(A week or so after Phayul published Freedom Wind Freedom Song, on May 20th 2004, I received additional information from friends and supporters regarding the National Flag which I included in a follow-up piece. I have now added more recent material and am posting this new version of that article.)

A few days after the appearance of my essay “Freedom Wind Freedom Song” on WTN and Phayul, I received an email from the late Tendar-la, formerly an official of the Department of Information and International Relations (DIIR), who later served at the Office of Tibet, New York. Tendar-la was a hard-working, woefully underpaid civil servant, unswervingly loyal to the Dalai Lama and the Tibetan government but friendly and forthcoming with Tibetans who had differing views. I knew him when he was a little boy at Kalimpong Central School for Tibetans where I taught and coached the soccer team for a few years.

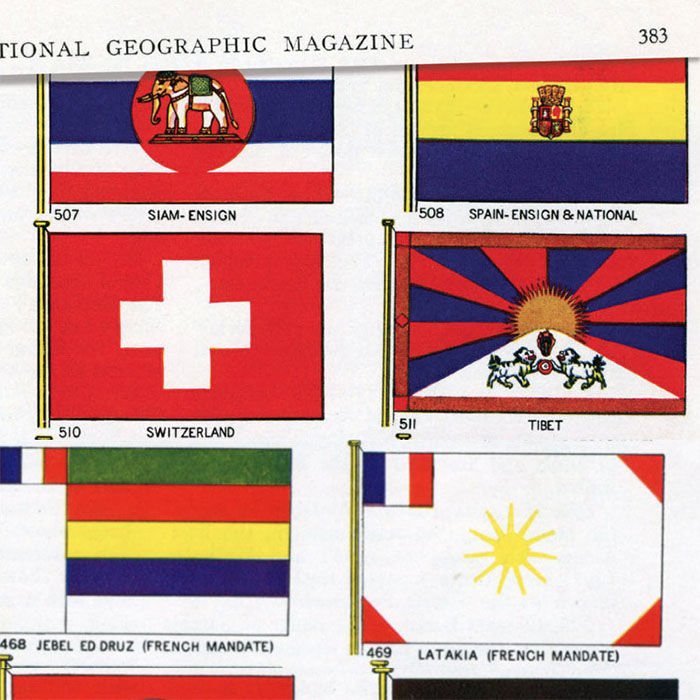

He wrote to tell me that the DIIR had, some years ago, been given an old issue (1934) of The National Geographic Magazine, which carried a reference to the Tibetan flag.[1] I managed to buy a copy on eBay and flipped to the main article, “Flags of the World”. And there it was on page 383, the national flag of Tibet, looking exactly as it does these days.

It was between the flags of Switzerland and Turkey. The description was straightforward: “Tibet. — With its towering mountain of snow, before which stand two lions fighting for a flaming gem, the flag of Tibet is one of the most distinctive of the East.” Most probably the National Geographic Society had obtained the Tibetan flag from Tsarong Dasang Dadul, the commander-in-chief of the modern Tibetan army and a member of the Geographic Society.

There was no mention that the Tibetan flag was a new one or that Tibet was a new entry in their list. The editors had, in the case of some other countries, made qualifications where necessary. In the case of the German flag the editors had been careful to mention that the Swastika flag of Nazi Germany had been adopted a year earlier as the German national flag by a special decree of the Chancellor, Adolf Hitler. A special reference was also made in the case of Manchukuo (or Manchutikuo): “The Kingdom of Manchutikuo came into being just in time to permit a flag to find its proper place in our plates.”

It might be mentioned that such entries as Cambodia and Annam were clearly noted as protectorates of France, or in the cases of Lebanon and Syria, that they were French mandate states. Even the old flag of Korea (then Chosen) was grouped together with Japan, and mention made that the Japanese flag had replaced this old Korean flag. No such qualifiers such as “protectorate”, “tributary” or even the British Foreign Office convenience term “suzerainty” were used to describe Tibet.

Of course, the 1934 issue of The National Geographic Magazine did not carry the flags of India, the Philippines, Israel, Ireland, Libya, Singapore, Indonesia, Burma, Nepal, Malaysia, Mongolia, Bhutan and many other present day nations, that had not become independent then. Even Australia and Canada did not rate separate entries as nations but are grouped together under the British Empire. The magazine listed 77 independent countries (Tibet being one of them) in 1934.

