A PRELIMINARY INVESTIGATION INTO THE “DARK UNDERBELLY” OF SOCIAL LIFE IN THE HOLY CITY

This is a preliminary and largely impressionistic overview of a neglected strata of old Lhasa society, and lays no claim to serious scholarship. The spelling of the names of the various groups and fraternities mentioned in this article have been difficult to verify. Where available the correct spelling has been provided but a basic English transliteration has been used for the rest. I wrote this piece for Trails of the Tibetan Tradition, a collection of papers to honor Tibet scholar Professor Elliot Sperling. The book is now available at Amazon. It is my hope that this inadequate study will provide my most learned and steadfast friend, an amusing diversion from his otherwise serious academic routine.

PART ONE

In the annals of true crime stories, I hadn’t quite expected to come across something like this from Tibet. I heard the story of the “Lhasa Ripper” from a well-known Tibetan singer who was a student of mine at the Tibetan Music, Dance & Drama Society (renamed TIPA in 1981) at Dharamshala from 1969 to 70. She insisted that every word was true. We were having a discussion on Tö-shay songs when she told me that her maternal uncle, Töpa Bhu Damdul of Walung, had been a very good musician and had played the Tibetan lute (dranyan) and the hammer dulcimer.[1]

Bhu Damdul was also a successful trader who had a store at Nyanam, on the Tibetan frontier of Nepal. He also conducted a lot of business in Lhasa, and lived there in the twenties and thirties. It appears that he knew such Lhasa musicians as Lutsa la, who later became the senior music teacher at TIPA. Damdul also knew the blind maestro, Ajo Namgyal, who is regarded by many as Tibet’s greatest musician, and who had composed such memorable songs as “Trala Shipa”, “Dawae Shunu” and “Ajo Dhe”.

Bhu Damdul also gambled and ran with the Lhasa fast set and was a close friend of the young Lhasa playboy, Rinzin. Rinzin was a handsome man and a lover of the famous Lhalu Lhacham (Great Lady). Yangzom Tsering Lhalu, nee Shatra or Shedra, (c.1880 – 1962), was famous for her affairs. One paramour, a junior lay official (drungkor) Jingpa composed many loving and witty verses in her praise. The Great Lady might not have exactly have overwhelmed with her looks. She was in fact, somewhat overweight and getting on in years, but was a generous, witty and fun loving woman.

Sir Basil Gould who led the British mission to Lhasa in 1936 (and in 1940 for the 14th Dalai Lama’s enthronement) remarked on her hospitality:

A member of high society was a lady, connected by birth with two previous Dalai Lamas. One of the events of the Lhasa season was an annual luncheon party which she gave to the Cabinet and other high officials. Her hospitality was so urgent that often the fate of at least a few of her guests was “Where I dines I sleeps”. She had a fund of jokes and stories which were reputed to be broad. I doubt whether even in England men and women live on such natural and easy terms as in Tibet.[2]

But the powerful finance secretary and political player, Tsepon Lungshar, was also a paramour of Lhalu Lhacham, and resented Rinzin’s relationship with her. Lungshar had a fine-looking wife but may have maintained his affair with Lhalu Lhacham for its political usefulness. He looked around for a way to get rid of his rival.

At that time (1926-28) Lhasa was shaken by a series of brutal, Jack the Ripper style, murder of prostitutes. A modern police force had been created by the 13th Dalai Lama in 1923-24, and it was possible that this trained modern force might have solved these crimes, but in the period when the serial murders took place the conservative/monastic faction in Tibetan politics (allied with Tsepon Lungshar) had managed to bring about the effective termination of the new police force.

After the 13th Dalai Lama returned from exile in India in 1912, he embarked on a broad modernization program that included the creation of a strong, effective military and also a modern police force for Lhasa. This police force (polisi) replaced the Korchakpa, the old style Tibetan constabulary (skor ’chag pa) and the Manchu Amban’s enforcement unit called the Thuvin, which had carried out the Chinese style tortures and beheadings before 1911. Subsequently all Chinese soldiers, thuvin and Manchu officials were expelled from a newly independent Tibet.[3]

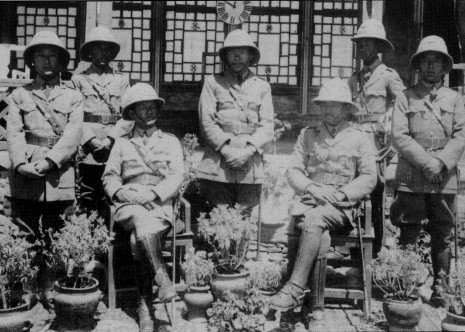

The modern police force was reportedly smart and well trained along British lines. S.W. Laden La, a senior officer in the Bengal police and an ethnic Tibetan (Bhutia), had been sent on deputation to Lhasa to train this new unit. Laden La was appointed Police Chief by the Dalai Lama himself and also awarded the title of Dzasa.[4]

Colonel Bailey, The British Political Officer in Sikkim, visited Lhasa in July 1924. In his report he mentions: “Laden La has organized a very creditable police for Lhasa city. The men are smart and dressed in thick khaki serge in winter, and blue with yellow piping in summer. They are stationed in different parts of the city (in police boxes. JN). The fact of their presence has reduced crime in the city considerably and the inhabitants appreciate this.”[5] The police force also had a bagpipe band (Tib: pegpa), which Bailey took credit for introducing. My late mother remembered that as a child she would approach the Banakshol police box close to her house, and hold out a British Guard doll (with Bearskin cap) that her father had brought her from India. The policeman on duty would give it a smart “present-arms” salute with his rifle.

But the monasteries and the conservative faction hated the new army and the police. With the help of Lungshar they succeeded in getting the commander-in-chief, Tsarong Dasang Dadul, removed from power in 1925, and over time managed to effectively emasculate the military and the police. The decline of the latter force was particularly dramatic and striking. The smart, modern, well-trained and effective police force was disbanded and terminated for good. It was replaced by a ragtag band of peasants called “Lha-Ngam-Phun Sum”[6] conscripted from the districts of Lhatse, Ngamring and Phuntsokling in Tö or Western Tibet, for which they received tax exemptions on their farmland. (The peasants of Tö when properly trained and equipped could prove to be formidable soldiers. The reputation of the Dhingri regiment is second to none in the history of the modern Tibetan army.) But the untrained peasant policemen now just sat inside their police boxes chanting mantras and repairing the soles of Tibetan boots (lham dokpa gyab) to eke out their miserable pay.

Finally, in late 1948, the peasants were sent home and a proper police force created as a part of the Tagtra administration’s broad (but inadequate) response to the emerging threat of a Chinese invasion. The Old Zimjung Makar the traditional “Inner Chamber” guard unit of the Dalai Lamas had been converted to an artillery unit when it was replaced by the modern Guards regiment (Kusung Makar) in the 1920s. This artillery unit was converted to the new Lhasa police force in 1948, but retained within the army as the 6th Chhadang regiment .[7]

Although it never quite reached the standard of Lhasa’s first modern police force, this police regiment retained the bagpipe band of its predecessor, and distinguished itself in the March Uprising of 1959, defending the Jokhang against PLA infantry, artillery and tanks. The fact that it had earlier been an artillery regiment contributed to its effectiveness. It is now stuff of legends how the famous police officer Major Rinzin Penjor (aka Rupon Gura) and some of his men, assisted by volunteer citizens of Lhasa, dragged a couple of howitzers around the Barkhor and blasted away at Chinese positions.

