Late one night in October 1988 I was woken by a telephone call from the United States. I was living in Japan then, teaching English and writing the occasional book review for the Japan Times. My twenty year work stint in exile Tibetan society had ended a few years earlier when I had been dismissed (with the aid of a violent McLeod Ganj mob) from my post as director of the Tibetan Institute of Performing Arts (TIPA) for the alleged irreverence of a couple of my plays.

Late one night in October 1988 I was woken by a telephone call from the United States. I was living in Japan then, teaching English and writing the occasional book review for the Japan Times. My twenty year work stint in exile Tibetan society had ended a few years earlier when I had been dismissed (with the aid of a violent McLeod Ganj mob) from my post as director of the Tibetan Institute of Performing Arts (TIPA) for the alleged irreverence of a couple of my plays.

An urgent voice in Tibetan asked “Jamyang Norbu, Jamyang Norbu, can you hear me. I am Thupten Jigme Norbu.” For a while I couldn’t place the name and then realized it was Taktser Rimpoche, the Dalai Lama’s oldest brother.

“Yes Rimpoche I can hear you, how are you?”

“Jamyang Norbu, Jamyang Norbu, do you know what has happened.”

“What is it Rimpoche?”

“They have given up our rangzen.”

“Rimpoche, what are you saying?

“Gyalwa Rimpoche made a statement at this place, Strasburg…”

And he told me what had happened.

I am not on terms of any real intimacy with members of the Dalai Lama’s family, and it took me a little while to figure out why Taktser Rimpoche had contacted me. It probably had to do with my writings in the Tibetan Review, where I had been regularly analyzing and condemning the Tibetan government’s policy of downgrading Tibetan independence to conciliate Communist China. My last contribution had been a two-part article (“On the Brink”, Oct-Nov1986) warning of the increasing Chinese population transfer into Tibet. I stressed that the only way to deal with this crisis was not to appease Beijing but to actively discourage business, tourism and investment in Tibet. Destabilize the region. In those early years of Deng’s liberalization there was an opportunity to do something like that. Officialdom, of course, ignored my report. A couple of inji readers accused me of sabotaging the wonderful new relationship between the Chinese and the Tibetans.

“And what are you going to do?” Rimpoche asked me at the end of the conversation.

What could I say? I told him I didn’t know; that I wasn’t in any position to do anything.

I think I disappointed him with my answer, but that conversation started a friendship, nonetheless. There was, on both sides, a bit of emotional dependence in this relationship. Those who espoused the cause of independence became increasingly marginalized in exile society and accusations of “opposing” the Dalai Lama were readily hurled at those who expressed any doubt at the Middle Way approach. So even if you happened to live at the opposite ends of the earth, you took strength in the friendship, no matter how long distance, of those few Tibetan who would not give up rangzen.

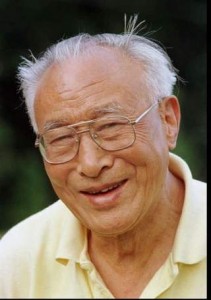

Rimpoche wasn’t a spring chicken then, in fact he was 73 when with the help of Lawrence Gerstein he founded the International Tibet Independence Movement and led a number of independence walks that took him all over the United States and Canada. I was back in Dharamshala during those years, editing the Tibetan newspaper Mangtso. It was always an uplifting experience to see a photograph of Rimpoche on one of his marches, striding vigorously, his white baseball cap tilted back on his head, telling America that Tibet was an independent country and that Americans had to support the cause.

He always seemed to make his statements with a big smile. Rimpoche wasn’t one of your grim, teeth-gritting nationalists. His conviction regarding rangzen did not come from any hatred of the Chinese people or some ultra-patriotic doctrine or philosophy, but merely that he had no illusions about China’s real intentions regarding Tibet. Rimpoche was convinced that Tibet needed independence not for some exalted ideological reason but as a fundamental condition, an essential requisite for the survival of the people, their language, their culture and even their religion. Rimpoche was certain there was no other way.

