In a recent piece (Running Dog Propagandists) I made a reference to an old review essay of mine of Tom Grunfeld’s Making of Modern Tibet. A couple of readers emailed in to say they could not locate the piece. I discovered I had not posted it on Phayul.com and that it was impossible to find on WTN or Tibetwrites.org. So I am reissuing it here to round off our “running dog” discussion on this blog . I have taken the opportunity to correct a few typos and also nail the source of the opening quotation I had earlier cited, somewhat incompletely, from memory.

ACME OF OBSCENITY

Tom Grunfeld and The Making of Modern Tibet

In his Epistulae (Letters) the younger Pliny mentions that his uncle the natural historian and philosopher, Pliny the Elder, used to say that “no book was so bad but some good might be got out of it.” Well, that was back in ancient Rome. Whether such an outlook could embrace contemporary hate literature and racist tracts produced by white-supremacist groups, Islamic fundamentalists or the propaganda material generated by the Ministry of Truth in Beijing, is, of course, quite another matter. Nonetheless, even in that extremity it might be possible to argue that such publications at least serve to inform us of a point of view – no matter how distorted, hateful or ugly – of certain groups of people in this world, thus fulfilling a function of sorts.

In the hate/propaganda genre there is a sub-class of publications, which through their authors’ skill in providing a superficial gloss of scholarship or professed objectivity to their work, render them capable of great mischief. Chief among these is, without doubt, The Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion, a document put together by the Okhrana, the tsarist secret police, purporting to be the report of a series of twenty-four meetings held by Jewish leaders and Freemasons in Basle, Switzerland in 1897, to make plans to take over the world. It was translated into practically every European language, also Arabic and Urdu, and its effect has been poisonous in the extreme.

Mother India (1927), by American journalist Katherine Mayo, is a work that purports to be one of genuine concern for the welfare of the Indian people. It is a mishmash of the usual simplistic indictments of Indian society: the caste system, child marriage and so on, topped off with such spurious and outrageous charges as that Indian mothers regularly masturbated their sons “to make them more manly.” It is essentially a racist tract serving to confirm long-held prejudices of white people against Indians, and, in essence, making out the case that Indians were an exhausted race of sexual degenerates morally unfit to rule themselves. This message was grasped eagerly in Britain where Mother India received enthusiastic press reviews. The book’s success in the USA did considerable damage to the Indian cause there, which till then had been gaining in support and sympathy.

Tom Grunfeld’s, The Making of Modern Tibet (Zed Books, 1987) is a work that is more in line with Mayo’s book than with The Protocols. Grunfeld doesn’t exactly accuse Tibetan mothers of masturbating their sons, but he does claim that “babies were not washed as they emerged from the womb but sometimes licked by the mother” – like animals. He offers neither source nor citation for this amazing fabrication. He goes on to specify that Tibetan were cruel, dirty, ignorant, syphilitic (90% of the population suffering from venereal diseases according to TG) sexual degenerates who were observed making love on rooftops in full public view. Why make such outrageous accusations, you may ask? What purpose does such ridiculous abuse serve? But these are not random insults Grunfeld is hurling, but essential components of his greater design – to expose Tibetans as barbaric, subhuman, even bestial, thereby justifying Chinese rule in Tibet as necessary and civilizing. It is particularly galling for any Tibetan even to have to deny such charges, coming from a propagandist for a country where till fairly recently, ritual cannibalism of the most gruesome kind was practiced to honour Chairman Mao (Scarlet Memorial: Tales of Cannibalism in Modern China, Zheng Yi, Westview Press, 1996)

