.

Rakra Thubten Choedhar (1925-2012), In Memorium.

The First National Conference of Tibetan Writers took place in Dharamshala in 1995 (March 15-17). Hosted by the Amnye Machen Institute (AMI), sixty-two writers and other delegates from India, Nepal, Switzerland, UK and USA took part in this first ever gathering of its kind in the Tibetan world. It was, without exaggeration, a historic moment for Tibetan belle-lettres, and even writers from inside Tibet, from as far away as Sining in Amdo, contacted us by phone to wish us well. PEN International sent us a message, as did the great Polish dissident writer, Czeslaw Milosz, winner of the 1980 Nobel Prize for Literature:

The First National Conference of Tibetan Writers took place in Dharamshala in 1995 (March 15-17). Hosted by the Amnye Machen Institute (AMI), sixty-two writers and other delegates from India, Nepal, Switzerland, UK and USA took part in this first ever gathering of its kind in the Tibetan world. It was, without exaggeration, a historic moment for Tibetan belle-lettres, and even writers from inside Tibet, from as far away as Sining in Amdo, contacted us by phone to wish us well. PEN International sent us a message, as did the great Polish dissident writer, Czeslaw Milosz, winner of the 1980 Nobel Prize for Literature:

Please receive my words of solidarity and sympathy. I lived a long time in exile and I understand your problems and your hopes. You have friends in many countries of the world, and you should be convinced that what you write in solitude and isolation will one day be known and remembered with gratitude.

The oldest and probably the best-known Tibetan writer to come to the conference was Rakra Rinpoche, he was seventy-one at the time. Most educated Tibetans probably knew him for his biography of the great Tibetan scholar and poet Gedun Chophel. Rakra’s biography was not only the first detailed, book-length biography of Gendun Chophel ever published, but was especially significant as Rakra had been a student of Gedun Chophel at Lhasa and had studied poetry (nyenga) and literature (tsom rig gyutsel) under him.

.

Rakra Rimpoche was well known in the exile Tibetan community as one of the most skilled practitioners of the art of classical Tibetan poetry (nyenga Tib., kavya Skt.). But even within this formal discipline Rimpoche’s work could be unorthodox and sometimes humorous. He wrote a didactic piece (Khe-drong-yak sum gyi lo gyue) where the eponymous yak complains to the great scholar Gedun Chophel of the ingratitude of the Tibetan people, and enumerates the many and invaluable ways that yaks had served Tibetans from the beginning of time, and how ungrateful Tibetans had repaid them by not only not depicting their majestic form on the national flag, but instead using the representation of a mythical creature, and one that resembled a Pekinese dog.

Rakra Rimpoche might be said to have served as an informal poet laureate for the exile community. He wrote verses of praise to the historian Wangchuk Deden Shakabpa, on the publication of his monumental Political History of Tibet, which the gratified historian reproduced in full, in the next edition of his book. An excerpt:

On this beautiful thousand-string lute that conveys the truth,

There are one thousand changing notes that are factual and correct.

You who have taken up and sung

This unblemished song of our history

Have awakened many beings from enduring sleep.

In 1969, on the 10th anniversary of the Tibetan National Uprising, Sheja Publication distributed in pamphlet form, Rimpoche’s long poem “The Message of the Khugda Bird”. This bird is regarded in Tibetan avian mythology as the herald or messenger of the cuckoo (khyu-yug), king of the birds.

In Rimpoche’s poem the messenger bird flies all the way from Tibet to India where he encounters an exile youth to whom he narrates the terrible sufferings of the Tibetan people under Chinese military occupation.

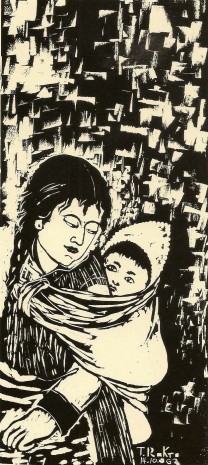

I think it was that same year Rimpoche made a beautiful woodcut of a mother and child fleeing war-torn Tibet. Entitled Flüchtlingen in German, many art prints and postcards of this woodcut were reproduced to raise funds for the Pestalozzi Children’s Village.

