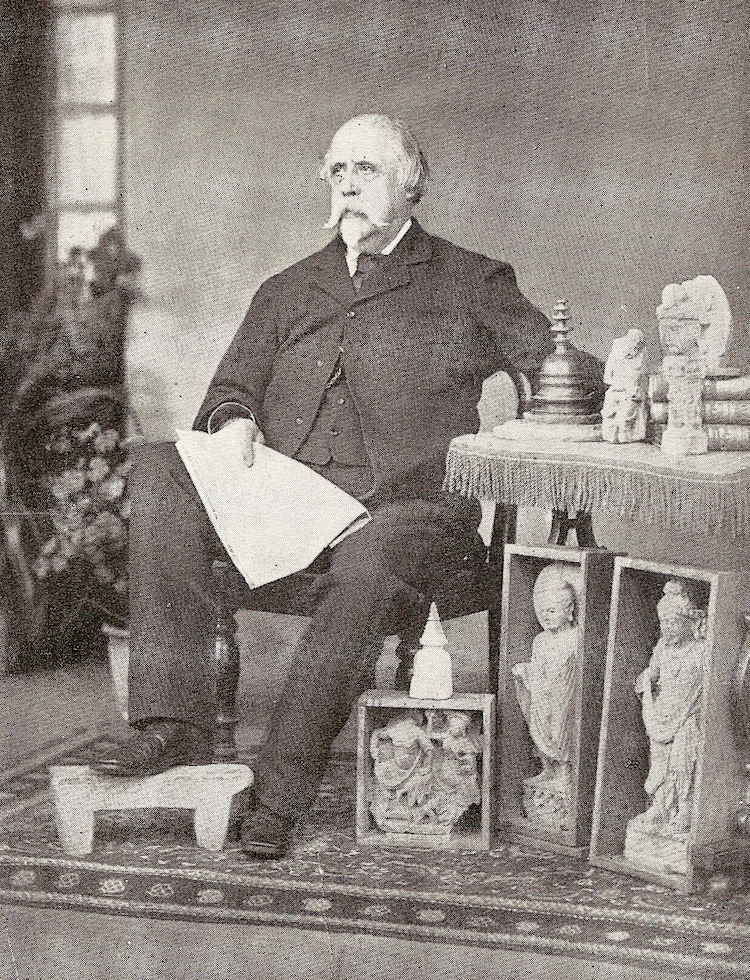

Alexander Cunningham, founder of the Archaeological Survey of India and its first Director-General, was in this area in 1847 and wrote that “… on the plains along the banks of the Indus and Shayok, the marmots throw up the earth mixed with gold-dust, from which the Indians of Balti occasionally extract a few grains of gold.”[6]

Why the Marmot Theory Falls Short

The phenomenon of marmots throwing up “a few grains of gold” when digging their burrows is no doubt remarkable, and perhaps charming in a YouTube animal video sort of way. But though the marmots might have made a small contribution to the local Balti economy, these “few grains of gold” could not possibly have attracted the attention of the fabulous Persian Empire, from where Herodotus got his story.

The crucial point in Cunningham’s account is that the “few grains of gold” are dug up by the marmots on the banks of the Indus and its Shayok tributary. This means that the gold must have originated from somewhere further upstream, where the “motherlode” would have been. That would be the source of the Indus: the vast Jhangtang plains area around Mount Kailash, where the Thok Jalung goldfields happen to be located.

Thok Jalung & Other Goldfields

The author Peter Hopkirk writes that the East India Company’s appetite for Tibetan gold had first been whetted when, in 1775, the Panchen Lama sent Warren Hastings some gold ingots and gold dust.[7] This fascination received fresh impetus when the Survey of India’s spy-surveyor, Pundit Nain Singh Rawat, returned from Tibet. Among the intelligence he brought back were reports of rich goldfields in the western parts of the country.

Nain Singh was the first non-Tibetan to visit Thok Jalung — on August 26, 1867. Thok Jalung was a highly productive gold-mining area, and Nain Singh reported seeing one nugget weighing nearly two pounds.[8] The goldfield was about one mile long, with a small stream running through it, used to wash the gold out of the soil. Miners lived in yak-hair tents pitched in holes two or more meters below the ground. There were about 300 miners during the summer and over 6,000 during winter, as frozen ground was less likely to collapse. Since miners’ families often stayed onsite, one author has suggested a winter population of 20,000 at Thok Jalung—all gathered for the purpose of mining gold.

