The Anabasis of Xenophon – not to be confused with Anabasis Alexandri, the biography of Alexander the Great – is the story of the epic retreat of a Greek (mercenary) general, Xenophon, and his 10,000 men from Persia back home to Greece. It is a gripping adventure story and a fascinating travelogue, where often Xenophon’s own observations provides much that is picturesque and fascinating. For example, he comes across an underground village in Armenia, whose drinking habits he describes:

“There was barley-wine in great bowls. The actual grains of barley floated on top of the bowls, level with the brim, and in the bowls there were reeds of various sizes and without joints in them. When one was thirsty, one was meant to take a reed and suck the wine into one’s mouth. It was a very strong wine, unless one mixed it with water, and when one got used to it, it was a very pleasant drink.”

For a brief moment – quite brief, because I knew the Greeks (later, under Alexander) never made it further east than the Punjab – I wondered if Xenophon and his men hadn’t somehow lost their way and ended up somewhere in Kalimpong, Sikkim or Darjeeling. But following that fleeting moment of silliness, I slipped into this reverie of my youthful days in Kalimpong in the late sixties, when I spent a great deal of time at the Tenth Mile at Kalimpong sipping (through a bamboo reed) that warm and wonderful fermented millet drink that Tibetans and Sikkimese call pahi, Lepchas call ché, and the Limbu people (aka Yakthumba) call tongba, and by which name it is known to the Tamang, Rai and some Nepali speaking people. In Bhutan it is called ban-chang, a term that also covers other types of fermented drinks.

This drink is made from the red finger millet that Indians call ragi or murwa, Nepali kodo and Tibetans and Bhutias, monchak. The millet is first of all scrupulously washed, sometimes partially de-hulled with a wooden pounder, then it is cooked thoroughly and the resultant mash is laid out on a clean sheet of cotton or plastic and left to cool. When the mash is warmish, brewer’s yeast called phap or chang-tsi (Tibetan) sold in white round cakes at the Kalimpong hart market, is crushed into powder and spread evenly over the mash. There is a belief among professional Tibetan brewers, mostly women (chang-ma), that certain children have lucky hands, and their services are sought to spread the yeast. They are rewarded with candy or cookies, of course.

The mash is then tied tightly in a plastic sheet and put in a large bucket or pot and sealed. The container is often swaddled in old blankets to keep it warm. Then the mash is allowed to ferment for a week or two. Sometimes the mash is carefully stored away and allowed to slowly ferment for a whole year and is then called the lo-chang. In Sikkim there are pahi connoisseurs who not only store away their pahi mash (bangma) for over a year, but even to a point where little white grubs form in it. It is said to be a especially nutritious beverage, but I must admit I’ve never had the pleasure of drinking it.

But generally when the fermented mash (bangma) is ready after a couple of weeks it is ladled into a wooden or bamboo container about 11 inches high and 4ins in diameter, called pa-shing in Tibetan and dungro in Nepali.

Since the mash is an inauspicious dark-brown in color, a few grains of white rice are sprinkled on top to correct the situation. Then hot water is poured from a kettle into the bamboo container, and the pahi is left for at least five or ten minutes to settle and infuse. A bamboo reed-straw called chip-shing (sip-stick in Tibetan) and domo in Sikkimese is stuck into the pahi. The bamboo straw has a slit at the bottom through which the liquid enters and the flow is sometimes regulated with a little sliver of wood through the slit. Before drinking there is this custom among serious drinkers of sticking the straw into the pahi and, covering the top hole with a finger, lifting the straw out. Then the straw is turned upside down and the liquid in the straw allowed to pour out on the floor. This rinses the mouthpiece and also serve as an offering to harmful spirits nearby.

