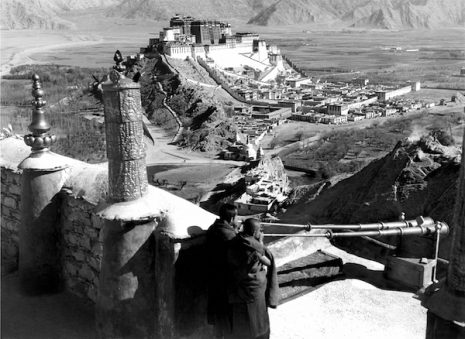

The Russian explorer Nikolay Przhevalsky in 1878 described Lhasa as the “Rome of Asia” We know that since time immemorial, an unending stream of pilgrims, mendicant and merchants flocked to that city particularly during the period of the New Year and the Monlam festival. Early accounts even refer to Armenians, Pebouns (Newari), Casimiris (Muslims), Mongols, Chinese and “Muscovites” among these visitors.

It has always intrigued me what these visitors did at meal times. Tsampa is travel food without peer, but you can have too much of a good thing. Surely these visitors would have sought an alternative dining experience once they hit the Holy City. There is little to no Tibetan textual reference to restaurants, taverns and tea-houses in the Holy City, but that is almost certainly because of the religious nature of much Tibetan writing. Melvyn Goldstein tells us that the general conservatism of old Tibetan society constrained respectable folk from eating in restaurants, frequenting tea houses or even purchasing bread from food stalls. He gives us this verse:

Sol-jha ngarmo zhes khan, zimshag maypai tag ray

shespag kog khun szhes khan, sol shib mey pae tag ray.

Drinking sweet-tea, is a sign of not having a home

Eating kogun bread is a sign of not having tsampa (at home).

I was provoked into investigating this food mystery by a good friend (and pain-in-the-butt contrarian) who once argued with me that there were no restaurants in old Lhasa except for Chinese ones. I did not punch him, but later in the tranquility of my study I asked myself who besides the pilgrims and traders would have needed lodgings (tib.neytsang), and restaurants (tib. zakhang) in Lhasa, yet, unlike our humble pilgrims would have left some written accounts of their travels? And then it struck me. Why, spies and explorers, of course. I came across scattered references to eateries and inns in the reports of the “pundits”, the native spies and surveyors the British first sent into Tibet in the 1860s (eg. Nain Singh, AK (Kishen Singh) Urgyen Gyatso and others), but disappointingly few details.

I hit pay dirt with our great scholar (and spy) Sarat Chandra Das, who in 1879 writes of this establishment in Shigatse: “On one side of the market-place is a large zakhang, or restaurant, where Phurchung and Ugyen (Das’s companions) went to appease their hunger. While they were busy … the proprietor came in. He was a nobleman of Tashilhunpo, head of the Tondub Khangsar family, and held the office of Chyangjob of the Tashi Lama … The lady under whose immediate supervision this establishment is no less a personage than the wife of this dignitary.

I hit pay dirt with our great scholar (and spy) Sarat Chandra Das, who in 1879 writes of this establishment in Shigatse: “On one side of the market-place is a large zakhang, or restaurant, where Phurchung and Ugyen (Das’s companions) went to appease their hunger. While they were busy … the proprietor came in. He was a nobleman of Tashilhunpo, head of the Tondub Khangsar family, and held the office of Chyangjob of the Tashi Lama … The lady under whose immediate supervision this establishment is no less a personage than the wife of this dignitary.

Her head-dress was covered with innumerable strings of pearls…Although she belongs to one of the richest and noblest families in Tsang, besides being connected with family of the Tashi Lama, yet she does not feel it beneath her dignity to keep the accounts of the inn and superintend the work of the servants.”

The explorer L.A. Waddell who was in Lhasa in 1904 with the Younghusband Expedition notes: “Restaurants are plentiful over the town; two large ones adjoin the great square of the market-place. One of them could accommodate about a hundred people. In these places and in the private houses a good deal of beer is drunk, but not much drunkenness or brawling was noticed.” So, all in all, not only were restaurants “plentiful” in Tibetan cities but a number of them were large establishments, owned and run, in some cases, by respectable if not high-ranking people .