_______

After Lungshar manipulated the dismissal of Tsarong he was also able to have an interim C-in-C, Drumba, summarily dismissed. Eventually in 1925 Lungshar insinuated himself into the supreme position of commander-in-chief of the army and also of the metropolitan police force.

It was probably after this triumph that he used his position to have his rival Rinzin, and Rinzin’s friend, Bhu Damdul, arrested for the murder of the prostitutes. Both Rinzin and Damdul had frequented such women, and when one day a prostitute with whom both men were friendly was murdered, Lungshar acted. Rinzin and Bhu Damdul were arrested (possibly around 1928) flogged and imprisoned. Whether the decline of the police force prevented the discovery of the real murderer is, of course, a matter of conjecture.

The case was only solved in the mid-1930s, and that too more by luck than anything else. During the Monlam festival when the monk magistrates of Drepung took over the legal duties of the Lhasa administration, a monastic disciplinarian Chabdam Ugen arrested a minor monk official who went by the nickname of “Chonzay Serso Chenpa” or “official with the gold tooth.” This official who was a khatsara, a Nepalese national, happened to be talking to someone else in Nepali (which Ugen understood) at a tea-shop in Lhasa, where Ugen happened to be present. One informant told me that earlier in life Ugen had lived in Kalimpong as a petty trader where he picked up basic Nepali. Someone else told me that Ugen had learnt the language when he traveled to Nepal in one of the official Tibetan government missions (bhayul ten-sheng) organized every four years to make make offerings to the three great stupas around Kathmandu.

So Ugen overheard the conversation that revealed Chonzay as the serial killer of prostitutes, and also that he was preparing to seek asylum at the Nepalese consulate. Ugen immediately hit Chonzey hard with his heavy whip handle and placed him under arrest. Chonzey cried out that he was a khatsara and claimed immunity.

Ugen is supposed to have replied sarcastically “If you are a khatsara I am a natsara (khyoe khatsara yina nga natsara yin).” a nonsensical reply playing on the Tibetan word for mouth “Kha” and nose “Na”, meaning that he didn’t care who the man was. The arrest is said to have caused a diplomatic row with Nepal, but Chagtam Ugen became famous because of this feat.

A New Age Tibetan friend of mine to whom I first told this story objected to the very idea of a Tibetan serial killer, but such criminals are not entirely unknown in Tibet. In the early 11th century, during the period of the “Later Transmission of Buddhism” to Tibet (tenpa chi-dhar) we hear of a secret society of monks called Artso Bande Chopgyal (Ar-tsho bande bco-brgyad)[9] that performed savage ritual murders. Legend has it that this and other debased misinterpretations of Tantric practices led to the invitation of the great scholar Atisha from Vikramashila University to purify and revive Buddhism in Tibet.

We also have the story of the sinister “Shagdun Sangye” (Seven Day Buddha) of Ghungthang, a religious charlatan and mass murderer who promised people who undertook a seven day retreat under his guidance a complete dissolution of their corporeal self and a direct entry into nirvana. He accomplished this by dropping them into a bottomless pit normally covered by a retractable floor on his meditation cave. He was eventually exposed by the “divine madman” Drukpa Kunleg, who arranged for him to receive a poetic sort of justice.[10]

But a more relevant objection to the arrest of the Lhasa Ripper by Ugen was raised by a knowledgeable scholar-friend of mine. He told me that he had creditable information that Chabdam Ugen became famous for the arrest of a Nepalese citizen, Sherpa Gyalpo, around 1929 for smuggling tobacco and opium. But the late K. Dhondup has noted that Tsepon Lungshar ordered Sherpa Gyalpo’s arrest and used his own troops to catch this person.[11] Shakabpa does not mention Lungshar but writes that Sherpa Gyalpo was arrested by Nangtesha police.[12] It is possible that Chabdam Ugen broke this case because he overheard incriminating conversation in Nepali between Sherpa Gyalpo and another person and attempted to arrest this miscreant. It is also certain that Sherpa Gyalpo escaped to the Nepalese Legation. Subsequently, armed Tibetan policemen and soldiers forcefully entered the premise and captured Sherpa Gyalpo, creating a serious diplomatic crisis between Tibetan and Nepal. Richardson says that Lungshar had ordered the forceful incursion into the Nepalese Legation and because of his “rash arrogance … Lungshar’s position with the Dalai Lama was greatly discredited.”[13]

One other account I heard was that Chabdam Ugen had not caught a murderer but a well-known burglar called Kuma Kentsug whose modus operandi was to “place a ladder” (ke-tsug) against a courtyard wall and enter houses on the other side. But the question for me was: would Ugen have become famous in Lhasa merely for arresting a thief?

I am willing to accept that the Lhasa Ripper case study I have presented has a number of inconsistencies, but it is my hope that qualified researchers and scholars, especially those with access to Zhol Laykhung or Nangtseshar criminal court records will one day unearth and publish a full and satisfactory account of the Lhasa Ripper. In the meantime, I, as a teller-of-tales, will carry on telling this tale the way I heard it from my primary source.

.

PART TWO

I have long been interested in what might be called the “dark underbelly” of old Lhasa society: the professional gamblers, criminals, burglars, pickpockets, forgers, bandits, beggars, scavengers and even the ladies of easy virtue, though some may object to their inclusion in this class. Granted, this particular dark underbelly wasn’t so “dark” or extensive as that of London or New York, and certainly not as exotic as that of old Peking or Shanghai, I suppose, but it was interesting in its own way because of its medieval flavor, and, as with all things Tibetan, its inevitable though nonetheless odd connection to religious life. Over the years I picked up bits of information, largely in casual conversations with older residents of Lhasa, all of whom have passed away.

THE PROTECTOR DEITY OF LHASA (& ITS CRIMINALS)

My interest was first turned to this subject when as director of TIPA in 1981 I initiated the revival of the Shoton or the annual Opera (Ache Lhamo) Festival that took place at the Norbulingka Palace before 1959. For the first day of the Festival we planned to stage the introductory dances of all the various opera troupes that performed at the festival. When putting together the program I was told by the Opera Master, Norbu Tsering (aka Laba from the English “lover”) that the first performance on the stone-flagged stage of the Norbulingka was not opera but a program of Tantric dances (cham) put on by the entourage of the Karmashar oracle, who was considered the sap-dag or the local deity and chief protector of Lhasa.

Because of this special status the city magistrates from the Nangtsesha court would regularly offer homage to this oracle, and their constables, the Korchakpa, would organize the dance program at the Norbulingka. Although the modern police force took charge of the policing of the city in early 1924, the Korchakpa were not entirely disbanded and served as courthouse bailiffs and deputies. They wore dark wool robes and the yellow bokto hat of officialdom, and had a whip tucked in their belt. These constables were the principal performers of the Cham dance program, with petty criminals, pickpockets, and Ragyabpa beggars serving in the lesser roles.

VARIOUS CRIMINALS FRATERNITIES

From all accounts there was a permanent class of petty criminals in Lhasa city generally referred to as kuma, which would mean a thief or burglar. Among burglars there were specialists. I have already mentioned our “ladder placer”, Kuma Kentsug. Another specialist housebreaker called the Beeg-gyapkhen or “penetrator” (hbegs rgyag mkhan) would noiselessly dig holes in the rammed earth or brick wall of houses and entering the place make off with the valuables. Sometimes a “penetrator” would just scoop out a small hole and reaching in, take what he could grab.