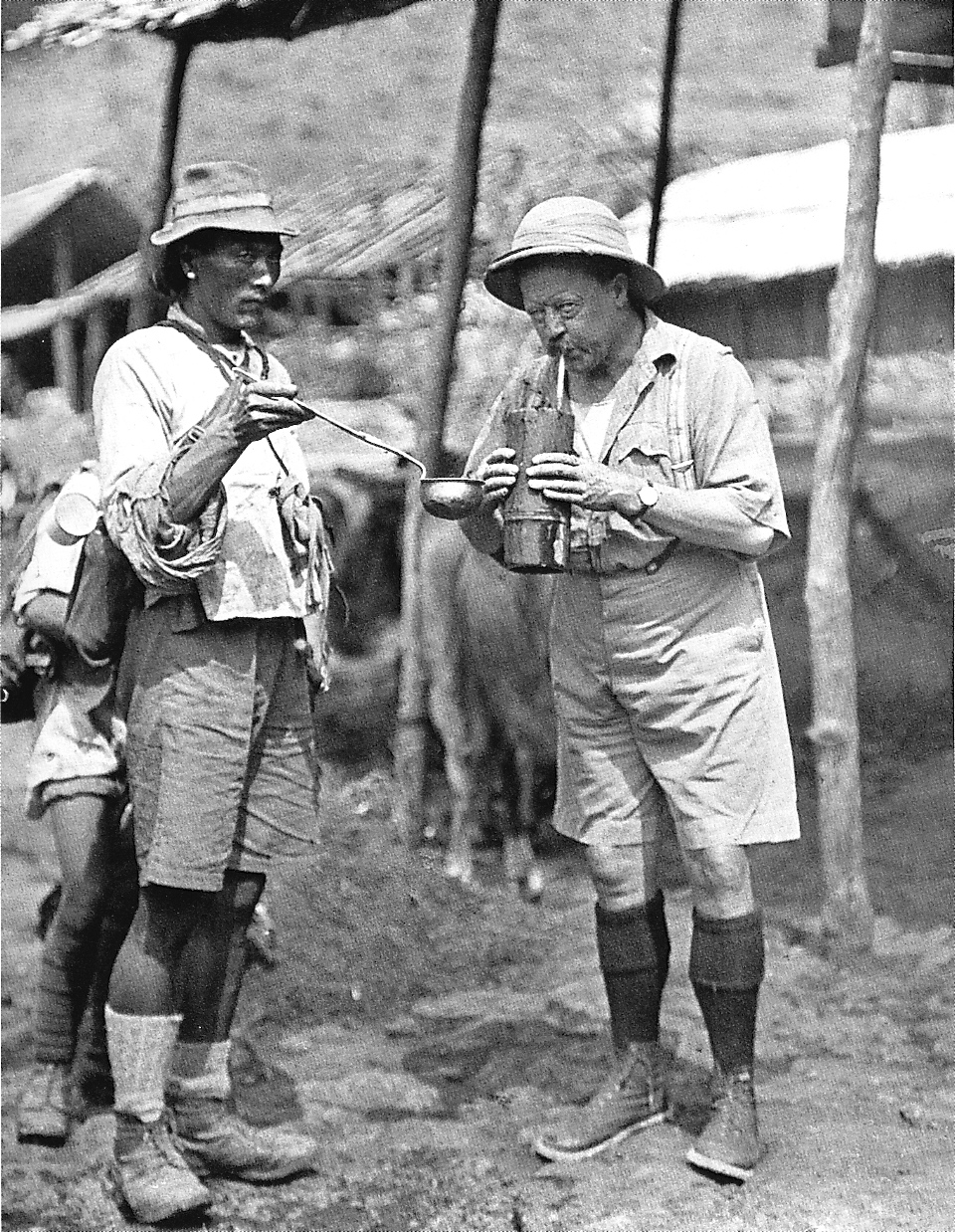

Sarat Chandra Das in his book on Tibetan grammer reproduces a drinking song “The Song of the Precious Reed (nyungmae nyung-shay)” from the region of Tsari in Southern Tibet where the millet pahi is drunk. This millet chang is also drunk by Tibetans in the district of Pemakoe, also in Southern Tibet. Interestingly enough the ethnic Qiang people, living on the eastern edge of the Tibetan plateau and speaking a Tibeto-Burman language, also drink their native zajiu wine through reed straws.

The custom of drinking pahi communally like the Qiang is sometimes followed by Tibetans and Sikkimese, especially at parties and picnics. A large pot is filled with the pahi mash and about six or more pa-shing straws are stuck into the container, for everyone to join in. This custom is called zur-druk or six corners.

Young people in Darjeeling or Kalimpong when going on a date, especially to restaurants with private curtained booths, might order one pahi and ask the waiter to stick two chip-shings in the container. Then the two might lean forward to share the drink and sometimes touch foreheads.

