Bill Gates and his impressive spouse, Melinda, have accomplished an enormous amount of good works throughout the world, not least being the eradication of polio throughout India. But one project of the Gates Foundation, the creation of an affordable “practical” toilet suitable for a single-family residence in the developing world, has always come up against a fundamental hitch.

Last month Bill was at Beijing for the “Reinvented Toilet Expo” event where he reviewed the twenty cutting-edge sanitation products that were on display. They were very impressive. One could convert poop into energy for cooking, the other transformed sewage sludge into potable water (Bill drank a glass). But exciting and high tech as they all were “… the economics of such a solution remain uncertain” as the Gates Foundation admitted some years ago. In plain English: No one can afford them.

Tibet’s Low Tech “Secret”

This got me thinking about my own experience with Tibetan style toilets and how unexpectedly impressed I was by its low-tech ingenuity when I first used it in Mustang, at our HQ building at Kalsang Phug. It was just a small room on the second floor with a hole in the floor –– a gap between the floorboards. But the surprising thing was the relative absence of the foul stench that is the norm with toilets in the sub-continent and China. I first credited that to the cold and altitude of the place, but later learned that the crucial deodorizing factor was the pile of wood-ash on one side of the hole. You took a shovelful of this ash and spread it down the hole after you had done your business.

Some years later I mentioned my observations to my uncle the scholar Sonam Tomjor (Tethong) in Dharamshala. He immediately launched into a long discourse on the merits of the Tibetan toilet or “depository of secrets” (tib. gsang bchol) as has been translated by Charles Bell, if I remember correctly. Tomjor-la had been a great friend of Gedun Chophel in Lhasa and shared the intellectual interests and humanist viewpoint of our great scholar/poet –– and some of his eccentricities as well.

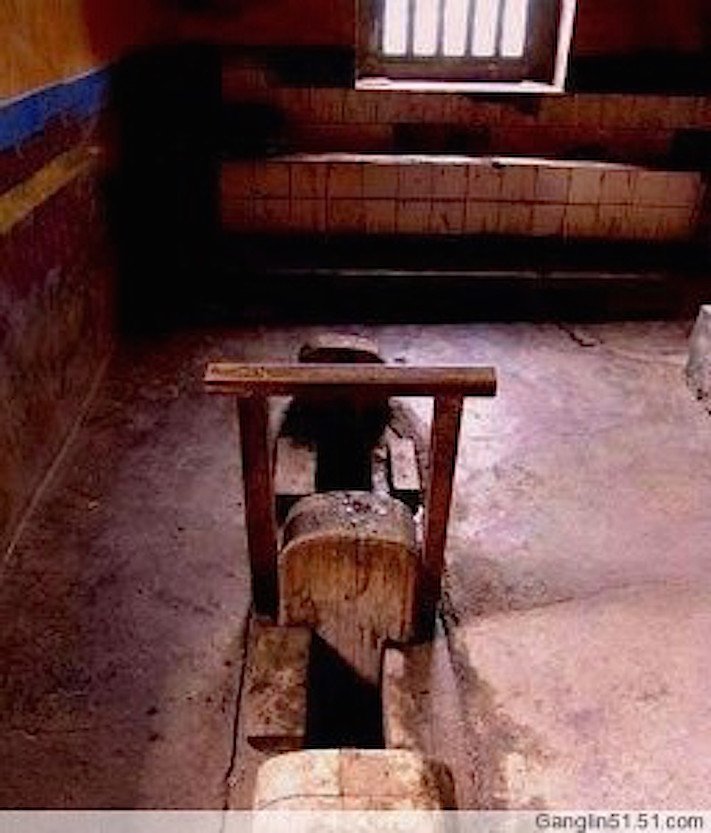

The toilet in most traditional Tibetan homes were on the second floor (or higher) and always at the back of the house, which would be north-facing and the coldest side of the house. The room immediately below the toilet, which was closed off from the rest of the house, had a small door or hatch on the outside. So you did your business through the hole in the floor and the waste dropped directly into the collection room below –– with no intervening pipes or any mechanism. So you never had to call a plumber. Every evening, ash from the household kitchen fire was collected in buckets and deposited in an open bin in the toilet, which had a small wooden spade stuck in it. You used the spade to pick up the ash and spread it through the hole after you finished. My uncle Tomjor-la maintained that the “secret” of the Tibetan toilet was essentially the ash from the household kitchen fire.