There is a story how such a thief once tried to steal from a solitary meditator. The yogi heard the scratching on the wall of his hut and realized what was going on. He prepared a noose with a length of rope. When the thief’s hand reached in through the hole he lassoed it with the noose and tied it tight to the ceiling. He then took a long switch and went outside where the thief was lying on the ground with his hand stuck in the hole. The yogi pulled down the thief’s trousers and began to flog him. With each stroke the yogi recited the mantra of Jetsun Dolma (Arya Tara) “om tāre tuttāre ture svahā”. After twenty-one lashes and equivalent recitations, the yogi released the thief who ran off as fast as he could, finally taking shelter under a bridge. Lying down to rest the thief began to wonder why the meditator had so consistently recited the Tara mantra with each stroke. As he thought about it he repeated the mantra he had heard, the pain on his butt keeping the memory alive the whole night. Now the meditator was actually a spiritual master who had foreseen that the thief would shelter that night under a bridge haunted by a terrible flesh-eating demon. But as the thief now kept unconsciously reciting the mantra of Arya Tara, the most formidable protector and savior of sentient beings, the demon could not even come close to our lucky “penetrator”.

Another criminal fraternity the Thep-tre (mtheb dres) or pickpockets, was made up of street urchins who were skilled at relieving valuables from within the amba or the front pouch of people’s robe. Their victims of choice were peasants and pilgrims who crowded the streets of Lhasa during the many ceremonies and festivals throughout the year. Thep-tre were said to sometimes use scissors or sharp knives to cut through the fabric of the pouches. They were also much given to shoplifting from the outdoor stalls in the Barkor. When the Communist Chinese occupation force took over Lhasa, I was told that many of the Thep-tre shifted their attention to Chinese troops, relieving them of their watches, wallets and fountain pens, and in the case of the officers, even pistols.

There were no safe crackers because there were no safes in Lhasa, but there were professional lock-pickers Dipzue-gyapkhen (lde-rzus rgyag mkhan) (literally “user of fake keys”), who could take care of the crude but tough Tibetan locks, gochak (sgo-lchags) or door-iron.

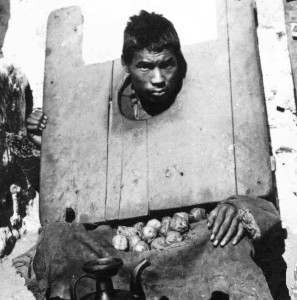

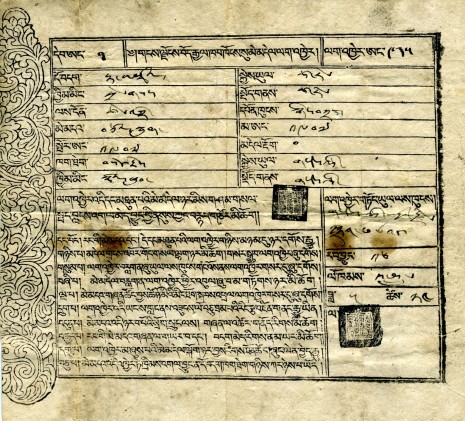

There were also criminal craftsmen who made fake zi-stones and forgers of coins (ngul-zunma-zokhen) and currency-note counterfeiters (lor-zunma zokhen). Bell has a photograph of a prisoner in stocks convicted of counterfeiting currency-notes.[14]

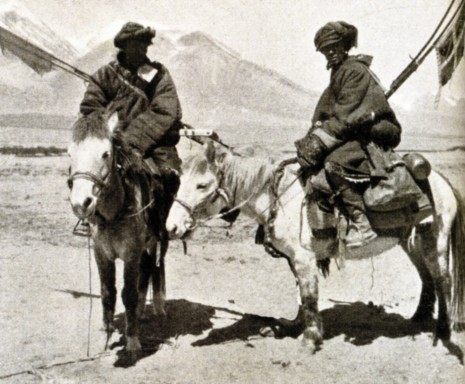

Then there were the Jhagpa, bandits or highwaymen, who were armed – with spears, swords or rifles – and were dangerous. Taktser Rimpoche claims, though, that they could be chivalrous and might leave you enough food, even a mule to ride, after they robbed you.[15] But the chivalry of some of these bandits could be decidedly ambivalent – happily looting monasteries on the one hand while making lavish gifts to their own lamas. A case in point is the Khampa outlaw Dhonyod Dorje who was eventually captured and imprisoned by Gushri Khan.[16] Such bandits did not operate in Lhasa itself, but in many cases visited the city for pilgrimage, trade or even the occasional R&R. Since Lhasa was the “Holy City” I am told that there might have been some kind of unwritten rule granting temporary immunity to bandits coming on pilgrimage. Bell writes about such an informal arrangement for Golok tribesmen visiting Lhasa, but I don’t think it extended to outlaws operating closer to home.

There are probably a number of sociological reasons for the prevalence of banditry in Central and Western Tibet at the beginning of the last century, but one reason may have to do with Chinese misrule in Eastern Tibet. When Heinrich Harrer was traveling through the Jhangtang and Western Tibet he refers to bandits as “Khampas” when in fact the population there is not is not Khampa at all. Some older Tibetans I know have objected to Harrer’s mislabeling, but in retrospect it does appears that quite a few of the major outlaws in those remote areas were Khampas who had been forced to leave Eastern Tibet because of the continual violence and oppression of Chinese administrators.

These fugitives probably first started off as outlaws in Western Tibet, but over time settled down to becoming traders and local leaders of sorts. One of the leading citizens of Mustang in the 50s was Garnag Yeshe Sangpo from Lithang in far Eastern Tibet. He had apparently started out as a bandit on the border of Tibet and Nepal, but through force of personality had established himself as the leading citizen of the town of Marpha, just south of Jomsom.

Many of these “visitors” to Lhasa frequented the chang taverns which ladies of easy virtue would patronize, and gambling parlors (bak-khang) where professional gamblers (bak-pa) would oblige anyone looking for a game of bakchen (dominos) sho (dice), takse (cards) or most likely mahjong. One famous gambler from the forties and fifties known as “Dre Kusho” or Mr.Ghost, because of his extraordinary skills, managed to make it out to India. I saw him in a McLeod Ganj restaurant in ‘69, looking very wrinkled and old, smoking a cigarette from a stylish silver cigarette holder.

In spite of the orderliness of Tibetan society in general, there were often brawls, and even shootings in these establishments. There were no restrictions on ownership and carrying of guns in Tibet, and a variety of weapons and ammunition were sold freely in Lhasa shops – and even by street vendors. With the end of WWII surplus military equipment and gear (including rifles and pistols) were snapped up by enterprising Tibetan traders in Calcutta, Dhartsedo and Lijiang and distributed all over Tibet, especially Lhasa. The Tibetan government probably thought that it was all becoming too much of a good thing and issued an injunction whereby all firearms coming into Lhasa were required to be registered and all owners had to carry a special permit issued by the Lhasa magistrates. I still have the gun-permit issued to my parents when we visited Lhasa in 1949.

.