In 2008 when hundreds of activists in exile undertook a peace-march back to Tibet, Rakra Rimpoche wrote a “Prayer Song” for the occasion calling on all the old gods and goddesses of Tibet to protect the marchers and guide them across the high mountain passes:

All thoughts of turning back have been abandoned on the road behind

Our feet compel us to march forward to Tibet –

To Lhasa, abode of the gods, gathering place of our people,

The capital city of all Tibetans, more precious than life.Friends, do not offer the welcome chang (beer) right now,

There will be time enough for us to meet, drink and rejoice.

Let us first greet the Buddha Jowo at the Jokang Temple.

Rakra also wrote vers d’occasion for auspicious periods in the Tibetan calendar as the Losar, the Tibetan New Year. He regularly sent Losar greetings in original verse to the Dalai Lama and his two tutors, Ling Rimpoche and Trijang Rimpoche. A Tibetan literateur told me that if His Holiness’s private secretariat had bothered to save the verses they might be compiled to make a small book.

This somewhat atypical Tibetan lama was born in 1925 (Fire Ox Year) to Gyurme Gyatso Tethong, then Governor of Derge (Derge chikyap) and Dolma Tsering nee Rong Dikyiling (d/o Dikyiling Sawang Tsering Rabten). The boy was named Rigzin Namgyal by Khenchen Ngawang Samten Lodroe (1868-1931) of the Great Monastery of Derge. At the age of two he was recognized as the 6th Rakra incarnate of Pakshoe monastery in Kham. His father was initially against having his child become a lama, but after the 13th Dalai Lama himself recognized the incarnation, Gyurme Gyatso had to give up his son. His Holiness named the boy Rakra Thubten Choedar.

.

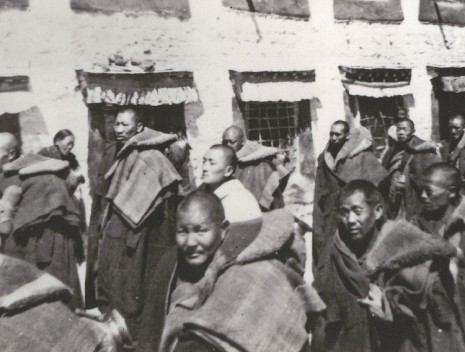

Rakra was first schooled at Pakshoe monastery, but from 1935 he started his formal education at Drepung monastery, specifically Gomang college, Ghungru khamtsen (fraternity). He was a bright child and a fast learner. He was also very lucky to have as his principal teacher a geshe (doctor of divinity) who combined profound erudition with an unusual liberal disposition. This geshe seemed to have left a deep impression on the young Rakra. He often spoke of his teacher much later in life, even in conversations with someone like myself.

My teacher, Geshe Ngawang Palden, was like a father to me. He was very broad-minded, he liked (folk) dancing, he liked singing. He told a lot of good stories. He was very religious.

Normally it takes anywhere from twelve to forty years to master the entire doctoral curriculum which covers every feature of the study of Buddhism, except for the tantric or esoteric studies, but Rakra managed it in ten. At the age of nineteen Rakra Rimpoche received his geshe doctorate degree, in the highest “Lharampa” category.

He then joined the Lower Tantric College of Gyume in Lhasa to begin his studies in Tantric or Esoteric Buddhism. As he did at Drepung, he excelled in his studies. Life at the Gyume College was spartan. It was one of the few monastic institutions in Tibet where the most severe and rigorous interpretation of the Buddha’s vinaya rules were applied to all student monks. The college was also uniquely and uncompromisingly egalitarian and made no exception in discipline or living conditions for high lamas, sons of aristocrats, or someone from a peasant family. Rakra Rimpoche later recalled his life at this college:

I spent the most pleasant and happiest time of my life at Gyume monastery. We were all equal, studying hard, eating the same food, all sleeping in a hall, walking together for long distances. It was a hard life with a lot of discipline.

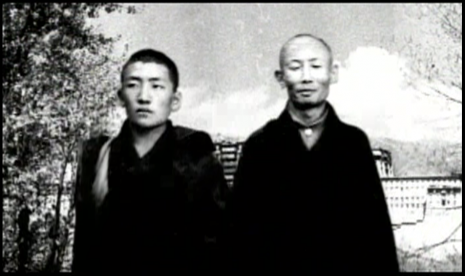

Around this time Rakra also began taking lessons in Tibetan poetry (nyenga), and literature (tsom rig gyutsel) and advance grammar (sumtag) from the great scholar, Gedun Chophel, and got to know him well. Gedun Chophel la was then living in a small apartment at the Gomang Khangsar building in the northern end of the Bharkor area, quite close to Gyume College. Rakra’s older brother Sonam Tomjor, who was then head of the Tethong household, was an intimate friend and drinking companion of Gedun Chophel.