The explorer L.A. Waddell who was in Lhasa in 1904 with the Younghusband Expedition notes: “Restaurants are plentiful over the town; two large ones adjoin the great square of the market-place. One of them could accommodate about a hundred people. In these places and in the private houses a good deal of beer is drunk, but not much drunkenness or brawling was noticed.” So, all in all, not only were restaurants “plentiful” in Tibetan cities but a number of them were large establishments, owned and run, in some cases, by respectable if not high-ranking people .

According to the Chinese academic Ma Lihua there were “forty-eight wine shops in Lhasa”. Rebecca French, an American scholar on Tibetan law writes that taverns (tib: changkhang) were not taxed or regulated over much, but if there was a problem like a brawl and someone was hurt than the tavern would be closed (tib: go-dey gyap) by the police and a case registered at the Nangtsesha court.

The Japanese spy Hisao Kimura has left us a account of Lhasa taverns, which he remembers in his autobiography with great affection. He writes that Lhasa changkhangs were “clean and friendly places which might be frequented by members of all social strata, except for the nobility or the monks. It was a place to drink socially, make friends, do business, and where the most remarkable arrangements could be made for romantic liaisons.”

The Japanese spy Hisao Kimura has left us a account of Lhasa taverns, which he remembers in his autobiography with great affection. He writes that Lhasa changkhangs were “clean and friendly places which might be frequented by members of all social strata, except for the nobility or the monks. It was a place to drink socially, make friends, do business, and where the most remarkable arrangements could be made for romantic liaisons.”

Chinese restaurants probably made their appearance in Lhasa in the wake of the Manchu expeditionary force of 1728. Tsepon Shakabpa’s in his history writes that when the Tibetan ruler Sey Gyurme Namgyal was treacherously murdered by the two Manchu ambans, Fucing and Labdron, there was a major riot in the Lhasa. An enraged Lhasa mob killed the ambans and attacked other Chinese residents in the city including restauranteurs. Shakabpa mentions that many of these people fled to the Potala where the Seventh Dalai Lama intervened to save them.

Shakabpa also mention that during the Great Prayer Festival in 1895 when the young Thirteenth Dalai Lama was passing on the streets in a procession, several Chinese people watched the procession from the upper story of a restaurant owned by a Chinese man named Tsungshang Yehrin (?). There was near riot in the city over this act of sacrilege, and the accused Chinese were punished and sent back to China.

The most famous restaurant in Lhasa was established by the Tibetan military commander, Tsarong Dasang Dadul, after the explusion of the Manchu army in Lhasa in 1912. It was called Chindai Zakhang, Chinda being the contraction of chikyap dapon or chief general. It was next to the old Tsarong mansion (later Pangdatsang house) in south-east Bharkor. It probably started off as a place for Tsarong’s soldiers to eat during the uprising against the Manchus but later became a kind of officer’s club and fancy restaurant with a great menu, according to my uncle T.C. Tethong, whose father was a general under Tsarong.

It was called Chindai Zakhang, Chinda being the contraction of chikyap dapon or chief general. It was next to the old Tsarong mansion (later Pangdatsang house) in south-east Bharkor. It probably started off as a place for Tsarong’s soldiers to eat during the uprising against the Manchus but later became a kind of officer’s club and fancy restaurant with a great menu, according to my uncle T.C. Tethong, whose father was a general under Tsarong.

The standard food served in nearly all these restaurants and food stalls were momos, shabaklep (empanadas), droba-khatsa (curried tripe) lowa-khatsa (curried stuffed-lung), gyuma (sausages), shaptra (beef julienne stir-fried with whole green chillies and scallions), various breads as kogun, sanga-bhagley, etc. and also sönlabu (pickled daikon radish) which served as an appetizer or side salad.

THE TIBETAN BHÖ-THUK NOODLE

But the mainstay of all Tibetan restaurants in Lhasa and elsewhere was the noodle soup called bhö-thuk, literally “Tibetan noodle soup”. These are hand pulled noodles, as opposed to gya-thuk or Chinese noodles which are long thin hand-cut egg noodles served at official banquets and aristocratic parties. The bhö-thuk should also not be confused with the bhag-thuk, which is a dish of small round whole-wheat dumplings (tib: bhartsa) in meat broth, especially eaten on Tsongkhapa’s death anniversary and the night before Losar Eve.