“LABEL” LADIES OF LHASA

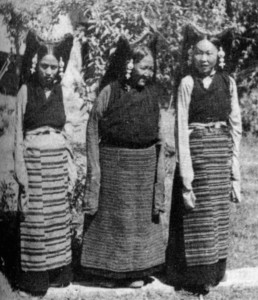

In 1985 TIPA produced a musical tableau vivant on the Dalai Lama’s birthday, called Lhasa Drenlu or “Song of Lhasa Memories.”[17] I borrowed the name of my show from the title of the famous long poem, written by the 13th Dalai Lama’s secretary, Shelkarlingpa. It depicted a street scene in the Holy City where ordinary city folk, aristocrats, lamas and so forth go about their business, while in the background a line of ten dranyen musicians play and sing songs related to the unfolding scenes. I had also included a (pantomime) donkey carrying firewood, Drekar beggars, and two actresses playing the role of the famous singers of old Lhasa, Shimi Lemba (Cat label) and Porok Lemba (Crow Label).

I was taken to task for this production by a Dharamshala mob and later the exile-parliament, and charged with insulting the Dalai Lama on his birthday by showing donkeys and prostitutes. I attempted to argue, quite unsuccessfully, that these two famous ladies were not prostitutes but respectable entertainers belonging to the Nangma musical guild (nangmae kyidug) of Lhasa, who even performed at cabinet banquets (kashag thogtro) in the old days.

The term Lemba for the label or brands of commercial products imported into Tibet was also used to designate certain famous ladies, especially among the Lhasa demimonde, though not all women “labelled” in this way were necessarily prostitutes. For instance a Lhasa storeowner labelled Khatak Lemba apparently just specialised in selling khatags. One lady of easy virtue who is said to have worn Western style shoes (jurta, from the Hindi juta) instead of the traditional Tibetan boot lham, was called Jurta Lemba. One beauty was lauded as Hangu Lemba (Dove Label), while two others (perhaps less well endowed) were dismissed with the unflattering nicknames of Longo Lemba (Sheep Head Label) and Naptug Lemba (Snot Label). My mother told me of another lemba lady (whose name she refused to reveal) who moved to Darjeeling in the early forties and, as Miss Lily, contributed to the War effort by entertaining American GIs on leave in that hill resort.

The ethno-musicologist, Isabelle Henrion Dourcy, in her study “Women in the Performing Arts”[18] provides further details and even a photograph of our two famous “Label” singers. But more relevant to our investigation, her study includes an account of “the most illustrious” of these female entertainers and courtesans, Chushur Yeshe Dolma.

She was born probably around 1915 in the district of Chushur (at the confluence of the Kyichu and Yarlung Tsangpo) and died in Lhasa in 1992. According to Henrion Dourcy “Her beauty was by all accounts irresistible, as were her kindness and generosity. Prostitution at that time did not seem to entail the same cynical commodification as in contemporary Lhasa.” But Henrion Dourcy provides a popular verse from around the fifties that is slightly at variance with her latter assertion. (The translation is partly mine).

.

.

Chu-shur ye shes sgrol ma

tam kar ga tshad gtong ga

sa skya’i rje btsun sku zhab

khan pa rgyab kyang mi dgos

Chushur Yeshe Dolma,

How many silver coins do I have to spend for you?

Even if the Sakya princess gave me a better deal

I don’t want her.

Henrion Dourcy also tells us that “Not only was Chushur Yeshe Drolma a singer, but she could also play the lute.” By all accounts she was an accomplished dra-nyan player. I have a recording of her playing the quickstep section (truk-shay) of the Tö-shay “Draktö Karpo”. Her picking is rapid but smooth, uncluttered and melodious. This audio file was generously shared with me by Phuntsok Jordhen la.

[audio:https://www.jamyangnorbu.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/09-Drakthoe-Karbu-Dramyen.mp3|titles=Draktö Karpo played by Chushur Yeshi Dolma].

For other anecdotes on the courtesans that inhabited the Lhasa taverns (changkhang) I can find no better informant than the Japanese secret agent, Hisao Kimura, who appears to have spent a lot of his time in Lhasa at these establishments. I met Kimura san in 1988 at the Tibetan New Year (Losar) reception of the Tibet Cultural Centre at Tokyo. He was quite old then but still spoke fluent Tibetan and still seemed to have an eye for the ladies.

A Lhasa changkhang might be frequented by members of all social strata, except for the nobility or the monks (although warrior monks were known to break this rule). It was a place to drink socially, make friends, do business, and where the most remarkable arrangements could be made for romantic liaisons.”

(On Kimura’s initial venture the lady of the establishment took him in hand. JN) “My, you are inexperienced, aren’t you? Well, we’ll soon fix that. You see, many of our Lhasa girls have no objection to spending time with a man, or to making a little extra money. Some of them are widows who might be lonely, and some are girls saving up for their marriages. You just name the lady and I’ll try to arrange something. If you have no one in mind, just leave it to me to arrange something to your satisfaction. We have rooms upstairs and a back door.”

She explained all this with a twinkle in her eyes but without a trace of lewdness. It seemed like an innocent game that everyone enjoyed. Even so, I found myself a little embarrassed as she told me how much money it would take … Not all girls, of course would consent to such arrangements, but there seemed nothing particularly low or immoral about those who did. It all seemed remarkably friendly and healthy. It could not really be called prostitution: just good clean fun and a little money made on the side.” [19]

.

PROFESSIONAL AND SPIRITUAL BEGGARS

The leading guild of professional beggars/scavengers/undertakers was the Ragyabpa that nearly every Western visitor to Tibet before 1959 has mentioned in their accounts. The duties of the Ragyabpa were supervising the other beggars of the city and also carrying the corpses of indigent people to the cemeteries for disposal. Some accounts maintain that Ragyabpas performed the actual “sky burial” or more correctly, jha-tor, the cutting up of dead bodies and feeding them to the vultures. But that task is more generally performed by the Tomden fraternity whose members do not beg and who are considered somewhat more respectable than Ragyabpas. Tomdens also perform autopsies for the courts when required. I have been told that through their traditional knowledge and experience of dissecting bodies the Tomden are familiar with symptoms of poisoning or other forms of unnatural death.

Ragyabpas claim that their actual name rags-brgyab pa (dam builder) derives from their original occupation during Songtsen Gampo’s time, when they were entrusted with monitoring and repairing the dykes of the Kyichu river which was then close to the city. But in later years as the river shifted its course in a more southerly direction, they took on their present duties. The leader of the guild is called the Ragyabpa Pombo and he wears the official bokto hat of respectability and the sogchil earing. Harrer in his Lost Lhasa has a photograph of Ragyabpa men and mistakenly explains their headgear in this way. “Here they wear round government-officer hats, which they found in the thrash.” Sarat Chandra Das met one Ragyabpa pombo on his journey to Lhasa in 1882: “At present the chief of the ragyabas is a man of about fifty years called Abula; he wear a red serge gown and a yellow turban.”[20] Das tells us that Shigatse also had its Ragyabpa guild.

All visitors to Lhasa from the British mission, Chinese mission, the Nepalese and Bhutanese representatives, even visiting individuals of wealth or distinction were obliged to pay the Ragyabpa a certain (not insignificant) amount, as a mandatory tariff on entering Lhasa. This even included important visitors from Kham and Amdo as lamas, chieftains and merchants. It was said that the Ragyabpa would curse you if you didn’t pay and a Ragyabpa’s curse was considered malignant. This was essentially a kind of cultural extortion, resembling the practice of the transgender Hijra community in India that still derives its income from similar begging/ extortion performance rituals.