In 1949 at the age of twenty-three, Rakra Rimpoche received the Ngagrampa degree from the Lower Tantric College. In his last year at the Tantric College he was also awarded the rank of gyegoe or disciplinarian.

.

There were not too many geshes in the Gelukpa scholastic hierarchy who had both a Lharampa degree as well as a Ngagrampa degree. It was clear that Rakra was destined for great things in the official church, possibly even the ultimate rank of the Ganden Tripa, the Enthroned of Ganden, which in the Gelukpa hierarchy is the highest theological and academic position.

But the next year he gave up his monastic vows to his root guru Mogchok Rimpoche. His brother, Sonam Tomjor, had already left Lhasa for India after being appointed assistant to the Tibetan trade agent in Kalimpong. His older sister Lobsang Deki Lhawang (my mother) left Lhasa for India in September 1950, about a month before the Communist attack on Chamdo, with Rakra Rimpoche and myself. I (JN) was a year and half at the time, and have nothing but a faded old photograph of myself as a baby with my mother and Rakra Rimpoche on the roof of our house in the Banakshol suburb of Lhasa, to assure me I was really there at the time.

.

In Kalimpong, Rakra began studying Sanskrit under the Russian orientalist George Roerich, to whom Gedun Chophel had forwarded a letter of introduction. Rimpoche continued his Sanskrit studies at Shantiniketan, Rabindranath Tagore’s famous university, where he was also introduced to Indian and Western painting and art. The University wanted Rakra to stay and teach Tibetan language and Buddhism, but Rimpoche received a Government of India scholarship to continue his Sanskrit studies under professor Vasudev Gokhale at the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute at Poona.

.

In 1956 Rakra joined the All India Radio, Tibetan service, and worked there till 1960. He also worked as an assistant lecturer in Sanskrit at Delhi University. In 1959 he married Samten Dolma Lharjé of Phey, Ladakh, who was working in the Kashmir Service of AIR. Dolma la’s family were descendents of traditional Ladakhi physicians (lharjé). Her father was a well known doctor in the district.

In 1960 Rakra was asked by the Dalai Lama’s brother Taktser Rimpoche, to take charge of Tibetan refugee children at the Pestalozzi International Children’s Village in Switzerland, set up for displaced European children after World War II. Rimpoche had wanted to continue his studies in Tibetan and Indian Buddhist literature, and had hoped to do research in England, but he realized the urgency of the task at hand and did as he was asked.

.

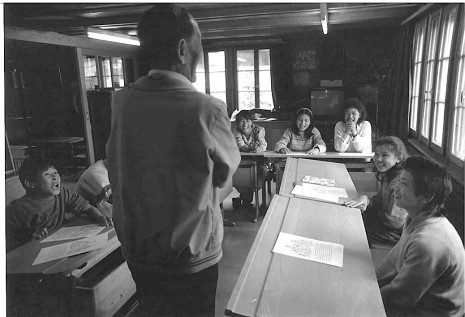

Rakra, his wife Dolma la, and twenty Tibetan refugee children started life at the Pestalozzi Kinderdorf, in October 1960. The Tibeter Heim, “Yumbu Lakang” was, a three-storey Swiss chalet and did not have a Buddhist chapel, so Rakra set about rectifying that. He designed a traditional altar and personally sculpted a clay statue of the Buddha that took the focal place in the dining room chapel, where before their meals the children chanted their Buddhist choepa or grace. A large portrait in oil of the Dalai Lama was also installed there.

Rakra Rimpoche also made his own Tibetan text-books for his children. I remember a Children’s Life of the Buddha that he wrote and illustrated with his own sketches. He photocopied the pages at the Pestalozzi office, and stapled them into booklets. Rakra first brought out this booklet in 1983 but it was later published by Mrs. Taring in India in 1995.