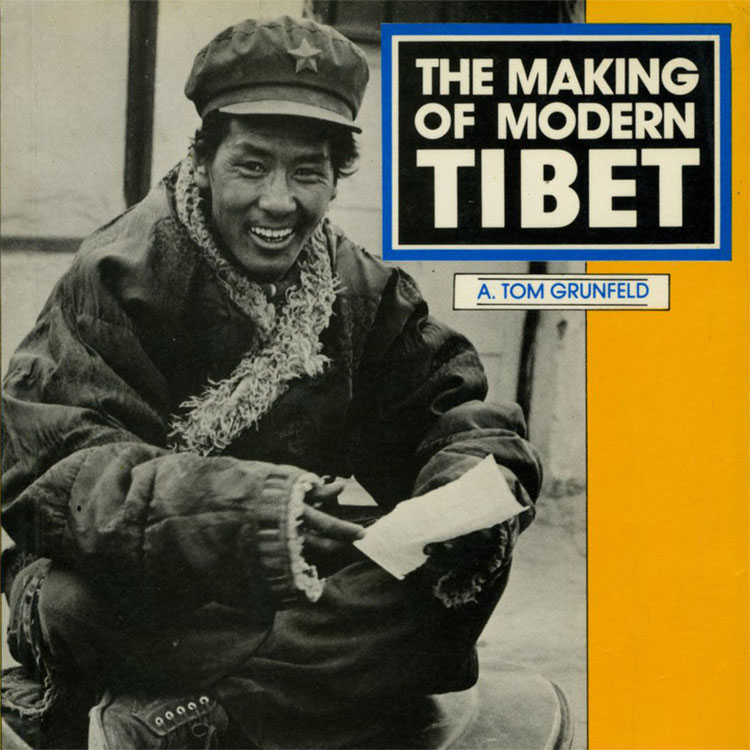

The first clue I got of Grunfeld’s closet racism was on the cover of his book. It shows a Tibetan man sitting cross-legged on what appears to be an oversized garbage can. He is wearing an old sheepskin robe incongruously topped off with a large Mao cap adorned with a star in the front. He also has a wide grin plastered on his face. It reminded me of those racist postcards once said to be sold in stores in the American South, the kind where a happy black man is sitting on a barrel with a big slice of watermelon (or a banjo) in his hands and a wide grin on his face. Another image that came to mind was that of the stereotypical cartoon depiction of an African tribal chief: a fat black man with lips like a jelly doughnut, wearing a grass skirt, a bone ornament inserted through his nose and a shiny top hat perched rakishly on his head.

Grunfeld’s other efforts to establish that pre-invasion Tibet was a corrupt, cruel and degenerate country relies heavily on a very discredited device – selective quotations wrenched from context. For instance, though Grunfeld has to admit that Chinese propaganda about Tibetans practicing human sacrifices is without evidence, he goes on to write that “The most convincing clue we have comes from Sir Charles Bell. Bell wrote that he once visited a spot on the Tibet-Bhutan border where he saw a stupa called Bang-kar Bi-tse cho ten that contained the bodies of an eight year old boy and girl ‘who had been slain for the purpose’ of some religious ritual.”

What Grunfeld omits to tell us is that Bell is talking about events of the distant past, as he clearly mentions that the stupa had been built “many years ago.” Furthermore it is evident that Bell intended the story as folklore, as an old tale that someone else had told him, and not as an eyewitness account. We can confidently assume that Bell did not tear apart the stupa (in the manner of the Chinese Communists) to check for the corpses. Bell also immediately follows up the sentence about the two bodies with this line: “Scenting the corpses and blood a demon took possession of the chö-ten”, bearing out the “ghostly legend” nature of his account. (Tibet Past and Present, pg.80). Charles Bell also writes that the area in question (Tromo) had been a stronghold of the old pre-Buddhist faith, Bon. This, in all probability, makes the stupa in question an old Bon one, and not the usual Buddhist stupa that is the familiar feature of the Tibetan landscape. Furthermore the charges against the Bon religion of human sacrifices and black magic is to a very large extent based on Buddhist clerical misrepresentations about a once successfully competing belief – resembling Christian propaganda about pre-Christian “pagan” religions. No scientifically acceptable evidence has, to this day, been unearthed (even by Chinese academics) that savage rituals and practices of the kind that prevailed in pre-Columbian Central and South America ever existed in Tibet, even in remote antiquity.

If an American tourist at Stonehenge, on being told by locals that virgins were once sacrificed there, used that bit of information to claim that human sacrifice was an accepted practice in modern Britain, he would probably be regarded as a candidate for the funny house. But such methodology is fairly standard throughout Grunfeld’s book.