The bhö-thuk appears to be related to the la-mian of Sining and Lanzhou and the Central Asian lagh-man. But unlike the la-mian which is served in mutton or beef soup the bhö-thuk always comes in a rich yak-bone broth, with a few slices of yak meat from the calf-muscle (tib: nyabri) and green onions as garnish. Another distinguishing Tibetan ingredient in the bhö-thuk noodle is the Tibetan borax soda (tib: bhu-doe) found only in certain dry lake-beds in Tibet which imparts a special taste to the noodles and allows the dough to be repeatedly stretched without breaking. In making the Japanese ramen and its Chinese equivalent the alkaline mineral kansui (found in Inner Mongolia) is used which gives it the needed texture and a yellow color.

Although in the past non-Muslim restaurants in Lhasa also served this dish, it is perhaps likely that the bhö-thuk is the contribution of the Wabalinga Chinese Muslim community of Lhasa to Tibetan cuisine. The fact of this community being “the butchers and market gardeners of Lhasa” in a sense adds to this possibility. The “Wabalinga” khache, who all spoke Tibetan, called this noodle dish bhö-thuk or Tibetan noodle and not lamian.

To digress, the contribution of the other Muslim community in Lhasa to Tibetan cuisine is almost certainly the Tibetanized “curry” (tib: khache-shamdre). Perhaps Tibetan chefs (gyazay machen) got their inspiration for this mild Tibetan curry from the Kashmiri wazwan, a multi-course meal, which was served (in elaborate silver dishes with tall conical covers) during the Eid festival to ministers of the kashag and the regent, by the Tibetan Muslim (Kashmiri/Ladakhi) community of Lhasa.

The great scholar and poet Gedun Chophel was a avid bhö-thuk connoisseur, according to my uncle Tethong Sonam Tomjor who was a student and friend of his. The two of them not only frequented Lhasa restaurants, but would often get a maid or servant to bring the noodles back to the Tethong mansion or Gedun Chophel’s apartment in enamel tiffin-carriers (tib.kutze), so they could carry on their discussions on history and Buddhism without interruption.

My uncle always complained about the quality of noodles at Dharamshala restaurants.He claimed that the closest thing you could find to the bhö-thuk was the “thukpa” served in Bhagdro’s restaurant in McLeod Ganj. Of course without the Wabalinga yak meat and bone broth, there was no way to properly replicate the bhö-thuk of Lhasa in exile. So in Dharamshala you had an unsatisfactory compromise between gya-thuk and bhö-thuk called “thukpa” which was just plain cut noodles in thin mutton broth, with a sprinking of minced mutton as garnish.

RESTAURANT CULTURE IN EXILE

However much an inconvenience the Tibetan diaspora was to the towns and cities of northern India and Nepal, the refugees did make a significant contribution to the food and restaurant culture of these localities. Tourist centers like Darjeeling had high-end places like Glenary’s and Lobo’s (with Goanese bands playing “Besame Mucho”) that served English and “continental” dishes, and there were dhaba style eateries for Bengali tourists, but not much in between for everyone else. Tibetan refugees soon filled this gap with unpretentious restaurants that provided cheap but wholesome food: shaptra or beef julienne stir-fried with whole green chillies and scallions, thukpa or Tibetan style ramen-noodle soup, sha-bhalay or Tibetan empanadas, and most famously, momos or steamed beef dumplings.

The last dish appears to have been a favorite of the great Bengali filmmaker Satyajit Ray, a regular visitor to Darjeeling, whose literary creation the detective Feluda and his young side-kick Tapesh also enjoyed when solving crimes in the Himalayas.

These Tibetan refugee restaurants were an immediate success with the local Bhutias, Nepali, Sherpas and the many school and college students of the district – of all nationalities and ethnicities. These restaurants also sold the invigorating tongba or millet wine (drunk warm through bamboo straws). To avert the attention of the police and “revenuers” (urdu. abkari), tables were separated in curtained cubicles, which also allowed dating college students some privacy.

For refugees who had a little capital, these were convenient investments where family members could pitch in, and everyone could, at least, get their three squares. Fortunately for Tibetans, the Chinese population of Darjeeling, descendants of Chinese troops repatriated from Tibet in 1912 and 1918, were near exclusively involved in the thriving shoe manufacturing and retailing business, and had left the restaurant field open to the refugees.

My friend Lithang Athar Norbu had Lhasa Restaurant on Robertson Road. Amdo Jigme ran the popular Freedom Restaurant just outside my school gates at North Point. The Gyadotsang family had the simply named ABC Restaurant, while the Gyaritsang family from Nyarong had the modest Ghangjong (Snowland) Restaurant. The Andrugtsang family had the small, three-table Potala Restaurant.