Though Rakra was a skilled practitioner of classical Tibetan he thought that a more demotic written language should be used in journalism and primary school education. He was also not too happy with the quality of the textbooks produced by the exile government. He explained his views in an interview:

I have tried many times to persuade the Tibetan government in Dharamsala to produce simple children’s books or a newspaper written in the common spoken language instead of the scholarly language, so that ordinary Tibetans would have something to read. Many Tibetans don’t agree with me, but I believe that we have to change. The literary language doesn’t help the education of the ordinary people. It leaves them uneducated. The language that is taught to the Tibetan children in Dharamshala is mostly the literary language, which children cannot use in daily life since the literary language uses a different vocabulary, conjugations and structure from the ordinary spoken language.

I have written a few children’s books for the Tibetan community here using the spoken language and I would like to transcribe Tibetan literature into the common language. Tibetan education is still too elitist.

.

Over the years while educating his many children to be good Buddhists and Tibetans, Rakra kept up his own writing, producing a steady flow of books and pamphlets published over the years, mostly by the Library of Tibetan Works and Archives (LTWA) at Dharamshala. He wrote a supplement for his teacher, Gedun Chophel’s translation of the Indian epic, Ramayana, the conclusion of which had unfortunately been lost. He also worked on what Hugh Richardson called Gedun Chophel’s “Unfinished”, his White Annals, The Political History of Tibet, and completed this important work up to the end of the Imperial Age.

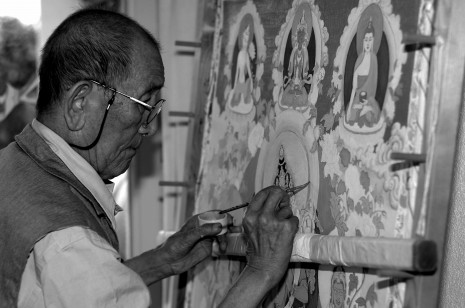

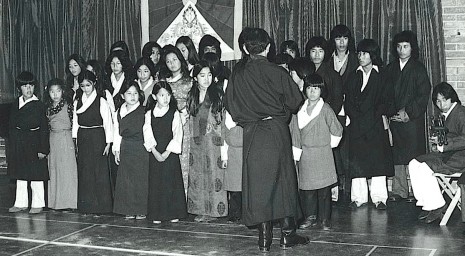

He also painted and sketched: traditional thangkas, oil paintings and even little cartoons to amuse his children. Rimpoche’s artistic work reveals not only some of the naturalism of his old poetry teacher, Gedun Chophel, but also the influence of the Indian modernist tradition, possibly from his time spent at Shantiniketan and its famous art school Kala Bhavan, whose principal Nandalal Bose was much influenced by the Buddhist murals of Ajanta. Rakra Rimpoche wrote plays for his children to perform and designed the costumes and sets himself. He taught them, even the girls, monastic dances, and had them perform at the Children’s Village events.

.

Rakra Rimpoche lived his life fully. Although not obliged to, as he was not a Swiss citizen, he joined the national service as a voluntary member of the Trogen Fire Brigade, and had good memories of working and (afterwards) drinking with other firefighters, mostly Swiss farmers and pastoralists (bauer).

He enjoyed a couple of bottles of “Shutzengarten” beer every evening, and the occasional glass of Dol, the local red wine. He had to have his pipe. He was a good husband and a conscientious father, not only to his own children but to the many other Tibetan children he raised. They all called him “Pala” and probably still remember the ghost stories he told them: the “Pig-headed Demoness of Chamdo” (chamdo phagjoma), “The Ghost of Drayak” (drayak dongdre) and certainly the “Donkey-headed geshe of Drepung” (drepung geshe bhungu).

.

Rakra Rimpoche was a good cook, an expert at making sha-bhalep (Tibetan empanadas) especially the soft delicious Mongolian kind. Rimpoche also made amazing pizzas, and could effortlessly cater to his very large and often extended family – and many friends.

.

Though he kept up his religious practices in an intensely dedicated and wholehearted manner, he was one of the few eminently qualified lamas who never gave public religious teachings, especially in an institutional setting. He taught Buddhism to his children and was open to discussions and questions on religion. He was very patient with me, and conscientiously answered my many and probably sometimes naive questions on the subject. The conventional lecture format seemed to disagree with Rimpoche who was easygoing and a bit of a wag. When AMI arranged for him to give some public lectures in Dharamshala he would invariably wander off topic and end up telling an unrelated joke or a story.