Grunfeld also uses Bell’s statement that “slavery was not unknown in the Chumbi valley” to imply that slavery was a standard institution throughout Tibet. Once again Grunfeld does not include Bell’s subsequent remarks that the institution was then on the wane and that “only a dozen or two (slaves) remained”; and that “the slavery in the Chumbi valley was of a very mild type.” (Tibet Past and Present, pg.79). Grunfeld further completely fails to mention that Bell made these observations in 1905 when, as assistant to Claude White, he was posted in the Chumbi valley. This was at a time when slavery and bondage of a very cruel, inhuman and completely legal kind was universal throughout China, and also prevalent in large parts of the British Empire in the legalized form of “indentured labour.” If we adopt Grunfeld’s cavalier style of stretching events of 1905 to fit anywhere before 1959 (when the Chinese Communists took full control of Tibet, and which is Grunfeld’s cut-off date for “Tibet As It Used To Be”) we could probably overlook the fact that slavery ended in the United States in 1863 and compare it to what was going on in Tibet in 1905. We should also bear in mind that the “very mild kind of slavery” of “a dozen or two people” can hardly stand comparison with the slavery practiced in the USA where, for example, in South Carolina 64% of the population were slaves, and where every manner of torture and cruelty were inflicted on them, and where well into modern times such people could be “lynched” for the most trivial of reasons.

Even the few instances of “mild” slavery that Charles Bell reported in 1905 almost certainly disappeared in the following years, for later accounts of Western travelers and even long term European residents of Tibet as Heinrich Harrer, Peter Aufschnaiter, Hugh Richardson and David MacDonald make no mention of any such practice. What ensured its disappearance is almost certainly the Great 13th Dalai Lama’s reform and modernization programmes, which despite some setbacks in such areas as modern education, managed to take unprecedented and far-reaching steps to protect the rights of the most humble Tibetan peasant and nomad against exploitation and official corruption.

Perhaps it should be mentioned here that in 1913 the 13th Dalai Lama officially banned capital punishment and other forms of “cruel and unusual” punishments; possibly making Tibet one of the first countries in the world to do so. Switzerland abolished capital punishment in 1937; Britain in 1965 and France guillotined its last criminal in 1981. In the United States, especially Texas, even being underage or mentally retarded is no guarantee of not being sent to the “chair,” or whatever is on offer. In China they are going at it as if there were no tomorrow. An “execution frenzy” was how an Amnesty International press release of July 6, 2001, termed it. The press release went on to state that “More people were executed in China in the last three months than in the rest of the world for the last three years.” 1781 executions and 2960 death sentences passed in three months. Yet, according to Amnesty these statistics are likely to be far below the actual number.

The 13th Dalai Lama even turned down (in 1896) his cabinet’s recommendation to execute his former regent and accomplices who had conspired to assassinate him. There is a possibility that the main conspirator, the Nyaktrul sorcerer, was secretly murdered in his cell by an overzealous official, but there is no evidence of any higher official involvement. Even the few instances in which this law was breached serves to demonstrate the fullness of Tibetan commitment to the Great 13th’s ideals. In 1924 when a soldier died under punishment, Tsarong, the Commander in Chief of the Tibetan army, a man who had personally saved the Dalai Lama’s life, was permanently relieved of his duties. Not only is there no record of executions after 1913, but the one recorded case of a “cruel and unusual” punishment serves to demonstrate how deeply the law had taken root in Tibetan life. Some years after the death of the 13th Dalai Lama, the official, Lungshar, attempted a coup d’état. On its failure many in the government wanted him executed but the old law stood in their way. So Lungshar was sentenced to the lesser punishment of having his eyes removed. The operation was badly botched. Such punishments had for so long fallen into desuetude that, according to Melvin Goldstein, the class of people who in the past had carried out executions and such punishments “told the government that they were only able to do it because their parents had told them how it was done.”

But, to get back to the issue of slavery, let us put matters in perspective. Surely Grunfeld is aware of the Laogai camps in China where millions of wretched inmates, are, as we speak, toiling in unimaginably horrendous conditions, at what can only be described as slave labour. But even in “normal” Chinese society today slavery is not only prevalent but increasing, according to a report in the Far Eastern Economic Review entitled “Toil and Trouble: Slavery is on the rise in China as number of poor migrants increases. Beijing appears unwilling and unable to prevent it”, by Bruce Gilley, Aug 16, 2001. Professor Hu Shudong of the China Economic Research Centre at Beijing University makes the case that slavery is widespread in present day China and prevalent in many different industries and occupations.