In Kalimpong the oldest Tibetan establishment was Gompu’s Bar and Restaurant, founded around 1926 by Tsering Gompu and located just next to Maharani Chowk where in the old days you had a bust of Queen Victoria under a pagoda style canopy. You had other smaller restaurants like Sonam’s, T.D’s, Lithang and Sona Restaurant below the motor-stand. Then there was the Tongkor Labrang Restaurant at the gate of the hart bazaar, famous for its delicious sausages. The owners had ties to Tongkor monastery in Dhartsedo in eastern Kham and were said to be saving money to find the next incarnation of their lama. Other monastic organizations in exile trying to stay afloat also started restaurants in various Indian towns and cities, hence you had Gyutoe Restaurant, Gyume Restaurant and others.

In New Delhi, Tibetans who had the money got into the Chinese (and pseudo Japanese) restaurant business catering to the Delhi upper and middle class. If you wanted Tibetan food and chang you went to the Majnukatilla refugee camp. Tibetans restaurants also spread across the Himalayas from Ladakh in the west to Meghalaya and Arunachal Pradesh in the East. Depending on the local culture and conditions, Tibetans made the necessary adjustment to their cuisine. For instance in Shillong, Tibetan restaurants served large pie-like pork momos, to suit the tastes of the local Khasi population.

Tibetan restaurant have now spread all over the world. In the early nineties in New York City we had The Tibet Kitchen and The Angry Monk which not only had wonderful food and great ambiance but were also classy places where you might find Uma Thurman or Kevin Bacon sitting at a table behind you. There was also Lhasa Moon and Tsampa which are now also closed. Are there any Tibetan restaurants left in Manhattan these days? Are Tibetan restaurants sheepishly retreating from prominence and assertiveness – like the freedom struggle itself?

We can thank our lucky stars that in Jackson Heights the banner of Tibetan cusine is still being held high by such great restaurants as Little Tibet, Lhasa Fast Food, Friends Corner, Himalayan Yak and so many others, not counting the fabulous momo trucks that also sell kogun bread and tsampa.  Special mention must be made here today of the compact but amazing Phayul Restaurant, where the owner/chef Dawa Lhamo la still creates authentic Tibetan dishes flavored with such mountain herbs as Shakor Ghangkyel. This establishment also serves the authentic bhö-thuk Tibetan noodle although allowance must be made that beef-broth and not yak-bone broth is used.

Special mention must be made here today of the compact but amazing Phayul Restaurant, where the owner/chef Dawa Lhamo la still creates authentic Tibetan dishes flavored with such mountain herbs as Shakor Ghangkyel. This establishment also serves the authentic bhö-thuk Tibetan noodle although allowance must be made that beef-broth and not yak-bone broth is used.

Before concluding, I must give a lusty shout out to the numerous and exciting Tibetan restaurants in Paris. Here are some names: Pema Thang, Himalaya Tibet, Khatag, Kokonor, Tashi Delek, Lhaasa, Tashi Tagyé, Yak, Lithang, Karma Tibetan, GangSeng, Le Petit Tibet, Zachukha, Potala, Momos du Tibet, Taste of Tibet, Restaurant Buddha, Tibetan Kitchen, Restaurant Tibétain Pays des Neiges and others that I have unfortunately overlooked. It has been many years since I was in Paris but I remember the last time there I was served the fanciest momos I have ever eaten. Not only were the momos themselves exquisite but they were laid out in a floral pattern on an oversize nouville cuisine plate, and served with two distinct sauces, red and green, with their own unique flavors – but not in tiny side bowls as is usually the case. These two sauces swirled around the momos in an intermingling vine-like design.

It was, simply speaking, a small work of art. But I expected no less from a Tibetan chef in the city of light.

(Apologies for not mentioning your favorite Tibetan restaurant in your part of the world. Do let everyone know about it in the comment section.)

References:

Donald Rayfield, The Dream of Lhasa: the Life of Nikolay Przhevalsky (1839–1888).

Melvyn Goldstein, A History of Modern Tibet, 1913-1951: The Demise of the Lamaist State

Sarat Chandra Das, Journey to Lhasa and Central Tibet

L.A.Waddell, Lhasa and Its Mysteries.

Ma Lihua, Old Lhasa, A Sacred City at Dusk, Foreign Language Press, Beijing, 2003.