I feel Rimpoche had this clarity in his thinking because the Communist leaders he first encountered in Amdo, when he was abbot of Kumbum monastery, were the real deal: crude, self-righteous, devious and murderous men — de-humanized progenies of the unbelievably savage Chinese Civil War. Rimpoche describes them very accurately in his autobiography Tibet is My Country. Left wing propaganda a la Edgar Snow has left us the impression of Chinese Communist cadres and officers as idealistic agrarian reformers with a soupçon of the Taoist sage about them, but anyone who has some idea of the history of the Chinese Communist party will be aware how many in the Red Army were ex-warlord officers, mercenaries, former bandits, ex-junkies and the like. Rimpoche also witnessed how the Communists dealt with opposition when they wiped out the Muslim Huis of Lusar, close to Kumbum. Rimpoche was also in Amdo when the Red Army slaughtered the Amdowas of Nangra and Hormukha and started their genocidal campaign against the Goloks.

In Amdo the Communists do not appear to have tried to win over people with guile and sweet-talk. Most probably they felt that Qinghai was theirs anyway, and they didn’t have to bother. The outcome of their invasion of Tibet, on the other hand, was far from certain, and the Communists were careful that their representatives in Lhasa and Chamdo were outwardly pleasant, smooth-tongued people.

The first Communist officials that His Holiness the Dalai Lama met and interacted with in Tibet were attractive and charming equivocators like Baba Phuntsog Wangyal and Liu Ke Ping the ideologue, both of whom taught the Dalai Lama Marxism-Leninism, the history of the Communist Party and the Soviet Union’s nationality polices. Phuntsok Wangyal mentions in his autobiography that “The Dalai Lama was very eager to learn about all aspects of communism, and I think we had an effect on his thinking. Even now, he sometimes says that he is half Buddhist and half Marxist.” We should bear in mind that His Holiness was very young, in his formative years and impressionable. His long held belief, that he could arrive at some understanding with the Chinese leadership on the question of Tibet, has probably been shaped to a degree by this early experience.

But Taktser Rimpoche’s was a grown man, thirteen years older than His Holiness, and his experience with the Communists convinced him that China’s intentions regarding Tibet were malevolent. Rimpoche was not without some guile himself, and he managed to give the impression to his captors that he was receptive to their overtures. They decided to send him to Lhasa to win over the Dalai Lama. Rimpoche describes the unbelievably crude way the Communist leaders approached him promising to appoint him “governor-general” (chikyap) of Tibet if he convinced the Dalai Lama and the Tibetan government not to resist the Chinese advance into Tibet. They even went so far as to hint that if the young Dalai Lama got in the way he could be taken care off, and that Rimpoche might think about it doing it himself “…in the interest of the cause”.

Rimpoche reached Lhasa on the eve of the invasion and told his brother everything. His advice probably contributed to the young Dalai Lama and the Tibetan cabinet’s decision to leave Lhasa after Chamdo had fallen. When the Tibetan government and the Dalai Lama chose to remain temporarily in Dhromo in the Chumbi valley, Rimpoche decided to continue on to India. Once in India his old friend Tilopa Rimpoche (the Dilowa Hutukhtu) contacted him. He told Taktser that arrangements had been made through the Committee for Free Asia (a CIA front) for him to travel to the United States. This eminent Mongol Lama, who had survived Stalin’s purges, had been invited to the United States in 1949 as a resident scholar at Johns Hopkins University. The American who made this possible was the distinguished orientalist, Owen Lattimore, who was then a key consultant of the United States State Department’s Far Eastern affairs. It is ironic that someone who aided this Mongol lama and (indirectly) Taktser Rimpoche to escape Communist persecution should later became a principal target of Senator McCarthy’s infamous anti-Communist witch-hunts and face false charges of being a “top Soviet agent”.

Rimpoche didn’t have an easy time of it in the States, what with bad health, lack of English and insufficient funds. But he gradually learned English (at Berkeley) and even mastered Japanese when staying in a Japanese monastery for some years when the Government of India did not renew his expired IC and the American government was not helpful about giving him asylum. The CIA had lost their initial interest in him after the Tibetan delegate in Beijing signed the 17 Point Agreement and the Dalai Lama returned to Lhasa. Finally, after about three years his friends in the World Church Services secured permission for Rimpoche to return to the United States. He earned a modest income giving Tibetan classes to a handful of students as a part of a non-credited course at Columbia University, while his servant Dhondup Gyaltsen worked in a factory. I got the impression from his autobiography that Rimpoche spent his evenings in his small New York apartment making soup (most probably thinthuk soup) “…according to a typical Tibetan recipe”

This was at a time when Tibet was having its honeymoon period with the Communists and many merchants, lamas, monasteries, aristocrats and yabshi were reveling in the dayuan silver the Chinese were spreading around Tibet. Many of Rimpoche’s old acquaintances tried to convince him to return to Tibet including some of his own relatives, as he frankly mentions in his biography. But Rimpoche was convinced that the easy money and strident affability offered by the Communists was a passing phase and that there would be a reckoning soon. His younger brother Gyalo Thondup who had studied at a Guomindang school in Nanjing was also distrustful of the Communists and escaped to India from China.