The Ragyabpas lived in a suburb outside the Lingkor called appropriately enough Rako Lingka, or “park of horns”. One of the earliest Western visitors to Lhasa (Abbe Huc) has described the unique architecture of this area: “In the faubourgs there is a quarter where the houses are built entirely with horns of oxen and sheep. These curious buildings are extremely solid, and present a rather pleasing aspect … these strange building materials lend themselves marvelously well to endless combinations, and form the walls designs of infinite variety. The spaces between the horns are filled with mortar. These houses are the only ones which are not whitewashed.”[21]

According to Charles Bell the Ragyabpa make a very good living. They also have a definite connection with the criminal elements of Lhasa since they were in charge of criminals who had just been released from jail and had nowhere to go. The Ragyabpa guild served as a kind of half-way house. Criminals released from prison were put in shackles and allowed to beg. Before the 13th Dalai Lama abolished capital punishment in circa 1896 and banned cruel punishments, it seems the Ragyapa also had the gruesome task of carrying out such punishments.

Another begging fraternity connected with the Ragyabpa were the Peendunga, whose women-folk were capable of unleashing a very loud and unpleasant wailing if you didn’t pay them fast enough. Other professional beggars in Lhasa were the fiddlers (tse-tse tangyen), beggars with performing monkeys (trangbo-tre-tse), and wandering acrobatic dance troupes (khampa repa) who were not only skilled tumblers, drummers and dancers but claimed a spiritual connection to Milarepa.

Opera performers were not considered beggars though it was required of families who sponsored shows to give them presents of money, grain and chang. But I am told that there was one virtuoso beggar (michik-lhamo) in old Lhasa who could put on a full opera performance all by himself. These motley panhandlers and entertainers sang, danced, recited, joked and performed for the entertainment and the largesse of the good people of Lhasa.

The most well known of such mendicant entertainers, indeed almost an institution in himself, is the Drekar Sampe Thondup “White Seeds Fulfiller of Wishes”[22] who always showed up on New Year’s Day, weddings and other important occasions. The Drekar recited auspicious verses “… in a stream of extravagant language, interlarded with jests which cannot be said to border on the vulgar, for they are well across the line.”[23] One section of the Drekar’s monologue is the “Origin Chronicles of Tibet” (bhod sepa chagpae chag-rap) where short pithy verses describe the major cities, towns, and religious sites of Tibet and recount their (largely) fabulous origins.

Besides the extortionists and the entertainers you had an altogether different and more honored class of mendicants, who were essentially religious practitioners. Begging in general was not, of course, considered a respectable occupation in Tibet, but probably in no other society in the world was begging less looked down on. Buddhism has a long tradition of monks and nuns begging for alms (so-nyom) as the Buddha himself did. So you had pilgrims from Kham, Amdo and elsewhere travelling to Lhasa and Central Tibet, and making their journey entirely through begging, in order to increase the merit of their pilgrimage. Many of the pilgrims were well off and did not need to beg, but chose to so for spiritual reasons. One of the leading chieftains of Lithang, Pon Sogyal (father of the famous resistance leader, Yunru Pon) travelled to Lhasa as a beggar, as did a friend of mine Nyarong Aten whose biography I wrote in 1979.[24]

So in Lhasa, especially during the Monlam (Great Prayer) Festival and also during the Saga Dawa festival commemorating the Enlightenment of the Lord Buddha, the sides of the Lingkor (Outer Circuit) road were jammed with a variety of mendicant as the Lama Mane, who recited the lives of saints using thangkas as visual aid. The Tashi Gomang did much the same but with elaborate miniature temples behind whose many doors and windows were tiny statuettes of saints and deities. The Deylok Shayngen told the stories of spiritually accomplished people who we might these days describe as having had “near death experiences”. Then there were the Chanze Lama, pilgrims who had prostrated all the way to the Holy City from many hundreds of miles away, and a host of other mendicants to whom the good citizens of Lhasa would distribute money and food.

That still left you with a large section of the beggar population, discussed earlier, from whom a spiritual motivation had probably not been crucial in the selection of their particular way of life. There were all sorts of reasons why people chose vagrancy: crop failure, inability to pay debts, desertion from the army (or from a monastery), family problems and so on. For some it was just a way of “dropping out”. I heard of someone nicknamed Tingsha[25] possibly of aristocratic descent, joining a band of beggars and going around Lhasa playing the tse-tse fiddle and getting drunk.

Heinrich Harrer, with his Teutonic sensibilities, says that Lhasa beggars were just lazy. Unfortunately, he wasn’t just airing an opinion here, but speaking from hard experience. When he was commissioned to build his famous dam the government rounded up seven hundred sturdy beggars as laborers. Although they received good food and pay they were all absent in a few days. “It is not lack of work or dire necessity that makes these people beggars, nor, in most cases, bodily infirmity. It is pure laziness. Begging offers a good livelihood in Tibet and no one turns a beggar from the door.”[26] Harrer goes on to observe “the produce of two hours ‘work’ (Harrer is being sarcastic here) keeps him going for the day.”

The historian Shakabpa says pretty much the same though he is less exact about the time. “Even the beggars of Lhasa have only to ply their trade for some time in the morning to get enough food for the day. In the evenings they are all nicely drunk.”[27]

On the question of how the beggars got “nicely drunk” it might be noted that they drank the best chang in all of Lhasa. I am not making this up.[28] All the changkang taverns and most families in Lhasa brewed their own chang. The Tibetan government did not tax the production or consumption of alcohol. Big families even had their own in-house expert brewer, usually an older woman respectfully called Ama chang-ma. Whenever a batch was ready the initial “offering” (changphud) was poured into a clean pitcher and the daughter of the house or a maid, always dressed in her best, would take the pitcher to the Pela-chog, the chapel of the goddess Palden Lhamo (Sridevi) at the south-eastern corner of the Jokhang roof. The sacristan at the temple would pour it out into a giant vat by the side. In the evening the beggars of Lhasa would line up by a side-door and the sacristan would let each one have a full jug of this pure and consecrated ale for the token payment of a chek-ke coin, the equivalent of a penny.

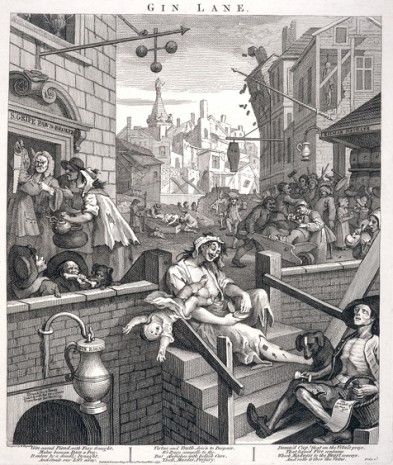

I am not trying to suggest that the life of the average Lhasa beggar was, for all the free beer, in any way a bed of roses. Of course it wasn’t. Tibet was admittedly a politically backward and industrially undeveloped society, but the account of Lhasa beggars drinking beer that was at least clean and wholesome made me think of Gustave Doré’s engravings of the squalor and despair of working class London, and Hogarth’s famous print of Gin Lane (in the notorious slum parish of St. Giles) where the working poor destroyed themselves and their children by drinking manufactured spirits (frequently mixed with turpentine), foisted on them by a government whose primary concern was raising revenue from alcohol sale. I wrote about something much the same happening in Lhasa from the early 1980s onwards, “a ubiquitous alcoholism fuelled by the sale of cheap Chinese rot-gut, baijiu and sanjiu … pushing Tibetans into immediate unemployment and ultimate extinction.” [29]

I am not the first one to make such an observation contrasting Tibet and Britain of the Industrial Revolution. Hugh Richardson, Britain’s last representative in Lhasa and foremost Tibet scholar of his time, in writing about old Tibet, reflected:

From fourteen years’ acquaintance with it I maintain that it was not deliberately cruel or oppressive. It did not need force to maintain itself … It had evolved a closely knit society with a balanced economy and higher standard of living with far less distance between rich and poor than obtained, say in India (and also say in China. JN). There was a regular surplus of grain, and large reserve stocks. No one suffered the degrading conditions of life of which we read in the industrial revolution here or in Ireland.[30]

________

To return to our story of the Lhasa Ripper, Rinzin and Damdul were released in late 1934, probably after the arrest of the real serial murderer. Both men had suffered much in prison. My primary informant remembers that her uncle Bhu Damdul was very resentful of the Tibetan government especially the Lhasa aristocracy, and with good reason. He died destitute.