What should be mentioned is that nearly every family or tent at Thok Jalung would have had at least one guard dog, a Tibetan mastiff, which were big, savage, and usually black in color. Heinrich Harrer does not fail to mention that he and Aufschnaiter were constantly fighting off “exceptionally aggressive and ferocious” dogs during their travels across the Jhangtang.[9]

Peissel theorized that Herodotus may have confused the old Persian word for “marmot” with the word for “mountain ant.” But I don’t think there were any “mountain ants” in Persia capable of “chasing and devouring full-grown camels,” as Herodotus in a follow-up passage, claims his giant “ants” were able to do.[10] A pack of savage Tibetan mastiffs, however, were more than capable of such feats.

Sven Hedin, who traveled through the area, wrote: “The Tok-jalung goldfield, at a height of 16,340 feet, is one of the highest permanently inhabited places in the world.”[11]

Charles Sherring, traveling through this area before 1906, wrote of one of the tributary streams of the Indus passing “through miles and miles of rich gold fields, of which, perhaps, Thok Jalung is the best known.”[12] There, besides the gold miners, he encountered two Tibetan officials, one of whom was the Sarpon. “The word ‘sar’ means ‘gold,’ and this officer bears this name inasmuch… he collects the taxes from the gold-diggers. The tax is from ten to twelve rupees per head annually and is a poll-tax on every digger. Considering the output, the tax is merely nominal.”