In many places around the world kitchen ash was (and probably still is in the developing world) used as a cleaning agent. It is mixed with water to form a paste and used in washing crockery, pots and pans etc. Ash paste is often used for polishing brass and silver and is as effective as any commercial product.

For Hindus cow-dung ash is not only sacred but a purifier, and has medicinal properties. It is the essential ingredient in the making of vibhuti or sacred ash which is used for tikas and applied all over the body of sadhus.

The fact of kitchen ash being a natural deodorant, even a disinfectant, is well known. Wood ash is such a marvelous deodorizing compound that in the backwoods of Tennessee (where I’ve lived for the past seventeen years) when your dog has run into a skunk and been sprayed, the only effective way of removing the otherwise powerful and long lasting odor, is not by washing him with water and soap or anything else, but rubbing him vigorously with ash all over his body.

The Potala Toilets

The layer of ash between the waste matter certainly kept the toilet smells to a minimum even if it did not eliminate them all together. Another fact that helped was that the toilet room itself was some distance higher (at least ten of fifteen feet) from the room below where the waste matter was collected.

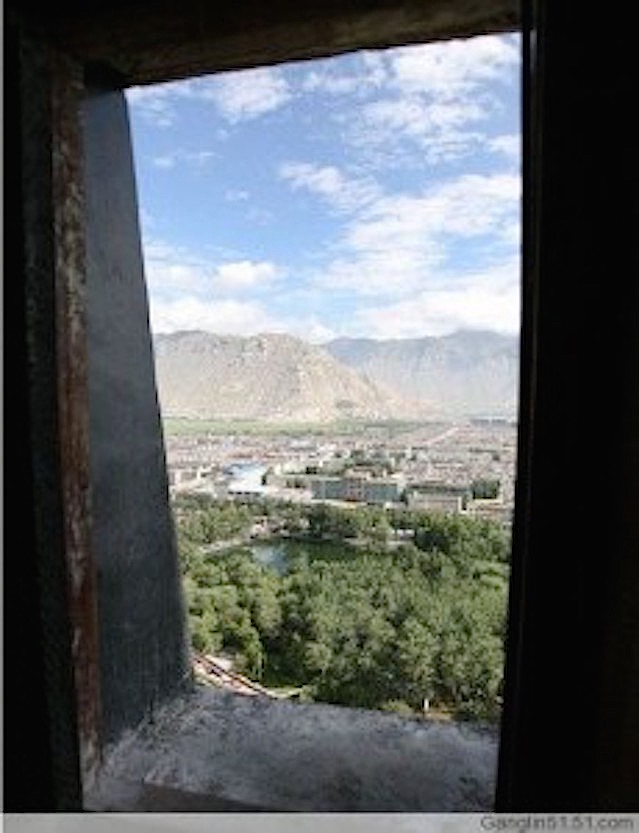

All Tibetan have heard of the toilets at the Potala Palace which are so high up that it takes quite a while for you to hear your “whatever” hit the bottom. A Tibetan blogger “Kangling” (thigh-bone trumpet) has written on the curiosity displayed by Chinese tourists at “ … the Potala Palace’s Changsur (north-corner) Toilet, ‘the highest toilet in the world’. Some Chinese have sarcastically advised that ‘people with high blood pressure and heart disease shouldn’t use this toilet’.”

Recycling “Par Excellence“

Once a year, probably around the end of autumn, farmers would come to Lhasa with strings of donkeys to clean out the toilets. The door or hatch at the back of the toilet would be opened and the waste matter shoveled out. My uncle Tomjor-la insisted that it didn’t smell that much because it was mixed in with the ash, but probably it had also dried out considerably because of the general dryness of the Tibetan air. The waste-matter would be bagged into coarse yak-hair sacks and loaded on the backs of the donkeys. The farmer would then wash his shovel and drive his donkeys back to his farm where he would spread the fertilizer over his fields, where it would decompose and mix in with the soil, till spring plowing. From what I was told it seemed that when farmers emptied toilets in rural areas they would pay the house-holders some small amount, a trangka or two, such being the value of this human fertilizer. But in towns and cities like Lhasa or Gyangtse they did not pay.

Christoph von Fürer-Haimendorf, the Austrian ethnologist, who published his masterly study on the Sherpas in 1964, observed that the Sherpas of Solokhumbu paid Tibetans who had come across the border (who they called “Khampas”) to clear out their toilets for them annually. Haimendorf mentions that the rather stiff price of Rs. 30 per toilet was charged by the Tibetans. This is just conjecture but it is possible that the Sherpas may have become influenced by Nepali/Hindu caste prejudices, where any task involving handling of human waste was an big taboo. No such prejudices (tib. namtok) existed in Tibet.