But an element of poetic justice developed in this case. When Damdul and Rinzin were in prison, Tsepon Lungshar was arrested in May 1934 for plotting a coup d’état against the Tibetan government. He was put in the same prison as the two men he had framed and was still there when the two were released later that same year. Although the 13th Dalai Lama had abolished capital punishment at the turn of the century and banned all “cruel and unusual” punishment, Lungshar suffered the dreadful punishment of being blinded. Goldstein tells us “The mutilation was terribly bungled” by the Ragyapa men, as this punishment “had not been exacted for such a long time that there was no one who had ever seen it done.”[31]

Subsequently, Lungshar was incarcerated at the Shachenjok prison in Zhol below the Potala. Lhalu Lhacham did everything she could to free him. My mother remembered the lady calling at Tethong House a year or so after my grandfather Gyurme Gyatso returned to Lhasa from his duties in Kham (as governor-general) and joined the kashag as a full-fledged minister. When my mother showed Lhalu Lhacham into the living room she immediately did a full prostration (kyang-chag) before a horrified Gyurme Gyatso who hurriedly helped her up. My mother remembered the loud thump of her ample figure dropping on the wooden floor. The lady then burst into tears and appealed for the release of Lungshar. “What can he do now? He is just blind and helpless.” It would be an act of compassion (gyewa) to release him.” Most probably Lhalu Lhacham appealed to others in the kashag, for Lungshar was soon released. He lived out the rest of his life quietly with Lady Lhalu. He died in 1939. His son Tsewang Dorje was adopted by Lhalu Lhacham into the Lhalu family, and reinstated as a government official and later became a cabinet minister and the governor-general of Eastern Tibet (do-chi) in 1947.

As for our Lhasa Ripper, aka Chonze Serso Chenba, the Nepalese national with the gold-capped teeth, I have been unable to dig up anything further on him following his arrest and presumed incarceration.

For all the stories, facts and scraps of information I obtained and accumulated over the years for this essay I am indebted to my mother Lodi Lhawang, my uncle Tethong Sonam Tomjor, grandaunt Tesur Yangchen Palmo, uncle Rakra Rinpoche, uncle Tethong Tsewang Chogyal, Nyemo Bhonshod Bhusang, TIPA director Chitiling Ngawang Dhakpa, Music instructor Gyen Lutsa, Opera Master Gyen Norbu Tsering, former State Astrologer Drakton Jampa Gyaltsen, uncle Nornang Ganden la, my mother-in-law Tashi Dolma la (Mrs. Lhamo Tsering), Italian scholar Roberto Vitali and my primary informant for the “Ripper” story, Mrs. Kalsang Chukie Tethong. I must also thank Tashi Tsering la, director of the Amnye Machen Institute for many snippets of information and much sound advice. To the authors of all the articles and books cited in the Reference Notes from which I gleaned further facts and figures, my thanks.

REFERENCE NOTES:

[1] Most Tibetans call this instrument by its Chinese name, yangchin (揚 琴) meaning “foreign instrument”, since it was originally an ancient Persian instrument which probably came to China in late Manchu times. You can find versions of it in Eastern Europe and even in American Appalachia. In India it is known as the santur, and Pandit Shivkumar Sharma of Kashmir is credited with making it a popular classical instrument. Some Tibetans incorrectly call it gyumang, “many strings” which is an old synonym for dranyen. Quite a few Chinese musical instruments as the suona (Central Asia) and the sheng (South-east Asia) are imports. For instance the two string fiddle, the Huqin (胡琴) or “Mongol (or Tartar) instrument” which Tibetans also play and call piwang or tse-tse, came to China during the Yuan dynasty.

[2] B. J. Gould, The Jewel in the Lotus, Chatto & Windus, London, 1957. P.236

[3] Jamyang Norbu, “From Darkness to Dawn: Legal Punishment in Tibet from Imperial Chinese Rule to Independence” Shadow Tibet, https://www.jamyangnorbu.com/blog/2009/05/17/from-darkness-to-dawn/

[4] Nicholas and Deki Rhodes, A Man of the Frontier: S.W. Laden La –1876-1936, Rachna Books, Kolkata, 2006, p38-45.

[5] Purshottom Mehra, The North-Eastern Frontier: A Documentary Study of the Internecine Rivalry between India, Tibet and China, OUP, Delhi, (1979) Vol.2 p.37/8.

[6] Interview with Lhasa police physician, Nyemo Bhusang, on 9th September 1991, at McLeod Ganj, Dharamshala, India.

[7] Ibid. Bhusang interview.

[8] I am grateful to my friend the Italian scholar Roberto Vitali for this nugget of historical information.

[9] This is a summary of a story told to me by my mother, Lodi Lhawang. I hope to publish the full account, along with other such stories, one of these days.

[10] K. Dhondup, The Water-Bird and Other Years- A History of the 13th Dalai Lama and After, Rangwang Publisher, N.Delhi 1986, p77.

[11] Tsepon W.D. Shakabpa, One Hundred Thousand Moons: An Advanced Political History of Tibet, Vol.2. trans. Derek F Maher, Brill, Leiden & Boston, 2010. p. 813.

[12] H. E. Richardson, Tibet and Its History, Oxford University Press, London, 1962. p.133.

[13] Charles Bell, Tibet Past and Present, Oxford, 1924 p 204.

[14] Thubten Jigme Norbu & Colin Turnbull, Tibet, Chatto & Windus, London 1969, p.41.

[15] Ibid. Vitali.

[16] The poem was published by Gergen Tharchin at Kalimpong in 1936 at the Tibet Mirror Press as Memories of Lhasa. Composed by H.E. Shelkarlingpa at Darjeeling in 1910,11.

[17] Isabelle Henrion Dourcy, “Women in the Performing Arts”, in Women in Tibet, (eds Janet Gyatso/Hanna Havnevik), Hurst, London, 2005, p.204-207.

[18] Hisao Kimura, Japanese Agent in Tibet, Serendia, London, 1990 p202-03.

[19] Sarat Chandra Das, Journey to Lhasa and Central Tibet, John Murray, London,1902, p164

[21] Evariste Régis Huc. Souvenirs d’un voyage dans la Tartarie, le Thibet, et la Chine pendant les années 1844, 1845 et 1846 (Paris : Librairie d’Adrien le Clerc 1850) Vol II p. 254.