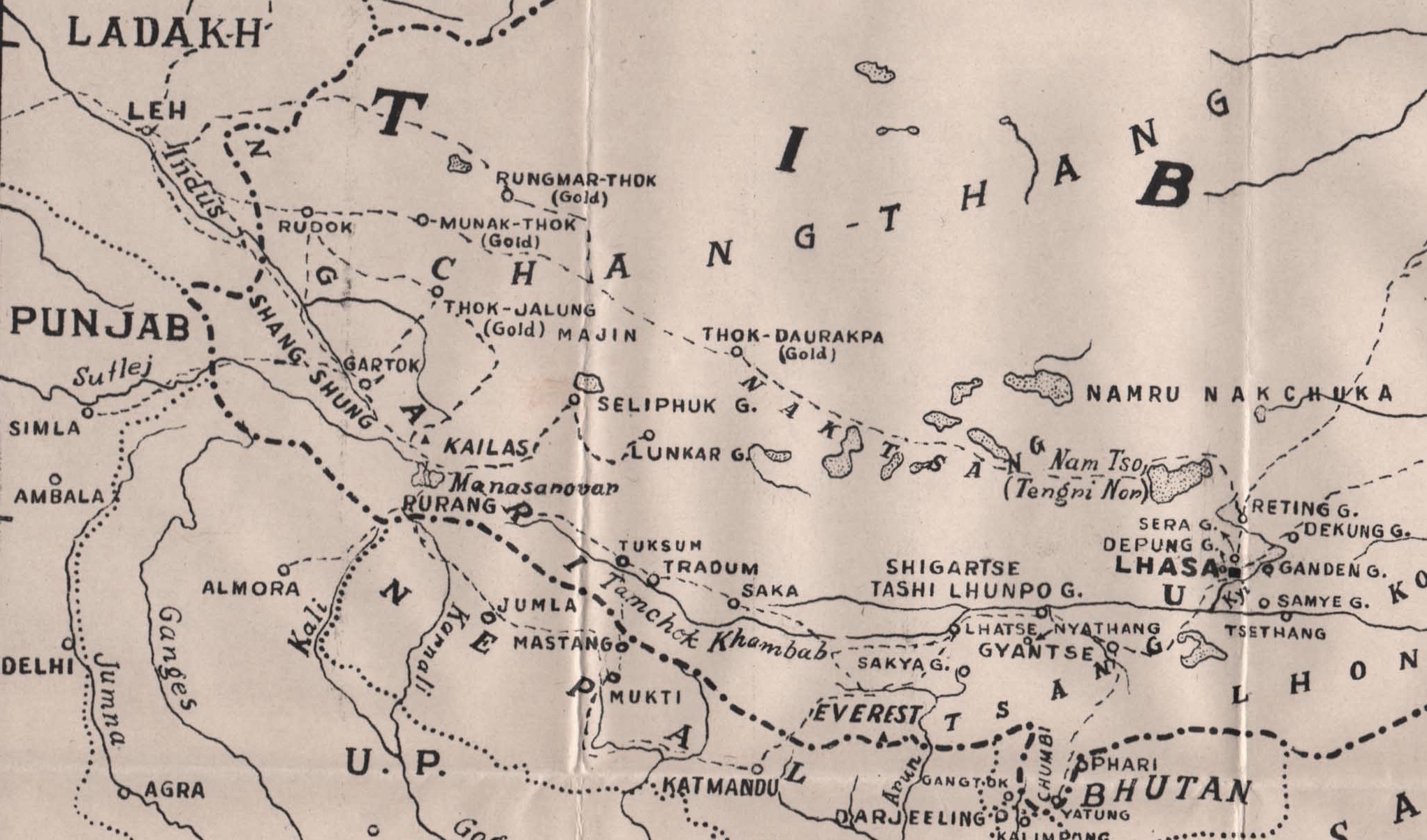

Besides Thok Jalung, there were other goldfields in the region, including Thok Daurakpa, Munak Thok, and Rungmar Thok, all immediately north of Kailash. “Thok” is a synonym for “ser” the more common Tibetan word for gold. According to Derek Waller, “thok” is Tibetan for “gold” or “goldfield,” while “Jalung” was the name of the area.[13]

I have reproduced an old Survey of India map where the names of all these goldfields have been clearly noted with the additional information “gold” in parentheses below the names.

Conclusion

The Tibetan Empire had not been established when Herodotus wrote his history, but the kingdom (or civilization) of Zhangzhung then covered the whole of what is today western Tibet, Ladakh, and Gilgit-Baltistan. Some PRC-influenced archaeological and historical sources claim that Zhangzhung was established between 1500 BC and 1 AD, but a more conservative timeline is 500 BC to 625 AD. Either way, a definite connection with ancient Persia can be postulated. Some scholars have floated the theory that the Bon religion of Zhangzhung was influenced by or derived from Persian systems like Zoroastrianism or Mithraism.

One of the mysteries that this study cleared for me was where the Tibetan Empire might have acquired the resources it surely needed to create the great military machine on which it was founded. Was Songtsen Gampo’s campaign against Zhangzhung motivated by the goldfields of western Tibet?

Another reason for this study was to reemphasize the tremendous antiquity of Tibet (and its shadowy predecessor Zhangzhung) stretching back to early world history. This matters, particularly at a time when the very name “Tibet” is being alarmingly “disappeared” by Communist China, and even some academics and suchlike in the West are nervously looking for ways to avoid mentioning that name, even in works about, or related to, that ancient nation.

Endnotes

[1]: Charles Bell, The People of Tibet (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1928).

[2]: Charles Sherring, Western Tibet and the British Borderland (London: Edward Arnold, 1906).

[3]: Michel Peissel, L’or des fourmis: La découverte de l’Eldorado grec au Tibet (Paris: Robert Laffont, 1984).

[4]: Michel Peissel, “The Ants’ Gold: The Discovery of the Greek El Dorado in the Himalayas,” Time Magazine, November 1984.

[5]: M. Ashraf, personal communication and published correspondence regarding Peissel’s visit to Kargil.

[6]: Alexander Cunningham, Ladak: Physical, Statistical, and Historical (London: W.H. Allen, 1854).

[7]: Peter Hopkirk, Trespassers on the Roof of the World: The Secret Exploration of Tibet (Los Angeles: J.P. Tarcher, 1982).

[8]: Nain Singh Rawat, field reports submitted to the Survey of India, 1867.

[9]: Heinrich Harrer, Seven Years in Tibet (London: Rupert Hart-Davis, 1953).

[10]: Herodotus, The Histories, Book 3, passage 105.

[11]: Sven Hedin, Trans-Himalaya: Discoveries and Adventures in Tibet, 3 vols. (London: Macmillan, 1909-1913).

[12]: Charles Sherring, Western Tibet and the British Borderland (London: Edward Arnold, 1906).

[13]: Derek Waller, The Pundits: British Exploration of Tibet and Central Asia (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1990).