Tibetans are, of course, no more hygienically inclined than other people. Some might even say they were less so. So why did most homes in Tibetan villages and even in Lhasa have basic toilets from the old days, when the lack of toilets in the rest of the developing world (including China) is still an enormous problem that the Gates Foundation with all its resources is unable to overcome? From India we have had a succession of news report about “lack of toilets increasing rape attacks on women”. So much so that Bollywood has released a film with a social message Toilet: a Love Story, highlighting this issue.

This is just a throwaway speculation of mine but I think that in the case of Tibet, it was recognized from very early on that human waste was not an icky pollutant but a valuable resource, one that had to be collected and stored –– hence toilets. Most of Tibet is arid, especially Western and parts of Central Tibet. Agricultural land is generally of poor quality and such naturally occuring mulch or composting agents as leaves, grass etc., are not plentiful. Furthermore even animal dung cannot be spared for fertilizing fields as it is required for cooking and heating fuel. So in the end all you have is yak-dung ash and human waste to grow your crops. So naturally you had to have a store-room (or toilet) at the back of your house to husband this precious resource .

The use of human excrement as fertilizer was common practice in ancient times in Europe and Asia. These days this is still widespread in China and in some developing nations. The use of untreated human feces as fertilizer is a risky practice as it may contain disease-causing pathogens. These risks are eliminated by proper composting but this this does not happen in China, from accounts I received from prisoners who performed forced labor in Laogai prison farms. Raw human feces is mixed with urine and stirred by prisoners in large slurry tanks or ponds. The “precious” liquid mixture is carried out on the fields in pairs of “honey buckets” or old kerosene cans hanging from bamboo poles. This foul-smelling slurry is then ladled out carefully by prisoners on individual plant shoots. All Tibetans who did laogai slave-labor (nyetsoe) will know what I am talking about. Otherwise check out the great Laogai classic, Prisoner of Mao. It is out of print, but you can buy second-hand copies for a dollar or two.

But the Tibetan method of letting the human waste-matter and kitchen-fire ash pre-mix in the toilet itself, started the process of decomposition and the elimination of harmful pathogens. This process was completed when the waste was spread out over the land and allowed to mix into the soil throughout the winter by which time the composting process would be complete and disease-carrying bacteria would be eliminated. Wood ash by itself has been used in agricultural soil applications, even in domestic gardening in the West, as it recycles nutrients back into the land.

Animal dung (yak, cow, horse, etc.,) was the principal source of fuel in most of Tibet. Wood was a scarcer resource except for parts of Kham and southern Tibet. In Lhasa peat (tib. laama) dug up from around the Kyangthangnaka suburb was sometimes used. Not only was animal dung a completely renewable source of cooking and heating fuel in Tibet, but the full recycling of the resulting ash to aid in the composting (and sanitizing) of human waste for fertilizing the soil, advanced this process a crucial step further. I would go so far as to call this the most comprehensive and self-sustaining recycling system in the world.

Sanitation in old Lhasa City

Most toilets in Tibetan village houses were probably fairly clean. I came across a traditional toilet in a farmhouse at the village of Phey in Ladakh that I can only describe as pristine. But Lhasa did have sanitation problems, almost certainly as it as it attracted a large number of pilgrims from all over Tibet and other parts of “High Asia”.

But early British accounts of “… the appalling filthiness of the Holy City” have always been suspect to me. Their intentions are, more often than not, to represent Tibet as a backward feudal society in thrall to superstition and villainous priests. The British demonized Tibetan society and government (before we signed the Treaty of Lhasa in 1904) for the same reason the Communist Chinese did –– to justify their military invasion, period. But I repeat, Lhasa did have a sanitation problem.

Though the permanent population was not large, an endless flow of pilgrims definitely contributed to the problem of keeping the city clean. There does seem to have been public toilets of one kind or the other in Lhasa –– but probably not enough of them. Heinrich Harrer mentions that a public toilet collapsed during the great 1950 earthquake and Shakabpa writes that the 13th Dalai Lama, after his return from India, ordered public toilets to be built. Although private houses had their own toilets, I am fairly certain that the few public toilets and the shared toilets of common courtyards had problems in maintaining an acceptable level of cleanliness. Rebecca French in The Golden Yoke: The Legal Cosmology of Buddhist Tibet cites “the case of the smelly toilet” that the Lhasa municipal court had to deal with.