When making his very selective quotations of Sir Charles Bell, Grunfeld takes care to establish Bell’s bona fides as a British colonial official and “a renowned Tibet scholar”. But then Grunfeld completely fails to inform his readers that Charles Bell’s main contention in all his books is that Tibet was an independent nation – culturally and historically distinct from China. While pointing out that Tibetans and Chinese were racially distinct, Bell took pains to point out a number of singular differences:

“… the two races differ strongly in many qualities which have their roots deep down in the characters of the two nations …Firstly, the Tibetans are deeply religious… The Tibetan government is truthful. It can be slow, obstinate and secretive in dealing with foreigners, but it has a strong regard for truth. But the Chinese authorities from time to time made statements which were deliberately untrue…The Chinese are far more cruel than the Tibetans are. When they tried to conquer areas in Tibet, they used to put to death what prisoners of war they captured, although the only offence of these was fighting in defence of their homeland. The Tibetans, when they captured Chinese prisoners of war, used simply to send them back to China. The Chinese treat the granting of a favour merely as a step towards asking for another…The Tibetans do not treat favours in this way. They have a national memory of things for which they are grateful … Many other examples of the differences dividing these two nations could be given … For instance, the status of women in Tibet is higher than China; the kinder treatment of animals; and the more orderly government.” (Portrait of the Dalai Lama, pg. 353 – 354.)

Grunfeld’s wrenching quotations out of context even extends to a few quotes from my book, Horseman in the Snow. To discredit Bell’s and others’ observations that women in Tibet were treated on a basis more equal to that of men than in neighboring China, Grunfeld triumphantly pulls out this line from my book, “A man’s wealth was, first and foremost, measured through the number of sons he had.” Once again Grunfeld fails to include the subsequent sentences which read: “ It was a matter of survival. Strong hardy sons were needed in every family to work and to fight bandits and settle feuds.” And why was it so? Why was this area so violent and lawless? Because it was under Chinese administration. In that part of Tibet administered by the Dalai Lama’s government “where law and order prevailed” as my informant emphatically states in the same book, the social status of women was higher, and certainly in advance of contemporary China with its foot-binding and child concubinage, and even present-day China with it’s mind-numbing and sickening statistics on female infanticide.

Grunfeld uses a similar trick in order to allege that descriptions of the typical Tibetan diet of tsampa, butter tea, meat and vegetables were exaggerated and that “a survey made in 1940 in eastern Tibet came to a somewhat different conclusion. It found that 38 percent of the households never got any tea but either collected herbs that grew wild or drank ‘white tea’, boiled water. It found that 51 percent could not afford to use butter, and that 75 percent of the households were forced at times to resort to eating grass cooked with cow bones and mixed with oat or pea flower.” Once again Grunfeld neglects to inform us that the survey was made in a long-held and Chinese administered area of Tibet, where the rapacity of Chinese officials ensured not just the poverty of the population but often its starvation as well. Grunfeld’s notes at the end of his book exposes his deception. The source is Frontier Land Systems in Southwestern China, by Chen Han-seng, 1949.

In 1916 an American missionary, with experience in Chinese administered Eastern Tibet wrote: “There is no method of torture known that is not practised in here on these Tibetans, slicing, boiling, tearing asunder and all …To sum up what China is doing here in eastern Tibet, the main things are collecting taxes robbing, oppressing, confiscating and allowing her representatives to burn and loot and steal.”

This observation is mentioned in Travels of a Consular Officer in Eastern Tibet, by Eric Teichman of the British Consular Service in China who, on the request of the Chinese government traveled extensively through Eastern Tibet in 1918, to conclude an armistice between warring Tibetan and Chinese forces. In his book he observes that the areas of Eastern Tibet administered by the Tibetan government were peaceful, orderly, well administered and contrasted dramatically with the lawlessness, poverty and misrule in Chinese administered areas. Teichman also cites similar observations by other European travelers who had traveled to both areas.

Grunfeld’s chapter on early Tibetan history is absolutely disingenuous. While relating Songtsen Gampo’s marriage to the Chinese princess as an “enlightened” move on the Tibetan’s Emperor’s part, concurring with standard Chinese propaganda that Tibetans were eagerly seeking “superior” Chinese culture, he is completely silent on the fact that the princess was in fact a tribute, a prize wrested from the Chinese emperor’s hand after the Tibetans had soundly defeated a major Chinese army in battle.

Grunfeld mentions without qualification (and again without sources or citations) that the Chinese princess “is credited with having introduced into Tibet the use of butter, tea, cheese, barley, beer, medical knowledge, and astrology. If butter, cheese, and barley, which are staple food items of the Tibetans, did not exist in Tibet before the arrival of the Chinese princess, what does Grunfeld suppose Tibetans ate? Grass perhaps, which would, in a sense, support Grunfeld’s other contention that Tibetan women licked their newborn babies clean, thus confirming the subhuman, perhaps bovine, nature of the Tibetan people.