When the Dalai Lama came to India in 1956 for the Buddha Jayanti celebrations, Rimpoche immediately flew to India where with Gyalo Thondup he tried to persuade his brother to seek asylum in India. Other Tibetan leaders in exile as the former Prime Minister, Lukhangwa, pleaded with the Dalai Lama not to return to Tibet. But in the end the Dalai Lama consulted the state oracle. The Dalai Lama mentions in his Compassion in Exile that Lukhangwa refused to leave the room even when the oracle became angry with him. The old aristocrat warned the Dalai Lama “When men become desperate they consult the gods. And when gods become desperate, they tell lies.” But the Dalai Lama returned to Lhasa.

A disappointed Taktser Rimpoche flew back to New York. By this time, fighting had broken out all over Eastern Tibet and Rimpoche was in regular communication with the State Department. He had also re-established his contacts with the CIA. In an interview he gave me he said that he later passed on all these contacts to his brother. He did not explicitly say so but I assumed he must have realized that Gyalo Thondup had the more conspiratorial bent and the diplomatic skills necessary to use these connections effectively to benefit the Tibetan cause.

Rimpoche assisted in the training of the first group of Tibetan agents (Athar, Lotse, Gyato Wangdu and others) in Saipan, acting as an interpreter. Rimpoche along with the Kalmuk Geshe Wangyal were also on the CIA team that devised a telecode system to describe items that were not in the Tibetan vocabulary and created a system of writing precise intelligible messages concerning modern warfare and intelligence, within an archaic traditional language. Rimpoche and Geshe Wangyal were also involved in the writing of training manuals for guerilla warfare, sabotage and so on.

Rimpoche’s language skills: Tibetan, Mongol, Japanese, Chinese, English and his native Sining patois, underscored his essentially scholarly nature, and he probably found the whole warfare and espionage world alien to his nature. He went back to his teaching, but he also started to organize relief effort for Tibetan refugees with his contacts in the World Church Services and other organizations.

Rimpoche initiated Tibetan studies programs at the American Museum of Natural History and also developed a similar program at Indiana University, where he received a professorship. He began teaching there in 1965 and as an old student of his told me “he had no trouble drawing students to his classes”.

What I have always found intriguing about this high lama, abbot of one of the most important Gelukpa monasteries, and a brother of the Dalai Lama, is that he was not interested in giving dharma lessons or starting a dharma centre, but instead wanted to let the world know about the culture, the history, the land and most of all the people of Tibet. This trait comes out clearly in his book Tibet, Its History, Religion and People, which he co-authored with Colin Turnbull. It is a wonderfully encyclopedic account of Tibetan history (especially folk history and cosmology) and Tibetan life, studded with all manner of legends, fables and (unusually for a history book) personal and intimate memories of Rimpoche’s own childhood, life and travels. The well-known cultural-anthropologist, Margaret Mead, called it “a uniquely sensitive and beautiful book”.

It could be pointed out that the book somewhat idealizes Tibetan life. But then again it never carries it to a point of dishonesty or absurdity, and is clearly an expression, a metaphor, for Rimpoche’s deep and genuine feelings for his people and country. I found the book so enchanting, so irresistible that I bought a dozen or so copies of the paperback edition in Delhi, and used it at TIPA (in the early seventies) as an English textbook for senior students, and as a primer for teaching them their history and culture. The book also had a wonderful set of drawings by the folk artist Lobsang Tenzin, of a variety of Tibetan costumes, household utensils agricultural implements, weapons, nomad encampment, and interiors of tents with everything numbered and identified. It was a cultural resource in itself. Even the paperback edition is now out of print but I think second-hand copies of the Pelican edition can be bought on Alibris or EBay.