Like another incarnate Lama, the late Taktser Rimpoche (the Dalai Lama’s oldest brother) who I knew well, Rakra Rimpoche was someone with whom you did not have to stand on ceremony. Though both lamas had been educated and raised in an ancient religio-academic tradition, both, nonetheless had ideas and attitudes that were refreshingly contemporary, rational and humanistic. In fact both had the good sense, even the good taste, to harbor serious doubts about the fundamental trulku institution that had produced them in the first place. Professor Paul Williams in his book on the Sixth Dalai Lama, mentions that “Rakra Trulku frankly admits that he does not like the trulku system. He refers to a case where the reincarnation of a teacher was supposedly discovered among Tibetan refugee community in India, only to find subsequently that the teacher was alive in Tibet”

Rimpoche kept on writing till his last days. He managed to finish a translation of the travels of the earliest Chinese traveler to India, the monk Fa-hien (faxian) (CE 399-414) in search of the vinaya-pitaka texts (dulwa). He was assisted in this project by his younger brother Tsewang Chogyal. In this translation published by LTWA, Rakra included accounts of early Buddhist sites in India, to complement Fa-hien’s original travelogue. He also completed his first draft of the history of the Tethong family. I spent four days in Switzerland in the summer of 2011 helping him with the fact-checking. That was the last time I saw him.

.

Rakra Rimpoche passed away on July 10, 2012, at the age of 87. He is survived by his wife Samten Dolma, his daughters: Tsering Choezom, Tenzin Choezom, Ganden Choezom, his sons: Tenzin Wangpo and Rinzin Wangpo, and many grandchildren.

His family members are gathering at Rikon monastery on the 30th of June to observe Rakra Rimpoches longchö, the one year ritual observance of his passing away.

On the 10th of July the Library of Tibetan Works and Archives, which has published four of Rakra Rimpoche’s books, and Tashi Tsering la, director of the Amnye Machen Institute are organizing a public exhibition off the literary and artistic works of Rakra Rimpoche at the the Library premises at Gangchen Kyishong, Dharamshala.

(I must thank Tsering la, Ganden la, Wangpo la and TC la for information and photographs; and Tashi Tsering la for meticulously checking my piece and providing more accurate dates and names where I had stumbled.)

.

What a great loss for the whole of Tibet. Thank you very much,Jamyang Norbu la for sharing the story with us.I am certain that, it hasn’t been easy for you to do this. But you did it any way for a greater and a broader cause to share this very close and intimate story of your family which is also our history we must know and understand.Do accept my condolences upon the loss of your great uncle and Tibet’s one of the most heroes and a scholar as well as your late mother. I only came to know of her passing away from someone’s comment on one of the articles on your blog; Shadow Tibet.Do convey my deeply felt condolences to your sister Rigzen Dolkar la as well. Thank you !

Your simplicity is my owner

Your wisdom is my future

Your compassionate is my present

You are the one my master

I salute you deep in my heart

I miss you lot { RAKRA RINPOCHE }

I had the great privilege to have known Rakra Rinpoche during the last twenty years of his life. Besides his amazing erudition, he was the most gentle, caring and entertaining person I ever met. Visiting him and Amala (his wife) are the fondest memories I have of Tibetans in Switzerland.

I had first met him in the early 1990s when I interviewed him on Gendun Choephel for the journal Lungta I was then publishing. It was a nonstop delight to listen to his anecdotes, including his pilgrimage to India in company of Gendun Choephel’s “Lam-yig”, the scholar’s guide-book to the holy places of India. I also had long conversations with him on Tibetan typography: Rinpoche had worked on a prototype of a Tibetan IBM Selectric typewriter (a model where the typebars were replaced with a spherical element, a “typeball”), for which he had designed all the glyphs. The typewriter was never commercialized, as chances for IBM to make money were to small, but Rinpoche had definitely enjoyed the experience.

I badly miss him.

Thank you for sharing this beautiful eulogy. It is a sad thing we are losing our national treasures.