I say without reservation that the pahi is for me the most delicious and heady of light alcoholic drinks. It has the soul-warming virtue of good sake, but also a subtle fruity flavor that I am quite unable to pin down. Early English travelers to the Himalayas all seemed to have enjoyed the tongba but were never able to agree on what it actually tasted like.

David Field Rennie, 1866 : “Their intoxicating drink, which seems more to excite them than to debauch the minds, is partially fermented Murwa grain …. The fluid, when quite fresh, tastes like negus of Cape Sherry.”

Edward Balfour, 1873: “…the fermented juice of the murwa grain gives a drink, acidulous, refreshing and slightly intoxicating, and not unlike hock or sauterine in its flavor.”

Joseph Dalton Hooker (the great botanist), 1854: “For drink we had a large bamboo jugful of the refreshing beer, that the Lepchas brew from a millet seed called Murwa. The fermented grain is put into a jug.. filled up with hot water. The liquor is imbibed by sipping it up through a thin reed like a straw. It tastes like weak whiskey-toddy or rum-punch with a pleasant acidity.”

Speaking of Himalayan travelers, I mustn’t forget to mention the role of the tongba in mountaineering history. The first British expeditions to Everest (1921 & 22) not only had the blessing of the 13th Dalai Lama and an official Tibetan travel permit (lamyig), but also appeared to have been well fueled with tongba all the way from its base in Darjeeling.

In the old days the best pahi was unquestionably the one from Kalimpong. Darjeeling and Gangtok pahi were very good, but not the divine nectar brewed in that old caravan town. The industrious Tibetan craftsmen of Tenth Mile, who manufactured incense, phing noodles, saddles, silverware, Tibetan boots, saddlebags, backpacks and bags of every kind, would, in the evenings relax with a couple (or few) well-deserved pahis. The compassionate ama chang-ma of 10th Mile who created this wonderful brew and generously served it to us lowly mortals, are all gone now, but at least I have my memories of them. These days most Tibetans have left that town and the local Gurkhaland politicians have resorted to blaming the few remaining bhotays for corrupting their youth with tongba. So two years ago when I went to Kalimpong I found it impossible to get a drink. Even the stuff still being made these days in Kathmandu and elsewhere is really not very good. The brewers now use adulterants to speed up the fermentation, which effects the taste and gives you a headache afterwards.