Far from introducing such products to Tibet, the Chinese traditionally never ate cheese, butter and milk, and well into modern times regarded dairy products as somewhat disgusting. It is amazing that a person who nowadays refers to himself as “a historian on China”, should lack such basic knowledge about traditional Chinese diet.

And this is perhaps where mention should be made of the fact that Grunfeld most probably does not read or even speak Chinese, since in his work he provides no primary Chinese sources. Furthermore, it is more than obvious that Grunfeld does not speak or read even basic Tibetan. Not a single Tibetan source is cited in his book. In fact his “history” relies on often outdated secondary literature, and does not even utilize the significant body of scientific and scholarly articles and monographs that have appeared (in English and other European languages) over the last twenty-five years or so.

Though problematic, linguistic inability might not, under certain circumstances, prove so absolutely crippling in conducting research on Tibetan history. Alastair Lamb’s Tibet, China & India 1914-1950, derived largely from official British archival sources, is a significant contribution to our knowledge of modern Tibet history. Also use of translators, long term contact with Tibetan scholars and close association with the Tibetan community could also possibly compensate in part for lack of language skills, as Warren Smith’s Tibetan Nation demonstrates. Grunfeld has no dealings whatsoever either with Tibetans-in-exile or those inside Tibet, though he has made a couple of visits to Tibet, one just recently. He does occasionally attend seminars and lectures on Tibet in New York City, where he sits at the rear of the hall with a newspaper or journal held up before his face. During breaks he has been known to pour out, to anyone willing to listen, woeful accounts of Tibetan mistrust and hostility towards him.

Grunfeld is patently dishonest in not owning up to his ignorance of the Tibetan and Chinese languages. He skirts the issue in the introduction to his book by claiming that he was aware that he had not drawn on Tibetan and Chinese sources, but that getting his book published took priority. He also has the shameless effrontery of justifying this with a quote from Hugh Trevor-Roper: “All researchers reach a point of diminishing returns where to continue without publishing only postpones the inevitable.” On another occasion he fobs off his ignorance of Tibetan and Chinese with this blatantly false declaration: “Chinese, Tibetan and Nepali sources are not very plentiful, on the whole, and not readily accessible even if one has the necessary language skills.” (Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars, IX.1, 1977: 59) Granted, Nepali sources may not be plentiful, but at the same time they are not as vital as Chinese and certainly Tibetan sources are in studying Tibetan history. And Tibetan sources are undeniably plentiful. They are also completely accessible to Grunfeld in New York City. Thanks to a US Library of Congress program, under the PL480 program, from the mid-sixties onwards, copies of many thousands of volumes of basic, primary materials for historical research on Tibet were made freely available at such institutes as Columbia University or the New York Public Library – to anyone with “the necessary language skills ” to read them.

Grunfeld even seems to lack the smattering of basic Tibetan that tourists to Tibet or hippies in Dharamsala manage to pick up in a few days. For instance in the introduction to his book he translates the Tibetan name for Tibet “Bod (or ‘P’oyul)” as “the land of snows” which is laughably pathetic. “Bod” absolutely does not mean “land of snows”. Tibetans do sometimes refer to their country as “gangchen jong” or “land of the great snows” in the same way as an Irishman might refer to his country as the Emerald Isle. Grunfeld’s book is so rife with such elementary mistakes that I think it is pointless to go on pointing them all out. The task could be more suitably performed at a Tibetan school perhaps, where children could compete with each other to spot all the many howlers.

Such being the case, I would be justified in asking Grunfeld the same question that Nirad Choudhuri (the great Bengali polymath and writer) asked of Katherine Mayo: why she, “who on the face of it, had neither the qualification nor any business to write on India”, undertook her project. Mayo’s book was suspected by many Indians of being inspired, if not commissioned by British officials in India. Even Gandhi was goaded to write, “We in India are accustomed to interested publication patronized – ‘patronized’ is accepted as an elegant synonym for ‘subsidized’ – by the Government… I hope Miss Mayo will not take offence if she comes under the shadow of such suspicion.”