Just the other day a friend of mine told me that the poet Woeser had written about Taktser Rimpoche and mentioned that she had come across Rimpoche’s history book in an official neibu translation. My friend translated this excerpt from Woeser’s blog:

“The first time I read the book was probably 1990. At that time I was newly returned to Lhasa: a sinicized youth, who knew almost nothing about her own people’s history and culture. In my circle and in the reading circles of quite a few Tibetans in Tibet that was the first Chinese translation of a book in which we could read about Tibetans and about the real Tibet. From that time on I regarded the book as a treasure; wherever I went I kept it by my side.”

Of course, Rimpoche was a spiritual person, perhaps even deeply so. He had been raised a monk and a trulku and his book is definitely not a secular history. But unlike many other Tibetan lamas and geshes, Taktser Rimpoche clearly saw that although religion was an important feature of Tibetan life, it was only one of the many features that defined the life, and indeed the identity of a Tibetan person. Rimpoche told me that although he firmly believed that his brother was the true incarnation of the Dalai Lama, he did not consider himself to be a special person spiritually. In his history book he candidly mentions that as a child he did not recognize any of the objects placed before him when he was tested. More than anything Rimpoche was an honest man. He absolutely detested those who went around claiming spiritual authority and accomplishments that they did not possess, and exploited the dharma for material gain. He himself refused to give religious teachings. In fact Rimpoche delegated another professor in his department to teach the required course on Tibetan religion for the Tibetan studies program.

It was always easy to talk to Rimpoche. You didn’t have to stand on ceremony with him. You never felt awkward around him, unsure whether to bow or prostate or receive a chawang. You just shook his hand, made a joke, or told him the latest gossip from Dharamshala. He also never patronized you like the great and powerful in Tibetan world generally like to do. I got to meet him and speak to him more often after I moved to the States during the late 90’s. And of course one of the main topics of conversation was rangzen and what we could do to promote the ideal, even in a small way.

Taktser Rimpoche, Sonam Wangdula, Thupten Tsering la, Lhadon la, myself and some others, who shared that concern and conviction, founded the Rangzen Alliance. Rimpoche hosted the first Rangzen Alliance Planning Meeting at his Tibetan Cultural Center in Bloomington Indiana, on November 23-24, 2001. Two of us (accompanied by Peter Brown) also set out on a Rangzen Road Trip driving across 28 states, five provinces (in Canada) and the District of Columbia for about a month to contact as many Tibetan communities, individuals and friends to reenergize the struggle for Tibetan independence that was weakening with each passing year. Rimpoche gave us an enthusiastic letter of support that we sent around to the various communities to introduce ourselves and our mission.

Rimpoche had his faults, of course, and his share of detractors. One of the usual criticisms against him was that he had stayed away from the Tibetan world and had not worked in Dharamshala for the exile government. There was some truth in that charge, although Rimpoche served (very briefly) as the Director of the Tibetan Library and as the Dalai Lama’s Representative in Japan. But these were short stints. I know that some of his yabshi relatives also held that against him, as in fact I did for some years.

But if I were to argue on his behalf now I might say that the very distance he maintained from the exile administration and exile world, allowed him the intellectual freedom to hold on to the ideal of independence. If he had served in Dharmshala, where absolute conformity is the minimal requirement for holding any kind of high office, we might have another failed negotiator in the long list starting with Gyalo Thondup and Lodi Gyari and ending with God knows who. But the rangzen struggle would have lost a mentor and a comrade-in-arms.

As is it is, even out in the wilderness, the yul-thakop of the American Midwest, Taktser Rimpoche was able to keep alive “the embers of rangzen” and pass on to us his conviction that Tibetan independence was absolutely not negotiable, and was (as mentioned earlier) a fundamental condition, an essential requisite for the survival of the Tibetan people, their language, their culture and even their religion. There was no other way.

In late 2002 Rimpoche suffered a series of strokes and became an invalid. The last time I saw him a year ago he did not appear to recognize me. Yet somehow he was still with us, when in March this year the rangzen revolution happened in Tibet, and Tibetans everywhere around the world challenged Communist China occupation of Tibet. People close to Rimpoche told me that he did seem to appreciate the significance of the events. And at least his presence was there at the Freedom Torch reception ceremony in June 2008.