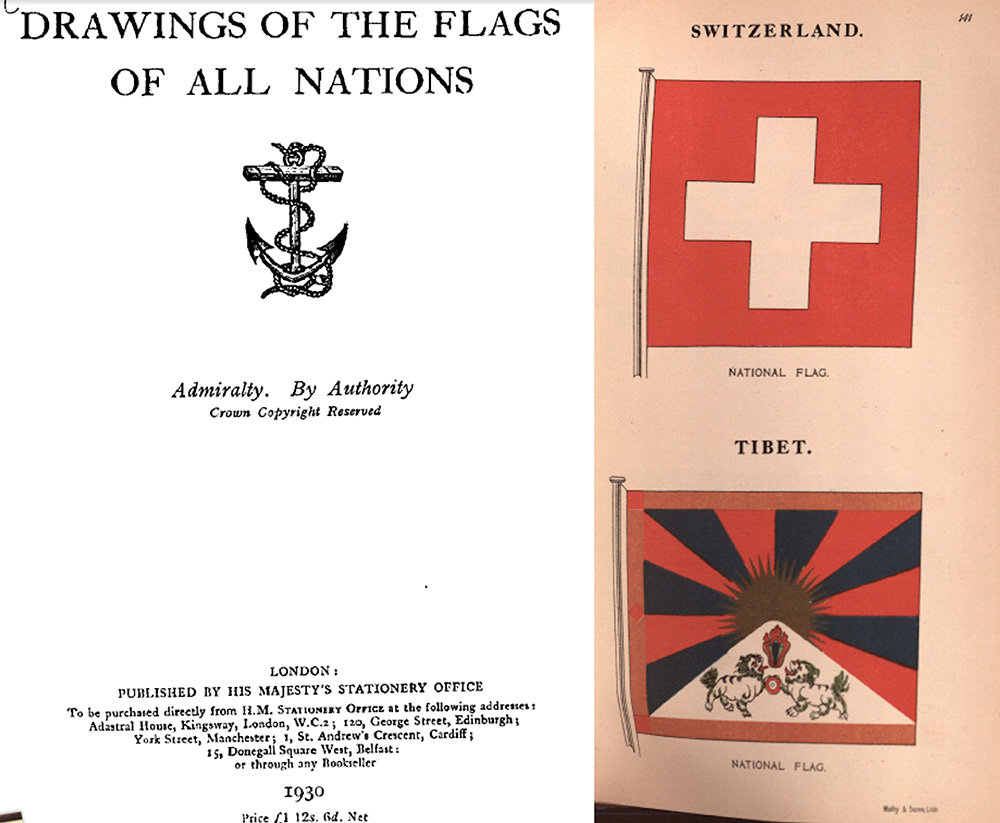

Some months after I had posted this article on Phayul, a German scholar on Tibet, Isrun Engelhardt, let me know of an even earlier catalog, an official British Crown publication of 1930, Drawing of The Flags of All Nations [2] where the Tibetan National Flag was first introduced to the world.

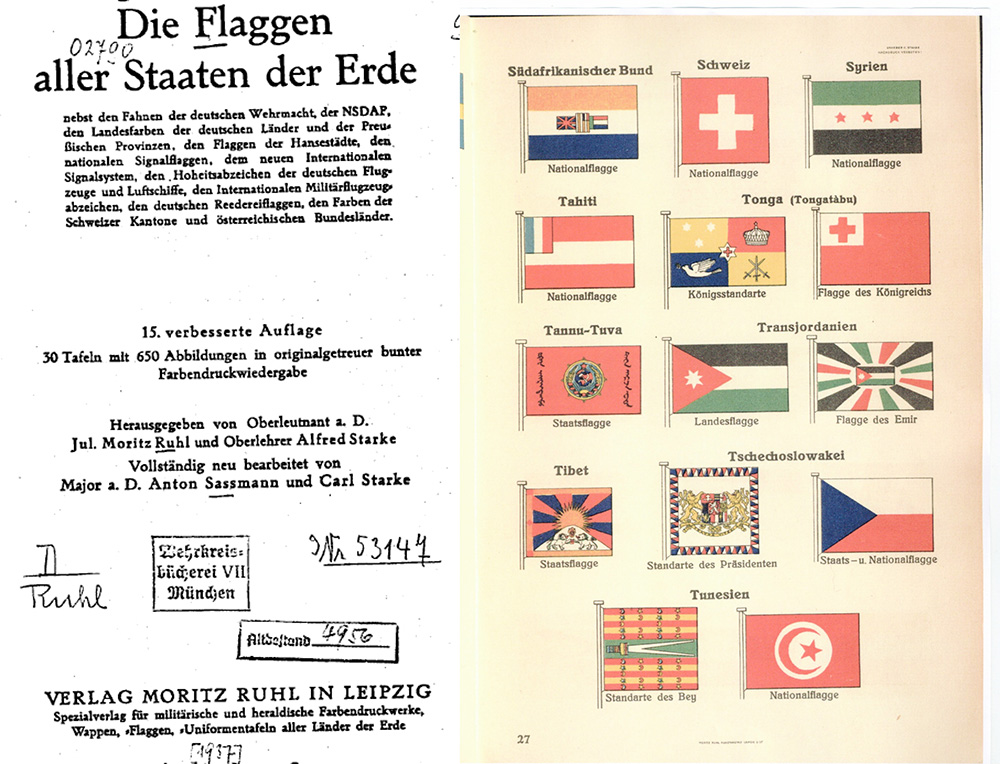

Ms. Engelhardt also kindly sent me copies of pages from a German publication of 1937, Die Flaggen aller Staaten der Erde, where the Tibetan flag was displayed alongside flags of other nations.[3]