In 1971, Manoranjan Jha, came out with a study Katherine Mayo and India, which provided extensive documentary evidence to show that British authorities in India from the highest to the lowest ranks had indeed not only actively helped Mayo but had supplied much of the scandalous details. According to Mayo’s papers now at Yale University, John Coatman, Director of Public Information to the Government of India, had provided her with such salacious tidbits as that Indian men often practised sodomy on their own sons.

Like Mayo, Grunfeld claims that his work is honest, objective and motivated by genuine concern; and like Mayo, Grunfeld takes up a posture of martyrdom when attacked by critics. But the fact of the matter is that like Mayo, Grunfeld is a hypocrite and racist, and also the agent (probably less unwitting than Mayo) of a tyrannical imperial power.

Grunfeld was a member of the “US China People’s Friendship Society” which Simon Leys has pointed out has nothing so much to do with friendship among peoples, as with serving the will of the Chinese Communist Party. He was also on the staff of New China, the propaganda vehicle of the Society, and was also a contributor. In 1975, before the Cultural Revolution had ended, when everything in Tibet seemed reduced to rubble and misery by this campaign’s violence and madness, Grunfeld wrote an article, “Tibet: Myth and Realities,” for New China. In it he unreservedly declared that extensive modern education, widespread healthcare, scientific agriculture, industry, commerce, and even indigenous cultural life were flourishing in Tibet. Even Chinese officialdom later admitted that Tibet had suffered terribly and conditions had gotten far worse that what was supposed to have prevailed in pre-1950 Tibet.

Grunfeld was also a member of the Committee of Concerned Asian Scholars, a now discredited organization of left-wing Mao-worshipping Western academics who subscribed unquestioningly to the belief that Mao and the Communist Party of China had not only solved the problems of China but those of humankind as well; and that Communist China should be regarded as a model not just for developing nations, but also the United States. When, at a meeting with Zhou Enlai a group of Concerned Asian Scholars sought to extol China’s many achievements, the premier, irritated by their infatuation with the Cultural Revolution, cut them short by saying that much remained to be done. The deputy foreign-minister Chao Guanhua, complained about such adulation from the West with this objection “They used to write that everything in China was wrong. Now they write that everything in China is right.” As Steven Mosher in China Mispercieved exclaimed in amazement: “This must surely rank as one of the wonders of the global village: Beijing’s master image-makers giving lessons in balance and objectivity to American journalists.”

But is Grunfeld connected more directly to the Chinese government or the Communist party – in some covert manner, perhaps? A revelation by a longtime friend of his indicates that he probably is. In his book China Live: Two Decades in the Heart of the Dragon, CNN Hongkong Bureau Chief, Mike Chinoy writes that following the 1987 demonstrations in Lhasa, CNN‘s attempts to get permission to visit the Tibetan capital were constantly rejected by Chinese authorities. But in the summer of 1988 “Tibetan historian Tom Grunfeld, a longtime friend and fellow CCAS (Committee of Concerned Asian Scholars) activist from the 1970’s with good access to senior Chinese officials responsible for the territory, was allowed to visit Lhasa, where he lobbied on our behalf. Two months later, we were thrilled to receive a telex from the Lhasa waiban inviting CNN to Tibet”. There are only so many ways one acquires such clout, such impressive guanxi, in the PRC. One thing we can be sure is that Grunfeld doesn’t have a spare million dollars to invest in China.

Earlier on, I dealt at such length on Grunfeld’s equivocations on early Tibetan history and old Tibetan society that I now feel obliged to emphasize to the reader that the bulk of Grunfeld’s book deals with Tibet after the Chinese Communist invasion. It is also here, in a presentation comparable only to Houdini’s amazing trick of making a live elephant disappear on stage, Grunfeld performs a mind-boggling tour de force. He manages to write his entire account of this period without once referring to any famine either in Tibet or China, and does not even make a remote allusion to the “great famine”. A famine which is now generally acknowledged to be the greatest in human history, where 30 to 60 million people died and where starving people boiled and ate their own children. Furthermore this famine was not an act of nature, but occurred as result of Mao’s megalomaniac programs and the Party’s complete indifference to human life and suffering. To Grunfeld, all this never happened. Instead he regales us with heady accounts of steady progress and reforms from the first instance the Chinese took power in Tibet. A summary of these amazing accomplishments is presented in his article in New China, “… a decade earlier mutual aid teams were formed, then agricultural cooperatives, and finally, in 1965-66, people’s communes. Mechanization has begun and experimental agricultural stations have developed more resilient, higher-yield grains as well as strains of tobacco, tea, sugar beets, and a dozen vegetables, which can grow readily in the climate of the ‘Roof of the World’. Innovations such as insecticides, chemical fertilizers, irrigation, and veterinary medicine have been introduced into a land that hardly even know of their existence … In short the lot of the Tibetan people has improved immeasurably.”