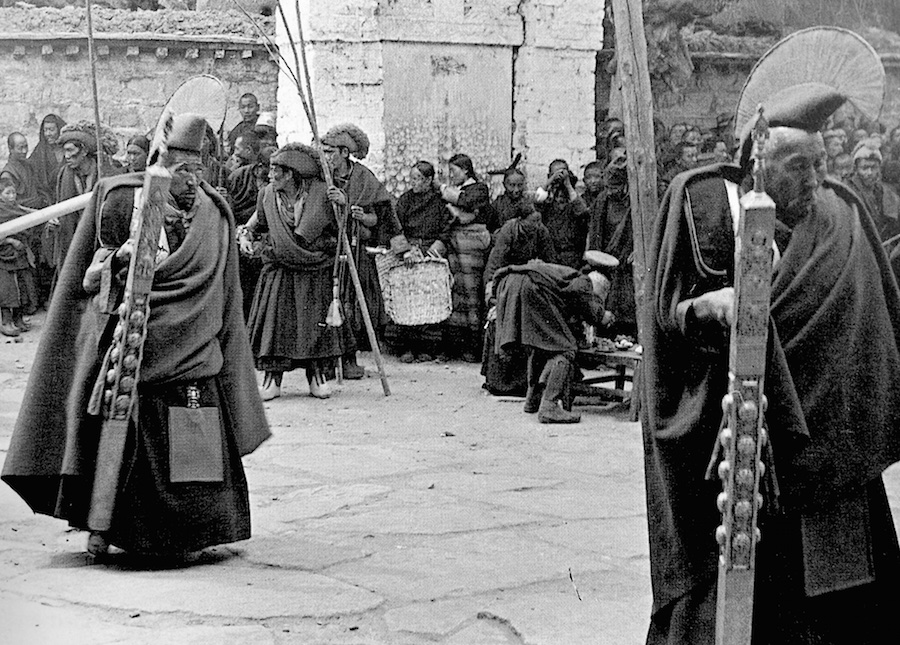

But for a couple of month or so every year, around the period of the New Year and Monlam Festival, Lhasa city became spotlessly clean.The legal authority of the city was handed over to the monk disciplinarian of Drepung, the Tsokchen Shalngo, who with his dob-dob enforcers regularly inspected every neighborhood and street of Lhasa and made sure they were spotlessly clean. Otherwise the householders in that vicinity would have to pay heavy fines or even be beaten if they did not do so.

There is a story of a Lhasa householder who had cleaned up the street in front of his house and was waiting for an inspection by the Shalngo and his staff. Just when the inspectors were coming around the corner a stray dog trotted by the front of the Lhasawa’s door and dropped a large poop. The frantic householder looked around and realized there was no time to clean up the mess, and that the inspectors would be on him in a minute. He quickly took of his hat and dropped it over the dog-poop, and bowing respectfully waited for the Shalngo and his dob-dobs to move on. He got away with it.