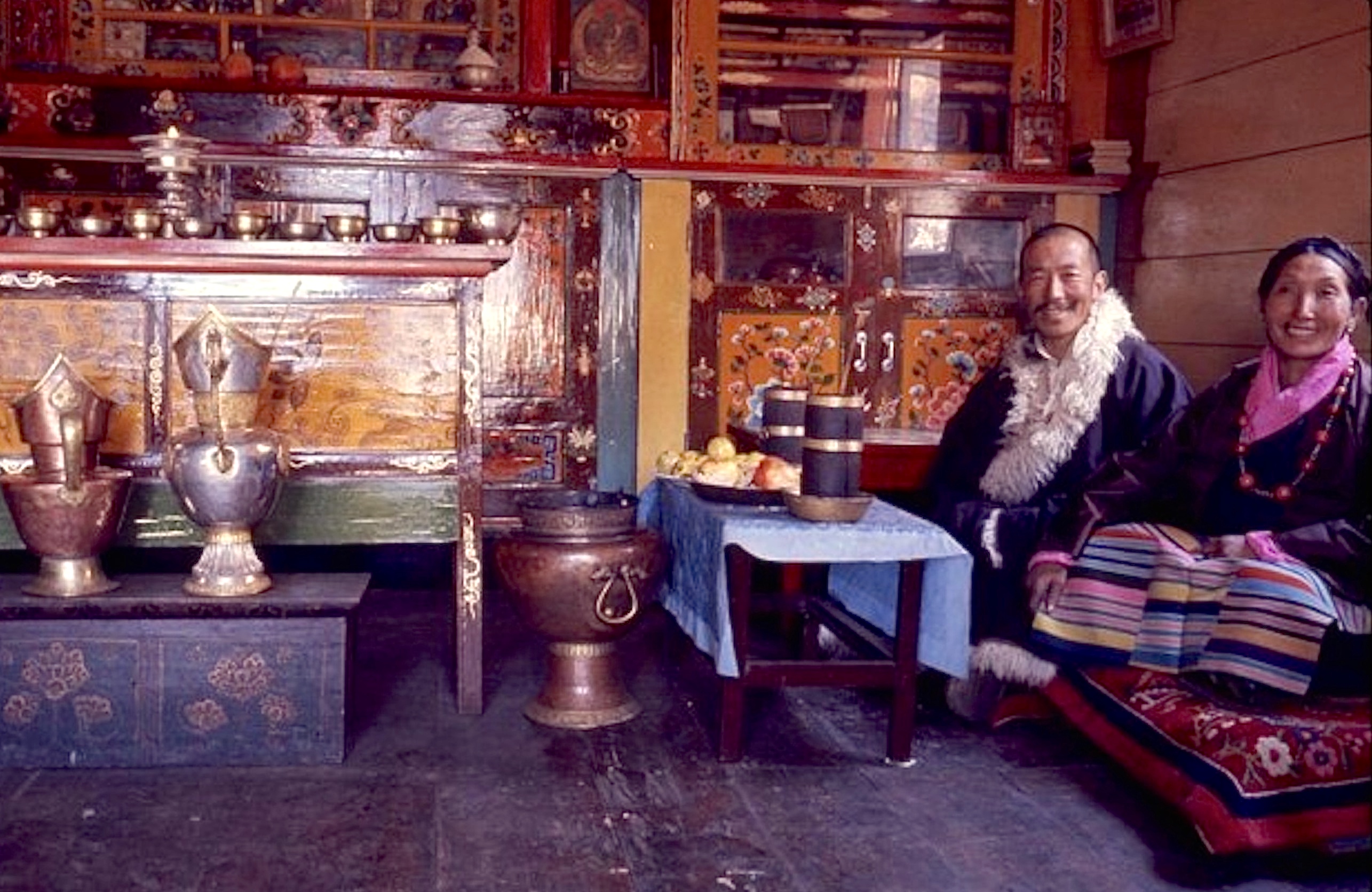

I remember this humble chang-khang tavern at the intersection of the main 10th Mile Road and the road to Tirpai. Just above the communal (PWD) water tap. It was run by this amala and her pretty daughter, who not only made the most incredibly divine pahi but also had an endless stock of sha-kambo (beef jerkey) and flaming hot sauce. The drink and the snacks were clean, eminently affordable and always served with a smile and sometimes a joke or a tease. On this auspicious day of our Losar I request my Kalonbooba, Denzongpa and Dorjeling-nga friends, and all pahi oenophiles, to join me for a drink at this special locale within my “memory palace”. No. No. Please, I’m buying. Amala, don’t take their money, its all on me. Tashi Delek Phuesum Tsok, Everyone! Next year we will be going back to Lhasa, and by way of Tenth Mile, Kalimpong, of course.

(I must thank Anna Balikci Denjongpa and Tempa la of Himalayan Heritage Art for information and help.)

Next year in Lhasa .. cheers to that Genla!

A wonderful timely piece. A joy to read. I had my share of this nectar in Sakya Shicha.

Thank you Jamyang la.

I wish you and your family a happy Losar.

May your works blaze forth like Jamphelyang’s Raldri.

very interesting to read all this. It seems Kalimpong really was like the “Casablanca of the East” in those days.

Losar Tashi Delek!

My daughter attended 4 years of Shedra at the Ka Nying Shedra in Boudhanath. She stayed at the home of our Lama and there living is a Tamang family. The mother of this beautiful fun family made a batch of Tongba specially for me when I would come to visit my daughter. When I try and describe the effect of this drink to my friends here in the States they think I am whimsically exaggerating. No hangover, but more incredible is the light and jolly effect it has on one’s constitution. The only comparison I can make to any thing here is a can of Fresca with half of the carbonation…but much better. Losar Tashi Delek!

It’s all new to me except the procedures of fermenting Chang. What a great read! Again thank you Sir for the interesting piece. I on behalf of all the readers wish you a very Happy Losar.

Chang – Good, Bad and Funny: Some of my observations

As a young boy growing up in India , I saw a dark side of this communal Pahi .

Tibetans used to drink in same communal style like one shown in pictures JN’ has above of the Chinese. While most of the men would share the big Pahi with lot of bamboo or aluminum ” cheb-shing” – sucking straw, people who are considered as lower caste are given separate Pahi.