Another black hole in Grunfeld’s account is the imprisoning of hundreds of thousands of Tibetans in Forced Labour Camps, and also the mass killing of Tibetans by the Chinese. Grunfeld is absolutely silent on this. China’s leading official Tibetan figure, the Panchen Lama, in his address to the Tibet Autonomous Region Standing Committee Meeting of the National People’s Congress held in Beijing on 28 March 1987, clearly stated that in his native Amdo (Qinghai) “there were between three to four thousand villages and towns, each having between three to four thousand families with four to five thousand people. From each town and village, about 800 to 1,000 people were imprisoned. Out of this, at least 300 to 400 people of them died in prison”. Nearly half the prison population.”

At the same meeting the Panchen Lama also provided specific instances of mass killings in his area. This is what he said: “If there was a film made on all the atrocities perpetrated in Qinghai province, it would shock the viewers. In Golok area, many people were killed and their dead bodies were rolled down the hill into a big ditch. The soldiers told the family members and relatives of the dead people that they should all celebrate since the rebels had been wiped out. They were even forced to dance on the dead bodies. Soon after, they were also massacred with machine guns. They were all buried there”.

Grunfeld’s silence on this issue makes his book the equivalent of a history of the American South with no mention of slavery, or a history of modern Germany without any reference to the Holocaust. Which brings up the question, is Grunfeld’s book comparable to the works of revisionist historians like David Irving who claim that the holocaust had never happened, that the gas chambers had never existed, but were invented for British propaganda purposes and then picked up by Jews to extort German and American finance for Israel? On serious reflection, I don’t think such a comparison can be made.

First of all David Irving is a real historian, whose works have been published by major publishers in Sweden, Germany and Macmillan in Britain, and not like Grunfeld’s “history” which was published by Zed Books in London, presumably some left-wing propaganda setup. Furthermore Irving is a fluent linguist and speaks and writes German like a native. In fact his knowledge of German language, history and culture is so exceptional that he was able to expose the phoney “Hitler Diaries” that the German magazine Stern had purchased and published (excerpts) in 1983 and which had been publicly endorsed not only by a number of German experts but even by the historian, Hugh Trevor Roper, whom Grunfeld quotes to prop up one of his numerous falsehoods.

Also David Irving is no hypocrite or the cat’s paw of a brutal dictatorial regime as Grunfeld is. No matter how distasteful and abhorrent his views, David Irving is at least open and straightforward about them. He does not pretend that he has nothing to do with neo-nazi groups, and in fact he openly lectures at large gatherings in Germany where he is greeted with enthusiastic “Seig Heil’s.” More than anything he does not pretend to be the disinterested friend of the Jews. And to credit the man, Irving does not retail mediaeval anti-Semitic vilification, like the kind that Jews poisoned wells and performed secret rituals with the blood of murdered Christian babies. Nor does he repeat racist slurs about Jews being dirty, miserly, treacherous or sub-human. All of which Grunfeld enthusiastically does, in the Tibetan context.

But I find myself unable to go on any further. I must come up for air – pull my head out of the open sewer that is Tom Grunfeld’s The Making of Modern Tibet. If the printed word could physically emit a stink, then this book would reek not only of dung and putrefaction but the charnel house as well. All the usual words of condemnation: scurrilous, disgusting, abominable, are inadequate to censure the man and his work. Once again, as I have done many times in the past, I am obliged to touch on the experiences of Lu Xun for an adequate concluding description of this deeply disturbing hate-tract and its perverted author. And modern China’s preeminent humanist and writer, a man with a lifetime experience of skewering tyrants and their toadies on his mobi, his writing brush, does not disappoint. With his withering dismissal of the writings of Zhang Shizhao – one of the more unredeemably disgusting intellectual whores in the world of Chinese letters – as the “acme of obscenity”, Lu Xun allows me conclude this piece.

August 28, 2001

It’s just like you say. To judge from the book cover in combination with the book title, modernity* means wearing a traditional chuba (?), a mao hat, army boots, and sitting on the lid on a garbage can (or are we seeing something that isn’t there?). I’m getting the message that, since only the mao cap is especially modern, the one hero responsible for all this wonderful modernity must be Mao and his Great Leap. Can’t wait for Tom G. to send in his talkback. We’ll have him for lunch.