Rebecca French The Golden Yoke: A Legal Cosmology of Tibet

Hisao Kimura (& Scot Berry) Japanese Agent in Tibet: My Ten Years of Travel in Disguise

Dundul Namgyal Tsarong, In the Service of His Country, Snow Lion, Ithaca, p.48

Shakabpa, One Hundred Thousand Moons, Brill.

Abdul Wahid Radhu, Tibetan Caravans: Journeys From Leh to Lhasa

Satyajit Ray, The Feluda Stories, Viking/Penguin India, 1996

https://www.visitnortheast.com/gompus-hotel-kalimpong.php

The bho-thuk looks so enticing! I could do with some momos as well. Unfortunately,no Tibetan restaurants in Colombo (Sri Lanka).

Thank you for the great article.

Wish you a huge Losar Tashi Delek!

TCL

Jamyang la, LOSAR TASHI DELEK to you and your family.

Thank you for this nice article. Running a restaurant is perhaps one of the most common profession Tibetan refugees engage in, after the sweater business. My Pala and Amala also ran a small restaurant for a few years in mid 70s in Dehradun Cantonment. There were only two items on the menu –

Momo and Thukpa. Their main customers were mainly nepalese soldiers belonging to the gurkha regiment and their families. My Acha la also ran quite a popular restaurant in McLeod in the 80s called Shambahla catering mainly to western tourists. I have been told that you were a frequent visitor there.

Here in Toronto, Tibetan restaurants consistently score the highest ratings on various rating sites like Yelp, and Google. And Momo is as always a big hit.

Fascinating & informative. Thankyou.

Dear J, It’s great to see you writing again! It’s always been my understanding that practically every guesthouse along the main thoroughfares seconded as a restaurant back in the old days. Not that they would offer their guests a huge menu full of choices. Since I’ve been looking at it recently, I can say that William McGovern, author of the 1924 book To Lhasa in Disguise, was fairly obsessed with food while he was traveling in Tibetan areas, even dreaming about a nice pudding or a particular sweet evidently not available where he was. In fact, on one of every 10 pages of his very long book there is some discussion about food. Late in the book, on p. 418, he thinks we would enjoy seeing a listing of his food expenses while he was in Lhasa viewing the Losar celebrations from the window of his room, trying not to get caught. Which reminds me, Tashi Losar! Good health, long life and freedom!

Your’s Dan

Hey Jamyang la, great to see you back. And as always a splendid read.

Even during the times of Milarepa 11AD there were inns in Tibet. Milarepa is said to have set up rendezvous with his fellow classmate is during his apprenticeship years where he learnt Black Magic from Lama known for Black Magic.

Though the Milarepa biography by penned much later in 14/15th century but points to fact that inns were there for pilgrims and travellers.

Tibetan words such as Neystang གནས་ཚང་། (Inn) Ney Po གནས་པོ་ (Host), Ney Mo གནས་མོ་ Hostess in Milarepa’s Namthar are the testament to it.

Jamyang la! Thanks. A great piece on Tibetan restaurant culture. I enjoyed it thoroughly. However, I think you have missed, a signifinant dimension of this culture, i.e. restaurants owned and run by our monastics in-exile in Majnukatilla and in south Tibetan settlements (gzhis chags). I think there is a lot more you could have written on how these evolved and are run – a new culture purely evolved in-exile. May be you do not frequent in these restaurants. Anyway, next time JN la.

Thanks Gen Jayang la, as informative as always and so glad to see your writings,,,,

Great historical piece. When it comes to dish, Tsampa has no match. What a genius invention. It requires no cooking, no refrigerators, easy to carry, good for weeks or months, can be mixed with variety of ingredients for different flavors. And best things about Tsampa is very healthy and nutritious. These days only few people make good quality Tsampa.

Nothing is more delicious than pak mixed with cheese and dry minced meat.

Nomad in Albany, California on Solano Ave. Actually ran into JN la there a few years ago. Great Tibetan food

Fantastic article, thank you for some Tibetan restaurant history. Great website.

Thanks Jamyangla for mentioning Gompus restaurant .

But I would like to add , by saying that Gompu’s was not a restaurant, rather it was a confectionery with a bar attached.

Gompus was established by my grandfather Gompu Tshering in the early 1920s.

An English lady,Tigga ( her nick name ) , her father was the SDO , in those days, and she mentioned the pastries , sponge cakes etc and said those items could have compared to FUllER’s confectionery,at London.