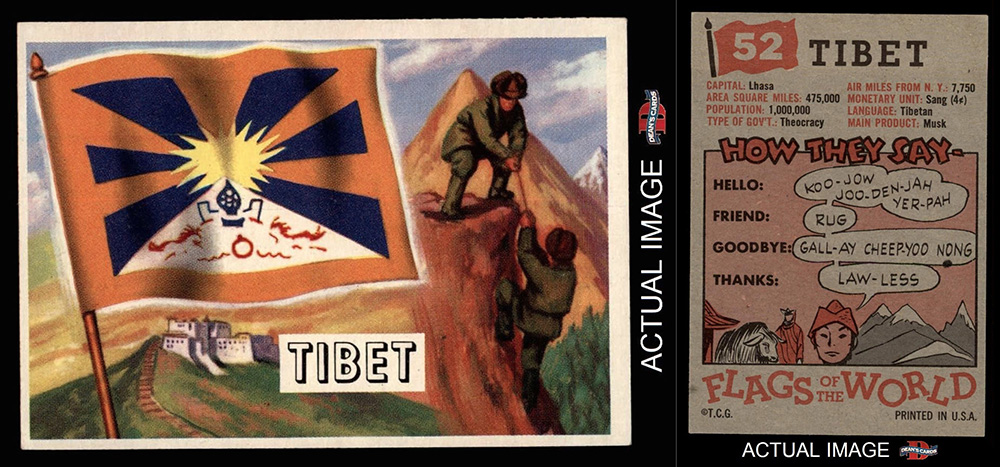

Veteran Tibet activist Dr. Jan Anderson sent me a copy of a German cigarette card issued in 1933, which carried an image of the flag of Tibet with the gold border (card No: 222), and carried the caption “Tibet Nationalflagge”. The card was issued by Bulgaria Cigarette Factory, Dresden, and was in a collection of flags of the nations of the world.

Starting from the early 20th century, manufacturers of cigarettes, bubble-gum, candy etc., began to issue collectable cards of famous monuments, animals, sports heroes, movie stars and as mentioned “Flags of the World” with their products. It came as a pleasant surprise to me to discover that a number of such trading cards in the UK, Germany, Holland, the United States carried reproductions of the Tibetan national flag and, often, some basic information on Tibet, on the reverse. One such card was possibly issued as early as 1919 or 1920.

I am not going into further details on Tibet related trading-cards. Nick Gulotta, A Tibet activist and collector of such memorabilia, has been working on a major study of Tibetan Flag trading cards, which will be released soon. I am sure it will be entertaining and informative. I will let readers know about it the moment it is on line.

Some of you may feel it is a waste of time studying such trivial aspects of western juvenile culture – even if it relates to Tibet. But for me these objects clearly reveal that in the first half of the 20th century there was a general (if cursory) awareness in much of the world of Tibet as an independent, albeit mysterious, nation, with its own unique national flag. It is reassuring to know that all you need are a few cigarette and bubble-gum cards to demolish the assertion of certain hostile academics that Tibetan exiles fabricated the trappings of their “bogus” national identity after 1959.