Rimpoche was present at the conclusion of another event, the Freedom March in Philadelphia last Fourth of July. I heard this recording made by a Radio Free Asia correspondent, Karma Gyatso, where someone was trying to get Rimpoche to say a word or two for the occasion. Of course Rimpoche’s speech had been near completely impaired by the stroke, but he made a great effort to say something. It was just two syllables, very indistinct, murmured again and again. It was not at all clear, but if you listened hard, it seemed like he was repeating these two syllables “hrrm-hrn … hrrm- hrn … rang-zen.”

tashi delek,

I hope you dont mind, that I put this page on our website (friends of Tibet) in flemish Belgium

Georges Timmermans

alias (karma webmaster)

Thank you Jamyang-la so much for this very moving tribute to Taktser Rinpoche. Those who knew him well will know that you have succeeded in capturing his character and spirit so much better than all those journalistic stories. He is missed very much. I personally have so much to thank him for, I can’t even begin. One of the things he liked to say that comes back to me now, “To tell you the truth, the very last thing I want to know about people is which religion they belong to.” He really meant it. Not just that some of his best friends were Catholics or Muslims or Agnostics. They *were* his best friends. He detested religious hypocrisy and double standards as much as I did. And do.

I had the privilege of spending a few very very memorable days, with Taksar Rinpoche in 1997, for his walk for Tibetan Independence from Toronto to New York. At that time Rinpoche already had his pace maker and could only walk slowly… but he walked… for about 90 days, and spoke of Tibet and Rangzen, in his gentle manner, all the way to NY. This was just one of the many walks Independence that his took part in over the years.

In his life he lovingly sowed the seeds of Rangzen where ever he travelled, and in that he ensured that it will definitely bear fruit.. someday, and the Tibetan people and culture will survive.

Bod Rangzen

Dear Jamyang La,

One of the best tribute ever written to late Taktser Rinpoche,very sensitive and authentic. It was like seeing a flash back of Rinpoche’s life and his dedication to Rangzen cause. Great piece! Thank you Jamyang Norbu la. May every tibetan will keep some memory of Rinpoche’s dream and deeds in their heart to fuel our inate desire of Rangzen. Free Tibet.

Jamyang la,

As American teenagers would say….AWESOME. What you wrote up there made me wish I had met Taktser Rimpoche. I am going to read his book after I finish Machiavelli. Rich, instead of that Chinese guy’s art of warfare, I am reading Machiavelli’s The Prince and THe Discourses. I appreciate your advice.

Jayang la, Thank you so much for sharing your thoughts and specially about his holiness Taktser Rinpoche. We will keep the spirit of Rangzen alive until we die.

I salute him! I salute a person like you! i salute all the freedom fighter for the Tibet cause!

I really learnt so much from your blogs. I will wait for your upcoming blog.

TIBET WILL BE FREE SOON!!!

Thank-you so much Jamyang for your frank,powerful tribute to the One&Only (so dedicated/brave)Takster Rinpoche.I so appreciate getting to read your heartfelt account and it is so on the button after the transit of this rich herioc true soul who labored long and hard for his beloved people, for a just cause.

Many thanks from Nohar

“But if I were to argue on his behalf now I might say that the very distance he maintained from the exile administration and exile world, allowed him the intellectual freedom to hold on to the ideal of independence.”

Doesn’t it make it harder to hold on to it when you are living away from the exile world, to strike a balance between assimilating into a new culture and holding tightly to your own?

Aravinda, welcome to the crowd of barefoot experts. Anyone can ask a purely theoretical question like that, but the fact that you did shows that you have little or no experience and done little or no research into the matter.

Hullo Jamyangla

Interesting!

I am also more interested in the case of the mob rising that you mentioned in the first paras…

This is the second instance I have heard of this peculiarly Tibetan mob mentality against (mainly intellectual?) folks who think differently.

The first I heard was Dawa Norbu…

Why do we do this?

Dear Gen Jamyang la.

I am deeply moved by your detailed and clear tribute to Taktser Rimpoche, may he be back with us with greater lights as soon as possible. Om Ma Ni Padmah Hung.

Thank you Gen Jamyang la, for writing this touching article, it has sharpened so much of my wonders and doubts about the undiscovered past. It is such an inspiration and encouragement, even rises in me a bit of pride to be Tibetan, knowing that so many of our for generation has been and will be putting tireless effords, hearts, minds and souls, in order to keep our Tibetaness Alive. Like His Holiness the Gyalwa Rimpoche, and thousands of other Tibetans and non-Tibetans,who are the bright lights in these dark ages, you too 9 Gen Jamyang la, is providing me and for many thousands of Tibetans, for many generations the light of insight.

Though some of our people have different approaches, we all know and will stand firmly United as Tibetans.

Differences is what creates our Tibetan Unity.