*I don’t mean to imply that I know what modernity is. I mainly wonder if there’s anything to it beyond the electronics. We have the people who say, Well, Tibetans are getting modern, how wonderful and the people who say, Well, Tibetans are getting modern, how sad. Personally I hope people will be as modern as they want to be. But preserve the main human values in any case. Like happiness and the pursuit of same for starters (even if, and especially if, life *is* pervaded through and through with suffering).

All this reminds me that the only way mass killings can be proved would be to exhume the remains to examine the causes of death. I have heard from elders of at least one place.I wont mention it here

though. Perhaps in the near future we will have the

chance to expose these heinous chinese crimes. I have heard from the older generation of new-comers or visitors from Tibet as well as personal stories which my father heard of absolutely sickening torture methods which seem almost impossible to believe. However there must be a kern of truth to all this otherwise the entire tibetan nation must be a race of liars which the Chinese seem to imply. All this in the name of liberation and development. Read invasion and colonise:note I dont use the word settle. Colonise is better because it serves to remind those jingoistic Chinese nationalists that this is how we see them.

Chime Dorje la,

The most horrific nature of the insidious Chinese torture is the fact whole world will not acknowledge due to business inconveniences. Far prettier to wax on about religious freedom that is comfortable for the Christian right currently adorning the Oval Office of the “Free (apparently also free to lie and say Tibet is part of China) World.” One may well wonder at the humanity of foreign governments which intentionally conceal the extent of the Chinese brutality to protect their business interests. The human reaction and most deeply natural one would simply be to execute each Communist engaged to any extent in aforesaid brutal measures. Unfortunately there seems paucity of guns in Tibetan hands so some other tactics must prevailing…and if it is not possible to execute each and every last perpetrator (ah justice in this world so hard to come by) then let the world witness the gradual execution of Communism itself!

To humorously conclude the anecdote one may suggest that just as the China people invited Kundun unescorted to the opera so should leading Communist figures be invited unescorted to the more outlying districts in Kham. For tea and biscuits, no doubt!

Tashi Dele,

A great admirer of Tibetan culture and people, having lived and worked in Tibet and traveled throughout the greater Tibetan region, I find your blog and its crude argumentation an insult to the Tibetan people.

The Tibetan people are the first to acknowledge the shortcomings of the “old” system and attempts to whitewash the horrors of those “good old days” (no need to go into details) are silly.

Slavery, institutionalized rape in the monasteries, endemic use of torture by the various groups that controlled different, large and small regions of Tibet, in league with the established monastic orders, existed until long after the Chinese “invaded” Tibet (TAR??).

You are NOT ignorant of these things, but the many people who “suppoprt” the so-called “Tibetan” cause are, knowing nothing of Tibet , its people and history, most do not even know where Tibet is located!!

Ignorance is worse than poverty.

Om mani padme hum!

Murphy

Daniel, get lost. Your kind of inji trash is the kind that’s done so much harm to the Tibetan cause over the past 50 years. You make gross accusations with no evidence, taking Chinese racist rhetoric at face value. No one is trying to “white-wash the ‘good old days'” as you say, only to claim control over the future and make it a future people can be happy and proud of.

The number of people who have any idea what the “good old days” were like is actually nearly zero. If you meet a Tibetan who’s ashamed of them, it’s most likely because they’ve been fed Goldstein’s crap by institutions claiming to support the Tibetan cause. How many people have you spoken to who actually experienced the things you claim happened? I can answer that right away: none. If they actually existed, they are long since dead.

Now is not the time to retell the colonizer’s myths of how they civilized a “barbaric” people. Now is the time for people to fight for a just future. And the kind of crap you spew is antithetical to that goal.

You are not an admirer of the Tibetan people or culture, merely an admirer of your own self-deluded concept of what it is. So get lost. Forget Tibet exists. Go be a brick in somebody else’s wall.

Anything to comment about the latest words from T.G.?

http://www.thechinabeat.org/?p=1560

It seems the press (NPR at least) turned to him for political wisdom on His Holiness’ visit to Washington. Does this mean he’ll be the talking head punditji for Tibet-related events in the U.S.?

It has always been my belief that great writing such as this takes researching and talent.

It’s really obvious you have done your homework.

Wonderful job!