It is very nice to know about these kind of information which are of historical importance to us.. as being born n grown up in exile we rarely know about these eminent figures of our society.. I respect on your depth knowledge about our history.. so it would be highly appreciated if you would keep on writing about our history which could be either good or bad…

I don’t feel good when you write about something that help to disintegrate the unity among our people… however, If your every point is base on factual ground with evidence then it is worth to be noted and rectify accordingly even if it is against our tradition or culture, yet when I read your articles mostly are either conjecture or subjective.. and that is not very helpful..

so it is my humble request that to kindly write more about historical related issues of Tibet which are more informative and helpful…

Thanks

Dear Jamyang Norbu la,

I worked as assistant to late Bakula Rinpoche for many years and had once traveled with him to Switzerland. Rinpoche knew Rakra Rinpoche very well and of course his wife Dolma la and we spent a day with the family. Rinpoche and Dolma la also visited Ladakh quite often. His passing away is indeed a great loss to us all.

Thank you for presenting the life of Rakra Rinpoche to the world. Unfortunately, people come to know of such luminaries only after they are gone, sadly. A truly inspiring story.

I miss him, and Ama Dolma and the whole family! Was nice to meet them!

Rest In Peace Pola Rinpoche…May your legacy last for the ages and your descendants will always remember and honor you as one of the great poets & scholars of Tibet. “May his passage cleanse the world”.

Very interesting and so well written !

A beautifully-written tribue to a master which would have been fulfilling to meet.

thanks a lot and more important to know about Rakra Rimpoche who is the important and educated person in tibet society

important for people to know. thank you for writting this. Rakra Rimpoche not only very accomplished, but seems like a genuinely kind and good person.

Off course, i like very much to see the old pictures. very nice.

Jola – Thank you for writing this. It’s beautifully written and a gift for all of us who miss Augula very much.

Sir JN, if you could, make some changes in this tribute by showing some of rimpochec’s poems in Tibetan form or provide links where we can read them. Thank you

Rinpoche’s praise for Shakadpa’s book was stunning- i can wait to read in TIbetan.

I would also like to read “Khe-drong-yak sum gyi lo gyue” as i am doing research on Yaks. Jamyang la please help me find a copy.

Also, i would like to read Tethong family’s history- i have heard that they are from Ngari- Chipta pon family. is that true???

Agu Tonpa.

What an interesting story. Like many young Tibetans growing up in exile, I never had the privilege to meet Rakra Rimpoche. But I remember reading his biography of Gendun Choephel (dge ‘dun chos ‘phel gyi rab ‘byed–introduced to me by another great contemporary Tibetan scholar Naga Sangye Tendar). Judging by the cover of this book, one may assume that it is just another boring Tibetan language book (or “too elitist”). But, what really caught my attention was the colloquial style in which the biography was written. I never thought a text written by a Tibetan Rimpoche would be so easy to read. I now feel grateful to Rimpoche for not having written his Gendun Choephel’s biography in traditional Tibetan monastic style and thus making it accessible to young Tibetans (only if they read and not put off by the cover design). I am now also wondering what influence Rimpoche’s writings have had on Tibetan literature in exile. How much of Rimpoche’s style of writing influenced later writers like Pema Tsewang Shastri, who wrote Cold West and Warm East in a similar style?

What an interesting story. Like many young Tibetans growing up in exile, I never had the privilege to meet Rakra Rimpoche. But I remember reading his biography of Gendun Choephel (dge ‘dun chos ‘phel gyi rab ‘byed–introduced to me by another great contemporary Tibetan scholar Naga Sangye Tendar). Judging by the cover of this book, one may assume that it is just another boring Tibetan language book (or “too elitist”). But, what really caught my attention was the colloquial style in which the biography was written; I never thought a text written by a Tibetan Rimpoche would be so easy to read. I now feel grateful to Rimpoche for not having written his Gendun Choephel’s biography in traditional Tibetan monastic style and thus making it accessible to young Tibetans (only if they read and not put off by the cover design). I am now also wondering what influence Rimpoche’s writings have had on the Tibetan literature in exile. How much of Rimpoche’s style of writing influenced later writers like Pema Tsewang Shastri, who wrote Cold West and Warm East in a similar style?

Dear Jamyang-la,

Many many thanks Jamyang-la. I have always categorically valued your writings on literary, cultural, political and historical events with tremendous joy MINUS your ill comments about His Holiness the Dalai Lama which is very very unfortunate.