[22] Charles Bell and others refer to this beggar as the “White Devil” (hdrae-dkar). Rakra Rimpoche told me that the true auspicious meaning of the name was “White Seed” (hbrae-dkar), both pronounced the same.

[23] Charles Bell, The People of Tibet, Oxford 1928, p.275

[24] Jamyang Norbu, Warriors of Tibet, Wisdom Publications, London, 1986.

[25] Conversation with T.C. Tethong in November 2012.

[26] Hienrich Harrer, Seven Years in Tibet, Dutton, New York, 1954, p. 257

[27] Tsepon W.D. Shakabpa, An Advanced Political History of Tibet (Bod kyi srid don rgyal rabs), Shakabpa House, Kalimpong, 1976. (My translation)

[28] My grandaunt Tesur Yangchen Palmo once teased me about the occasional bottle of rum I received from kushog Lobsang Tsering la, the late caretaker of the Palden Lhamo chapel at the Tsuklagkhang in Dharamshala. He was a great opera fan and a friend of mine. She then told about the special provenance of alcohol products coming from this particular chapel.

[29] Jamyang Norbu, “Lhasa Eternal City (2)” Shadow Tibet, https://www.jamyangnorbu.com/blog/2013/06/01/lhasa-eternal-city-2/

[30] Hugh Richardson, “Tibet Past and Present”, High Peaks Pure Earth: Collected Writings on Tibetan History and Culture, Serendia, London, 1998. p. 704

[31] Melvyn C. Goldstein, A History of Modern Tibet 1913-1951: The Demise of the Lamaist State, University of California Press, Berkeley, 1989, p. 209.

Ah, my kind of Tibet, what a merry bawdy play! So I am going to assume all the Agu Tenpa stories I ever heard were true.

More than a bit of Dostoevsky there. Fascinating read. The dark side of human animal is formidable indeed to say the least; you can appreciate why evolution would select such traits for survival.

This calls to mind a favorite poem of mine, the first verse of, An Essay on Man, by alexander pope.

Know then thyself, presume not God to scan;

The proper study of mankind is Man.

Placed on this isthmus of a middle state,

A being darkly wise and rudely great:

With too much knowledge for the Sceptic side, With too much weakness for the Stoic’s pride,

He hangs between; in doubt to act or rest, In doubt to deem himself a God or Beast,

In doubt his mind or body to prefer; Born but to die, and reasoning but to err;

Alike in ignorance, his reason such Whether he thinks too little or too much:

Chaos of thought and passion, all confused;

Still by himself abused, or disabused;

Created half to rise and half to fall; Great lord of all things, yet a prey to all;

Sole judge of truth, in endless error hurled: The glory, jest, and riddle of the world!

Blaise Pascal through a glass darkly…

What a chimera then is man.

What a novelty! What a monster, what a chaos, what a contradiction, what a prodigy.

Judge of all things, imbecile worm of the earth; depositary of truth, a sink of uncertainty and error: the pride and refuse of the universe.

Jamyang, I have to thank you for this fascinating and engaging piece which you wrote for the festschrift that Robi Vitali edited. It was indeed diverting and entertaining. But it also taught me more than a few things of which I was quite ignorant. I never tire of hearing the information, anecdotes and stories of old Tibet and old Lhasa that you’ve gleaned from so many members of your family, old acquaintances and friends over the years. You not only have the stories, you tell them well–as only a writer of talent could. I fear for what is being lost and will be lost as the years go by and only a fraction of this information is set down. I’m honored by your contribution to the volume but more so by your friendship over so many years. Now I really do wonder about the fate of Chonze Serso Chenpa. Perhaps he was released in the aftermath of 1951 (or the chaos of 1959)? Perhaps he found a career as a ‘khyug khyi (presenting himself as a mi ser victimized and tortured by the upper strata)? Enquiring minds want know?

Enquiring minds want know!

A pure treasure of a read.

Jamyang La, you made my day again. What a pleasure to read. Thank you for once again giving me a ride in your time-machine and showing me the old Lhasa.

Dear Guen la

Thank you for your most informative and entertaining article. I thoroughly enoyed it..

Regarding the photo of the tashigomang in bhutan, I just want to inform you that the people are called “lam manip” in Bhutan and are not monks as such but “lay-practitioners”. There are usually married and do not wear the monks’ robes.

Once again, thank you

best wishes from spring in Thimphu

Jamyang la, thank you once again for these wonderful well researched mini documentaries of Lhasa. It is reassuring to know that Tibet and Lhasa city survived like any other metropolitan in the west; with its scheming and politicking and not full of praying monks and nuns. There is a lesson here for the Chinese communist to learn: While China still practices the death penalty for most crimes, Tibet abolished the death penalty in 19th century. That not all surfs were in bondage and leg-irons and starving as they claim.

Dear Jamyang-la,

What a lively reconstruction of Lhasa city/street history. So much room for an extended research on real life stories of Tibetan people/society just in and around Lhasa city of those days. I enjoyed it thoroughly. An amazing laudable contribution to Tibet’s history. A collection of at least a dozen of classic jargons in the history of profession/occupation of our society can be found clearly explained. Hope more will come up soon. Eagerly waiting Jamyang-la!.

Thuk-Je Che. sKu-Tshe-Ring!

Tsepak Rigzin

Jamyang Norbula – You are a story teller and a Very

GOOD one.What a wonderful way to honour your friend & scholar Professor Eliot Sperling.

I detect fine humour too – must be the cup of elaichi CHAI

Did any those Lhasan chivalries follow into exile? Isn’t Lhasa know for this not so famous saying: In Lhasa, while beggars sold the stomachs, the upper-class ladies sold their vagina.

Talking of social vices, Dharamsala is also famous of holding annual beauty contests. We all know that one of the early Zangmas was personally brought to VOA by its Tibetan service director. Know what, my sources claim that she is being hijacked by RFA’s Kalen Lodo with blessing is his savior Libby Lu. Surprised, I challenged my source about its veracity. I was surprised to be told that she has a disposable boy friend of sort. Interesting! Can’t wait to see the unfolding of the any secret deal. What out folks!

Talking of Free Asia, why is Free Asia Radio not covering Gyalwa Karmapa program?

Is it the same guy mentioned above in Free Asia that is stopping the coverage of Gyalwa Karmapa? May be it is time we the followers of Gyalwa Karmapa should write about this censorship to Chairman of House Foreign Relations. Insiders are saying that is the most effective thing to pressure on these rotten people.

Tibetan media should give equal coverage to all sects not just Geluk.

As a reader and a learner, i thank you so very much for this entertaining yet informative and most importantly beautiful piece of tour. Thuk Je chee….

Speaking of dubious characters…

I havn’t read anything on the guy, I know of him only through gossip. And if the gossips are half right, Kundun’s brother Gyalo Thondup seem to be a real shady character and a bit of an asshole, not unlike his dad maybe. He’s got a book out now, much anticipated I hard, The Noodle Maker of Kalimpong. Maybe the book will finally reveal what happened to all that gold and silver brought out from Tibet by a caravan of mules. Or some gossips will have you believe…..