May we be Free in Our Land Today

Patel never have good pleasure of knowing deep holy man Takster Rinpoche. However can really revel in his holy presence as real freedom fighter who clearly know reality of China mind –mind of lying insincere deviously.

Jamyang made such nice tribute which is very much glorious for us to share in.

Would be nice to write book chronicling history of all freedom fighters devoted chapter to each and call “Torch of Freedom: Rangzen and Resistance,” or “To Slay the Dragon” or “River of Blood, Ocean of Wisdom” to tell story of Tibetan and Khampa fight for His Holiness the Dali Lama.

Patel like to write this book but English not so good and history elusive in my the knowledge.

Returning to point, Takster Rinpoche real embodiment of Buddhist spirit of never back down from right way and truth…real truth insistence…so sad he passed without my chancing to be knowing him.

Well, there is a tendency to idolize people. Let just get it right, Taktse was a freedom fighter. Keep it that simple. When add holy, rinpoche, and so forth numerious religous title. These titles are destroying Tibetan movement.

One of the best pieces I’ve read on this blog. Other being Long March Homeward. If you’re thinking to publish future collection of your latest writings, be sure to include both of these essays in the first two chapters.

Also Karmapa and the Crane makes a very intriguing read. Three of them best of all, not to metion running-dog progandists and barefoot experts, plus essays on golstein. All of them if compiled will become a book. Plus the one which is coming up on Tibetan Films. I will be the first one to buy. Thanks.

Dear Tsenpo, No. Taktser Rinpoche was anything but a simple person, so keeping it simple just won’t do. I very much doubt you knew him. Calling him Rinpoche won’t kill you or harm the Tibetan movement even in the least. And Rich. Why so rude? Why now? What’s wrong with you? Not the time. Not the place.

Tsenpo

I agree with you entirely, but not sure about the motivation behind the strange comments of Sharma Patel.

Patel like old Zen man from Japan and having motivation of no motivation! Meaning is the meaning. I having full right to call holy man holy man. Have big insider knowledge on who being holy. Not a state secret you see. You having full right to object with opinions. Title not destroying Tibetan movement. Lazy bum sitting destroying Tibetan movement. Motivation of no motivation means big motivation. Rangzen! Wish all tulku-rinpoche-lama-guru ji-khenpo-mahatma-lotsawa will be off lazy bum now! Wish Tibetan people in freedom and prison and exile and everywhere will be off lazy bum! Dont you worry about Patel motivation but be checking to your own. What you doing to Free Tibet if you have red Tibetan blood?

Of course religious man in dangerous territory on this blog is it? No matter because my big motivation of no motivation means also not afraid for anything anymore.

Title-paper of Rinpoche is good when run out of toilet paper isn’t it? But Takster Lama was really a precious jewel, and that is only point of Patel. You clear?

Big motivation is willing to pay any and every price. Big motivation is willing to suffer indefinitely. Big motivation is knowing life and death just one. Big motivation what we all need. Big motivation opposite our steamy wind breaths. I need. You need. Big motivation is hardest thing in the life of human being.

Big motivation is to be knowing that expression of natural order (Rangzen) will not come naturally or from diviine intervention but by human heart and hand in ACTION.

Big motivation is to fight without fear hatred or even desire because to fight is the expression of rightness goodness and mercy.

These days almost no lamas nor freedom fighters have the big motivation like Takster Lama had.

Really Rangzen need religion desperately to succeed. Religion need Rangzen desperately to succeed. Why? Because unity in Tibetan movement without religion will not be happen. And surviving religion without Rangzen will not be happen. Scholar boys can taking the offence – no matter – Patel said the factual.

As for Titles stockpile title papers for deforestation problem and make good kindle for fire and good toilet paper. Rinpoche not made by title but inside his heart. Takster Lama was real Rinpoche.

Thanking you for the partaking with my poor English. Please do be checking my motivation whenever you are taking rest from freedom fight.

Winkingly Yours,

Sharma Patel

This article inspired me deeply.

Honorable Jamyang La,

It was a great eulogy for the person worthy to be and you put it very well. Thuk Je Che!

I did have the pleasure to meet Him at Woodstock, New York in 1997, when He was marching form Toronto with his companions. I was doing seminar at Camphill School for the mentally handicapped adults there at Copake, Upstate New York. I was new to the country and Lama Pema la, whom by chance happen to be near my school and who has also befriended with some of our teachers there, welcomed me to be presented at the dinner. I was making tibetan food for the marchers at one of his student’s house. I was so intrigued by his simplicity and his undaunting struggle for Rangzen made my day as a tibetan who can do something about it.