I remember meeting Rakra Rinpoche in 1992 in Italy during the 2nd International Conference on Tibetan Language organized by Namkai Norbu Rinpoche. Rakra Rinpoche told me, “You people, who are young, must know that we have only our Dharma and Culture as the most treasured wealth. It is only this that makes us proud as Tibetans around the world. What else can we count on… So, must be a good reader…….” Indeed, Rinpoche always shined like a GEM. He was always joyful, open minded and over all a down to earth human being. To me, that means, he has the real Dharma – the SIMPLICITY in the core of his heart. What a great loss!

Tsepak Rigzin

Atlanta, GA

Thank you Jamyang-la for this wonderful and detailed account of Rakra Rinpoche’s life. as always your writing is an inspirational delight for us. Could you please tell us as to where can we acquire the book; “Khe-drong-yak sum gyi lo gyue” ? Thank you so much once again for the memorable pictures.

Dear Jamyang la,

Thank you writing this article so well and imformative. I’d have never known the great Tibetan scholar, Rimpochela, if you hadn’t taken such precious time to share his immense contribution to the Tibetan community. I wish I had met him. His loss is a loss for the whole Tibetan community.

Thank you again and I enjoy your descriptive and educational articles.

Love,

Paldon

Rakra Rinpoche, is a great Tibetan scholar, and qualified Khewang. Has our Tibetan Administration honoured him suitably for his literary contribution? I hope he has been recognized and if not, the administration must do so. Dharmasala has a tendency to ignore great men whose contributions are buried silently, while credit is taken or reserved only for the Dalai Lama.

Story is beautiful.

Since when Buddhist Tantra or Tantric Buddhism is Esoteric? Is it Esoteric only for the writer?

Thank u jamyang norbu la. Since your writings on rakra rinpoche everybody is now talking about it. It shows how much influence you had in tibetan society, no matter what the exile authorities takes on u.

Dear Jamyang la,

When will we see a transparent article on Tibetan Three Musketeers (Lobsang Sengye, Lobsang Nyandak & Kelsang Dorjee). Their plans and tactics.

The other day, someone in our connversation brought up story of this x-monk rinpoche as scholar of Tibetan culture, not really specific, but usual general field. He even compared him as Gedun Choephel. I was curious to ask what is his real produced works in this generic Tibetan culture in which he is supposed to be a scholar. He got nothing specific intellectual works to show by this deceased x-rinpoche. He finally came up with this phrase, rakdra was a student of gechoephel, so he is supposed to be one like him. Well, Gechoe’s literary contriution is availale if one is interested….I can get couple of them from my local library. Looking forward some suggestions from this unknown scholar’s work from his admirers.

NG

NG’s # 1 khewang is Lobsang Sangay.That says it all.

superb

Yas, i agreed with NG of #26 n @27 u must dumbest ass pie e JN haha

The story of Rakra Rinpoche is very touching and I feel that we have sadly lost a great scholar in his untimely demise.Unfortunately, we have again failed to give recognition to such a great man in life.The story of Rinpoche is, no doubt,our story and it is the story of tibetan people.We should contact his family and request them to allow any interested person to use and publish the remaining poetry or untold stories that may have been left behind by late Rinpoche.

I have my highest of respect to Jamynag Norbu la and his works are very educating and provides us substance for discussion

Wikepedia/Encylopedia

Standard Tibetan is the most widely spoken form of the Tibetan languages. It is based on the speech of Lhasa, an Ü-Tsang (Central Tibetan) dialect. For this reason, Standard Tibetan is often called Lhasa Tibetan.Tibetan is an official language of the Tibet Autonomous Region of the People’s Republic of China. The written language is based on Classical Tibetan and is highly conservative.

#26

NG:

Don’t be such a debbie the downer. Just look at his thanka paintings and woodwork above. And if you are not satisfied with the list of his works that JN provided time to visit the libraries. If you can’t see La Tour d’Eiffel that doesn’t mean the grand old lady doesn’t exist.

Dear Jamyang la,

despite being your regular reader, I only stumpled upon your obituary today. I think I got some relevant photographic documents to share – relevant in respect to rakra Rinpoche and in respect to your childhood in Lhasa. Please, let me know where to send them.

With best wishes Stefan