Though to the discriminated guy’s advantage, it is more hygienic for him, but even a child in me (then) can plainly see the discomfort of the class discrimination.

Also, as a kids, unnoticed by elders, many of us would go around and eat fermented chang when it is laid out for cooling.

Also, I have noticed how some men whose wives don’t allow them to be sucking or drinking more than one Pahi a day, would always look for opportunity to empty half of their Chang into a cow’s feeds, whenever their wives are not around and quickly refill it with fresh Chang and pretend as if they are still sucking the same old Bhangma (used up Chang) that their faithful wives have prepared.

Also we should remember how this Tibetan “import ” in Delhi Majnu-katila has wrecked the homes of how many poor rickshaw pullers. Though we can say much of it is personal responsibility, but the extend of harm is so extensive that Indian social organization took up the issue as social evils.

Head of the Indian Women’s Welfare Society boss of the area in MT came to seek my help once. On her daily basis, she was quite a high official in Delhi Transport Department but also happens to be pious Indian Buddhist. She was torn between her social activism and fellow Buddhist feeling with Tibetan Chang sellers.

She even suggested whether people like me can educate our Chang ladies not sell more than one Pahi /bottle and send the poor rickshawalas out of the camps after one round.

I thank JN for his all wonderful work. I write this as I sit to enjoy my Losar Chang-koel my wife has prepared. I don’t touch Chang. But I will offer three Losar cheers to JN and his family.

Behind the success of every great man, it is said, there is a woman. Doctor Tenzin la, thanks for letting JN work for Tibet. Tashi Delek.

Jamyang la, thank you again for an enlightening article on Pai/Tongpa. Since it is Losar, I was wondering if you had any article on the lowly Chang-ko.

I make a small batch every Losar. I believe there are basic two steps; make or prepare the rice chang, and when ready take a small batch of the fermented Chang slosh and make the Chang-Ko soup. There may be a hundred other steps and ingredients and special flavours I am wondering?

I find this blog one of the most resourceful blog for public discussion.

I am planning to write a biography of Sikyong and looking for an appropriate title for the book. Can you folks help me what title I should have for the book?

Any help is much appreciated.

Oh how exciting, a new book about Dr. Sangay! It’s about time. There seems to be no clue as to the author’s motivation for writing this book or who his target audience will be. But be that as it may, I have some modest suggestions for a title.

Grandiose

THE KING AND I

Detractor

KING RAT!

Avid Fan

SIK-KONG!!

Imperious

I,LOBSANG SANGAY (I,Claudius)

Mysterious

THE MAN FROM NOWHERE

Pro-china

MIDDLEMAN

Anti-China

THE ANT WHO DREAMS OF RAPING AN ELEPHANT

Poignant

I HEARD THE CAGED BIRD SING

Upbeat

MISSION POSSIBLE

Disney

THE LOB BUG

Children

DOCTOR LOBSANG SANGAY AND THE GIANT PEACH

I thought up few more titles for the Sikyong’s book narrative…

Anti-Terrorism

WHY ORGAN HARVESTING LIVING PRISONERS ISN’T SO BAD WHEN ONE CONSIDERS THE ECONOMY OF THINGS. (Title shortened for the Enlightened Western readers) IF THE MONEY IS THERE, WE DON’T CARE!!

Psychology

THE MAN WHO MISTOOK HIS HAT FOR TIBET

Post-Colonialish

I LIKE TO BE CALLED LHAMO FROM NOW ON

Pro India

I ONCE DATED SMRITI IRANI

Social Media

SANG-ROID!!

Conciliatory

IT TAKES TWO TO TANGO

A HOUSE DIVIDED

THE JOYS OF BENDING OVER

Futuristic

BLUE MOON

Cooking

THE LAST OF THE SHAKUMPOS

Food and Travel

DELICIOUS EXPERIENCE: How I spend two glorious days in beautiful Guizhou, China partaking in the traditional Dog-Eating Festival.

Vaguely Disturbing

YEAR OF THE SHEEP, TEN MORE YEARS OF ME

Candid

CONFESSIONS OF A TIBETAN OPIUM EATER

Religious

THE WORDS OF MY PERFECT PROFESSOR