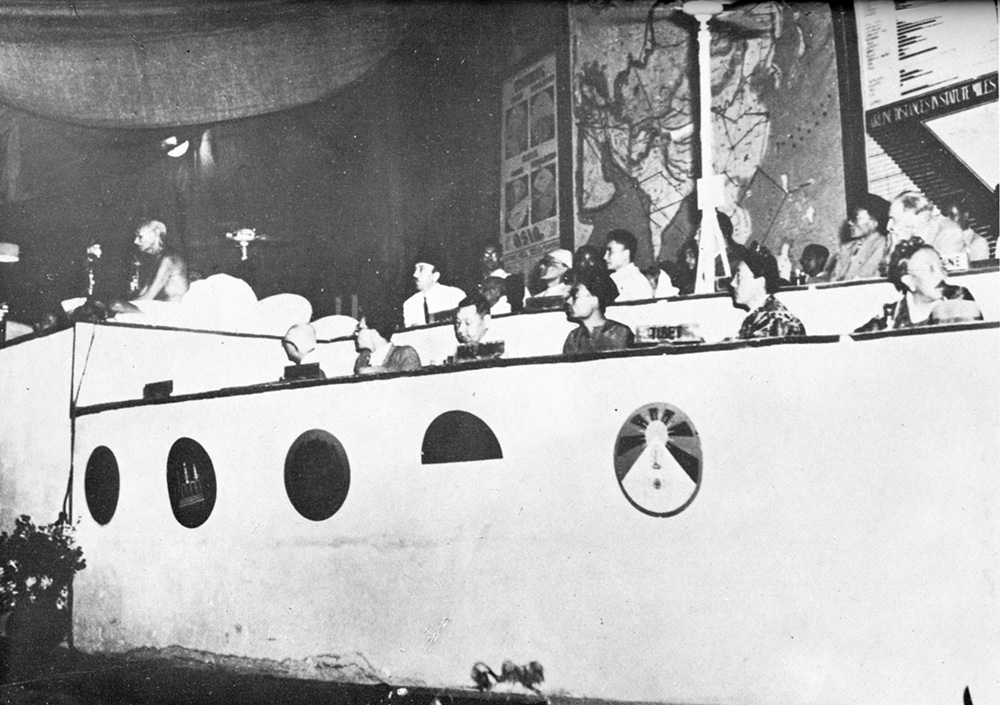

I want to conclude this particular review with an account of the first official international debut of the Tibetan National Flag at the Asian Relations Conference at New Delhi on 23rd March 1947. This Conference, organized by Pandit Nehru and the Government of India, brought together many leaders of the independence movements in Asia and represented a first attempt to assert Asian unity. The Tibetan flag was displayed alongside the flags of other Asian nations, and a circular flag emblem placed before the Tibetan delegation on the podium.

But PRC propagandist, Tom Grunfeld, has argued, somewhat nit-pickingly, that the conference was not government-sponsored, and so Tibet’s and the Tibetan flag’s presence had “no diplomatic significance”[4]. Grunfeld’s reasoning is almost certainly based on the fact that the Indian government was then a provisional one, as independence would only come four month later on 15th August 1947. But this argument is misleading in the extreme. The British Government of India recognized the Conference as an official one and its representative in Lhasa, Hugh Richardson, personally handed over the invitation to the Tibetan Government, and strongly advised it to attend. Furthermore, to this day, the Government of India regards the Asian Relations Conference as an official Indian one. So whatever the official status of the Tibetan flag at present, it unquestionably had official recognition and “diplomatic significance” in Delhi on March 1947.

And we must ask this question. If it didn’t have “diplomatic significance” why did the Republic of China protest the display of the Tibetan flag on the podium, and also the large map of Asia at the back (which presumably showed Tibet as a separate country)? One American academic, probably using Chinese sources, has written [5] that the flag and the map were subsequently removed, but a Tibetan delegate who actually attended the conference has written in his biography [6] that nothing of the sort happened. The weight of factual evidence is on the side of Tibetan delegate, Rimshi Sampho Tenzin Thondup (son of a delegation leader, Teiji Sampho) as he is the only conference participant (Tibetan, Indian or Chinese) who has written on this issue. Furthermore the only photograph available of the conference clearly shows that at a most important session where Mahatma Gandhi addressed the full conference, the large map of Asia is still at the back, the Tibetan flag is still on the podium, and two Tibetan delegates are seated nicely behind it.

Notes

[1] Grosvenor, Gilbert and William J. Showalter, “Flags of the World”. The National Geographic Magazine: September, 1934 – Vol. LXVI – No. 3. Washington, D.C.” National Geographic Society, 1934. Kindly brought to the compiler’s attention by the late Tendar la.

[2] Admiralty, By Authority. Drawings of the Flags of All Nations. His Majesty’s Stationary Office. London. 1930. Information & image courtesy of Isrun Engelhardt

[3] Die Flaggen aller Staaten der Erde, Verlag Moritz Ruhl, Leipzig, 1937. Information & image courtesy of Isrun Engelhardt

[4] A. Tom Grunfeld, The Making of Modern Tibet. 1996.

[5] John W.Garver, Protracted Contest: Sino-Indian Rivalry in the Twentieth Century. University of Washington Press. 2001.

[6] Sampho Tenzin Thondup, (In Tibetan) metse balap trukpo (The Violent Waves of My Life), self-published, Dehradun, 1987

Tibetans needs to wake up and stop this day dreaming middle way non-struggle path!!!

isn’t the time that has been passed is enough? what you are waiting?

As usual great article! Thank you

TCL

Thanks for adding substantive information to our history of Tibetan National Flag. Great Job. Bod-rGyal-Lo.

Well information, thanks