Here is an article on the gold and silver .. all gone, in bad investments? I actually suspect all that gold is hidden in plain sight adorning temple roofs…lol

https://sites.google.com/site/tibetanpoliticalreview/articles/afactualaccountofthetibetangovernmentsgoldandsilver

What else was hidden from the masses.kudrak apeyro

This is a sensational article. I wish it had gone on for about twenty more pages. Please comment on the picture of three Lhasa women, which you labeled “Nonzin la, a celebrated Lhasa beauty of the forties, with friends.” The three women were identified for me by George Tsarong as left to right: his wife, Yangchen Dolkar Ragashar Tsarong, Sonam Topgyal & Kate Tsarong Shatra (George’s sister). It was taken in 1947. Who was Sonam Topgyal & why did you call her Nonzin la?

My other question is about the poem “How many silver coins do I have to spend for you? / Even if the Sakya princess gave me a better deal / I don’t want her.” Does this refer to Dagmola, the Sakya Princess from the Land of Snows, who is now in Seattle? Does it mean that she was a great beauty or something not so nice?

Lynn, Nonzin la later became the wife of

Yaba Sonam Topgyal (of Sikkim) who started a Dharma center in New York City. She had earlier married a rich Chinese merchant in Lhasa in the late forties who took her to Beijing. En route at Sining she was carried off by the warlord Ma Bufang (or one of his generals) who was captivated by her beauty – or so the story goes. She lived an interesting life. I met her in New York in 1975.

I don’t think the Sakya Princess mentioned in the verse was the Dagmo. In the verse she is referred to as “jetsun kushog”, which is a polite way of addressing a high-class nun. So probably the nun was a daughter of the royal Sakya family, with a reputation, deserved or not. If I come across her name I will let you know.

Because Norzin la is in a picture with other Tsarong women, I thought maybe she was a Tsarong. Who were her parents?

Also, is Yaba a title? Does Sonam Topgyal have a last name?

I don’t know much about her parents but the title Yaba is a Sikkimese one denoting the person is a member of the Sikkimese aristocracy.

I have always seen this spelled as Yap and heard it defined as “Sir”. Thanks for the information.

My mother mentioned a jhakpa named Jha-go (vulture) Topden who she thinks must be from Dege. She told me that in old days people used to warn travelers of Jha-go Topden. She also mentioned that there used be some popular Drukpa jhakpas around Phari and Dromo. Then there’s the rumour of counterfeit Sang (Tibetan paper notes) coming from Gangtok.

Kas,

No matter what your mother told you or the stories that you believe let me tell you that it won’t effect one bit the Jagotsang family. The ignorants have always been saying such things. Its nothing new that the family doesn’t know and they don’t care to explain anything. It just betrays the serf like mentality of those ignorants, thats all i can say. They know what they’re about. Its obvious.

By the way, i don’t know where your roots are from but our ancient culture like many other consider the Vulture to be a powerful totem and also the Vulture is considered a great purifier. What would you know?

SONAMTSO,

Sorry if my comment offend you in any way. But to be clear, in my comment I only mentioned a jhakpa who’s popularly known as Jha-go(nickname, not a family name) Topden. Nowhere in my comment I’ve mentioned Jagotsang (from Dege?) Even during 90s in Lhasa, there’re popular street characters with nicknames like Jha-go, Dok-khyi etc.

Since you are curious, I’m also a Tibetan and I know very well about our culture. After death, we offer our dead bodies to the vultures as a generous act (དགེ་བ་གཏོང་བ་) of disposing our lifeless body.

When Jagotsang family was escaping Tibet into exile they were surprised & Highly AmusedD coming across many villages in the border area -Tibetans who told them they had encountered several jakpa groups Claiming to be under Jago Tobden of Jagotsang Dege over the years – but now here was the True Jago clan.

Thats how some Jakpa groups survived & operated .

Son am Tso I agree with what you said especially latter part.

Thamzing; cultural revolution here we goooo….

Its clear that you don’t know nothing. At least you should have done some research instead of following some Lhasa Barkhor gossip.

Now because the family was very powerful at the time – much loved and respected by their own clansmen and feared by some. Obviously there’s bound to be people who use the name for their own personal gain and power flaunting. I am aware of a certain individual who is guilty of that and did some real nasty things in a particular region of Tibet. That was very wrong. But if we are going to talk about all the wrongs of the past, then you know there’s lots that one can talk about. The seemingly cultured but the old beliefs and prejudices of those days would be something one can start with.

“After death, we offer our bodies to the vultures as a generous act of disposing our lifeless bodies”

No! You still don’t get it! Don’t be a self righteous fool to believe that you are being generous by offering your dead body to the vulture. It is the sacred Vulture that is doing nature’s service of purifying our earth.

My post @ 27 is response to KAS @ 25

SONAMTSO,

Why can’t we talk about the past wrongs? Though my intention wasn’t to dig our past wrongs. I was just providing an anecdote regarding jhak-pa. Somehow it seems my comment hurt your personal/family/clan pride.

Regarding the vulture topic, yes I accept your point that the vultures in a way helps purify our earth. But whether sacred or not, you should know that the vultures (Griffon Vulture to be specific of those in Tibet) are scavengers, which means they don’t kill to feed. Instead they feed on carcasses hunted by others. So in our sky-burial tradition we offer the dead bodies to them as their source of meal. Whether I’m a “self-righteous fool” or not, the idea of offering one’s dead body to earn religious merit is one of the beliefs beside other reasons. If there’s no one offering it to the vultures, there’s no sky-burial.

And one more thing. You can regard me as someone who “don’t know nothing” but hope you are aware of the Tibetan saying “སྐྱུང་ཀས་སྐྱུང་ཀ་ཟེར་རེས་མ་བྱེད།མཆུ་ཏོ་དམར་པོ་འདྲ་འདྲ་རེད།”

Tashi Delek!

KAS

“Why can’t we talk about the past wrongs”

We MUST talk about the past wrongs. Its very important do so that we may never commit the mistakes of the past, correct our ignorant prejudices of the past, to become more open minded, learn how and where all the age old problems stem from. I am all for it. Just don’t be fixated on a certain family name and fame.

” So in our sky-burial tradition we offer the dead bodies to them as their source of meal”

Just to let you know- Existence is not human-centric. If tomorrow we humans were to vanish from this earth, other species will do just fine.

Final TASHI-DELEK!

SONAMTSO,

Haha…neither I said our dead bodies are the only’source’ of meal for the vultures. That’s lame! Anyway, Tashi Delek.

In Tibetan Buddhist culture Vulture is considered SACRED.

Vulture stands for cleansing & purification.

Vulture is also considered “sky dancer” – DAKINI.

Vulture symbolizes endurance of the greatest kind & so on so forth.

Tashi Delek!

For what’s it worth: Assuming the Vulture as a name for what it symbolises is one thing.

Being a literalist about it is well- plain ignorance.

Just like a Total newbie to the Tibetan Buddhist culture on seeing one of the more awesome (wrathful) thanka painting.

And in here people are fighting over vultures.

@WHAT DREAMS MAY COME, there’s a difference between fighting and having a proper debate. But I know it’s bit naive regarding more serious discussions, so we already put an end there. 🙂

KAS

“Even during 90’s in Lhasa, theres popular street characters with nicknames like Jha-go, Dok-Khyi etc.”

I can imagine because my uncle visited Lhasa on a pilgrimage in the 80’s. He said that he was eating in a restaurant with an elderly relative when out of nowhere and for no reason this one man starts passing rude comments about Khampas and not just that started saying some derogatory things about HH 16th. This of course triggered my elderly relative much but he had to hold it because of the fear of consequences and knowing gyami sowas lurking all around. So, I don’t doubt you at all on that.