I started reading lot of books, anything to do with tibetans in it, thereby I was able to give some talks about it to some nearby schools. I came from a freedom fighter’s home, but the talk was only limited to adults with secret meetings at our home and that I was meant to do well in school is all I must concentrate.

Our Late Takster Rinpoche la, he gave me the spark to my everyday thoughts on Tibet. For this I raise my glass for His soul to journey well into the realm of Boddhisatvas and may His works flourish brightly as ever and one day we will have a free country so we don’t to have live as refugees anymore.

Free Tibet!

warm regards,

Dolma Tsering.

** I was wondering if you have any idea when will the fifth and the sixth volume of the book “Resistence”- written by Kasur Lhamo Tsering la coming out?

I had the honour and good fortune to meet and talk with Taktser Rinpoche in Delhi just when he retired from his post in Japan. Although, he may seem to have avoided being amidst our administrators in Gangchen Kyishong, he showed great courage and care, concern, love for the Tibetan people by accepting the post of Representative in Japan which was a hot seat heated by the outgoing Representative Pema Gyalpo Gyari.

The day I have received news of the demise of Taktser Rinpoche, I re-read his book Tibet my country and in my heart prayed for his bereaved family members.

Talking of first Rangzen marcher (T.R marched in USA) reminded me of a young and dynamic first Tulku Rangzen Marcher in India, in the name of Shingza Rinpoche. He is reincarnate of mother of Je Tsongkhapa, the founder of Geluk Sect. He lives and studies in Sera Monastery.

When American people (and world at large) wait impatiently for the result of U.S President,let’s think, discuss, participate and hope for changes in policy in our own exile government. Let’s unanimously, courageously and openly SEEK Rangzen. As Shingza rinpoche wrote in Tibet Times : ONE GOAL

ONE CALL

ONE STRUGGLE – RANGZEN !!!!!

Tsenpola, have you ever heard of battle being won or lost just because the enemy calls your commanding officer – Sir? Likewise, it ‘0s naive of your to say that using titles destroy tibetan movement. Our movement is diluted for the lack of sound thought, correct thinking and lacking virtue to accept people whose opinion differs from you, taking ideological differences as personal and attacking them, exactly what Jamyang Norbu la talks about and what Dechen la asked about “mob rising”as she said has heard first time in case of late Dawa Norbu la.

It may be “COOL” in USA to call everybody with first name but we do not have to ape americans always. We take the best of all cultures in the world while retaining our good culture as well and shun unwanted ones. Grow up man! If a Rinpoche lives upto his title, as Taktser rinpoche did, then lets use his title with his name as befitted.

Hello JN la,

I´ve bin reading ur book (shadow tibet). and its really interesting! specially when it comes about our unsung heros! and then i thought why didnt i hear about these before! I never hear about them in our school in detail, but why not? it´s something to be proud of, not to be ashamed or hidden. These are somthing our students should hear regularly. So i ve a Sudgestion/Request for u. That is u privately or RTYC should make a journal called Rangzen or something u choose and inside people write only about rangzen! no adds no bullshits! ll be great if theres autobiographys from our unsung hero´s like Dzazag Gompo Tashi, General Wangdu,Athar,Yunri Ponpo,and Dorjee Youdon from Gyaritsang every week to read! that ll defenately keep all the young ones inspired n they study harder. thats how there ll be lot of follower for RTYC.

Im sorry if it sounds bullshit but i have to tell u because u r the only one whom in my knowledge is open n staight. BOD GYALO!!

A sad moment. I’ve just learned of the death last year of Norbu-la. I met him in 1960-61, when he first arrived in Seattle to stay for a while with the Sakyapa family. (My then husband studied Tibetan at the University of Washington and we helped to settle the family in the U.S.)

Norbu-la was a charming, handsome man – my women friends jokingly called him “Tibet’s gift to women”! But he was also very serious in his work and intentions.

I last saw him about 20 years ago, when he visited Berkeley and we reminisced about the times when we were young and had hopes of changing the world and seeing Tibet a happy country that could enjoy the advances and benefits of 20th century life without losing the centuries of tradition that led up to it.

As I said, a sad morning filled with good memories of old friends.