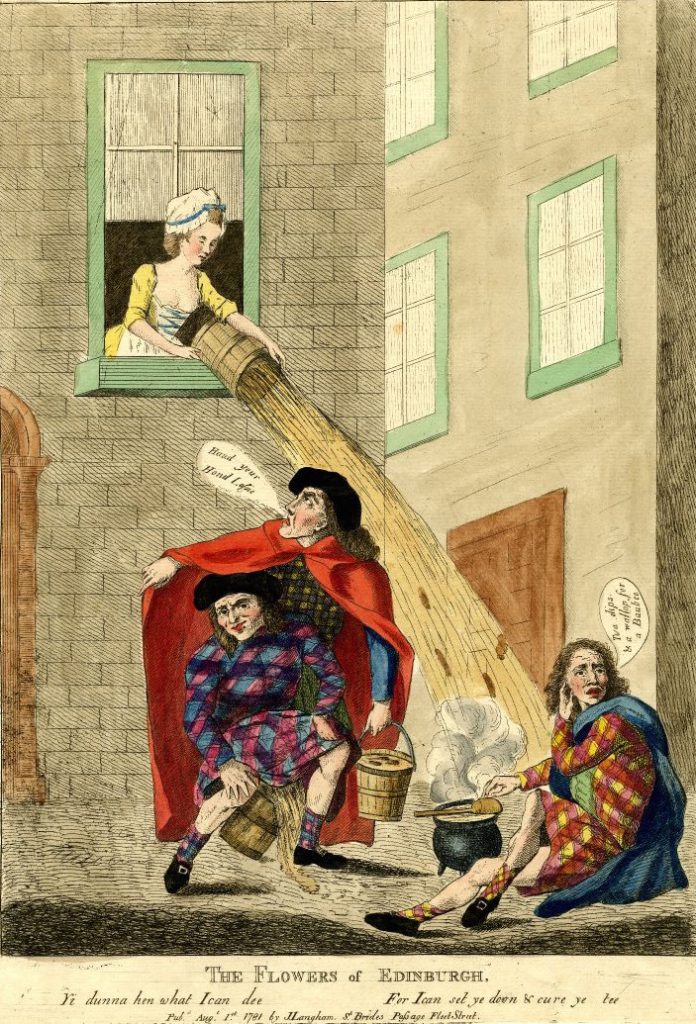

I don’t know how the situation is these days but when I was in Kathmandu in the early seventies, the sanitary situation in the old city was really dreadful. The tourist part of town had flush toilets but the residents of the old city dropped feces and urine out of the windows of their old houses, especially in the mornings. But in Kathmandu’s defense I should say that this was fairly common practice in European cities, in medieval times.

When I lived in Edinburgh in Scotland I was told that in days of yore pedestrians would have to dash from door to door, dodging chamber-pots and buckets of urine and faeces tossed from above. Tenants would yell “gardy-loo”, a corruption of the French gardez l’eau, ‘watch out for the water!’ In Kathmandu no warnings were given.

On a guided tour of the Tower of London I noticed that the ancient structure had only one toilet. The great Chateau de Versailles (that I visited in 1972) definitely didn’t have a single toilet. Chamber pots (tib. chapto) were en vogue then I was told. By comparison, Dzasa J. Taring’s in his Index and Plan of the Lhasa Tsuglakhang (1980) lets us know that Tibet’s sacred Temple complex had at least four toilets (tib hon. zemchoe) – one was for the Dalai Lama’s apartment.

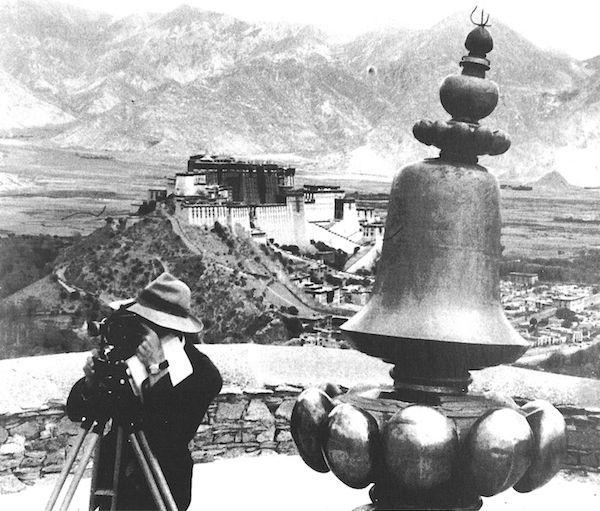

It appears that in the mid forties the Lhasa Municial Office (tib. lhasa nyertsang) on instructions from the Kashag initiated a project to improve sanitary conditions in Lhasa. Harrer tells us that “They wanted us to build a sewer system. In order to do this work, we had to have an accurate map –– all that existed so far were very rough drawings.” Using a theodolilite borrowed from Tsarong, Peter Aufschnaiter, assisted by Harrer, surveyed the city and produced the first modern map of Lhasa. A whole slew of other projects were planned, including a new hydro-power plant, a steel trestle bridge across the Kyichu, etc. A team of “experts” came together including our two Austrians, radio-man Robert Ford, the White Russian mechanic, Nedbailoff, and such Tibetan officials as Tsarong (father and son), Ringang, Thangme, Jigme Taring and others. But then, of course, the Chinese invasion put a stop to all that ––and so much more.

The sanitation situation in Lhasa these days has probably not improved. I heard on the grapevine that the enormous increase in Chinese tourism and the frenetic construction of shopping plazas and mega-hotels (with flush toilets) have definitely destroyed the Lhasa ground water, and further contributed to the drying up of the Kyichu River.

But to conclude on a lighter note here is a 2015 post from Tsering Woeser-la, “Lhasa’s Important Toilets” (translated by High Peaks Pure Earth). It will certainly amuse, but more significantly may enlighten us on the ideological ramifications of toilets and VIP visitors to the Holy City.