HISTORICAL ACCOUNT OF TIBET’S ARMED STRUGGLE AGAINST COMMUNIST CHINA’S MILITARY OCCUPATION & TYRANNY

On November 8th last year the Dalai Lama received a presentation set of eight books that constitute as complete a history of Tibet’s heroic resistance to Communist China’s military occupation and tyranny as exists to this day. This impressive body of work was put together by the late Tsongkha Lhamo Tsering, exile Tibet’s intelligence chief and head of operations of the Mustang Resistance Force. He was also minister of security in the exile-government from 1996. From what I understand His Holiness graciously took time from a particularly hectic schedule that day to receive the books from Mrs. Tashi Dolma, the widow of the late Lhamo Tsering, and also his daughter, Diki Thondup and son Tenzin Sonam.

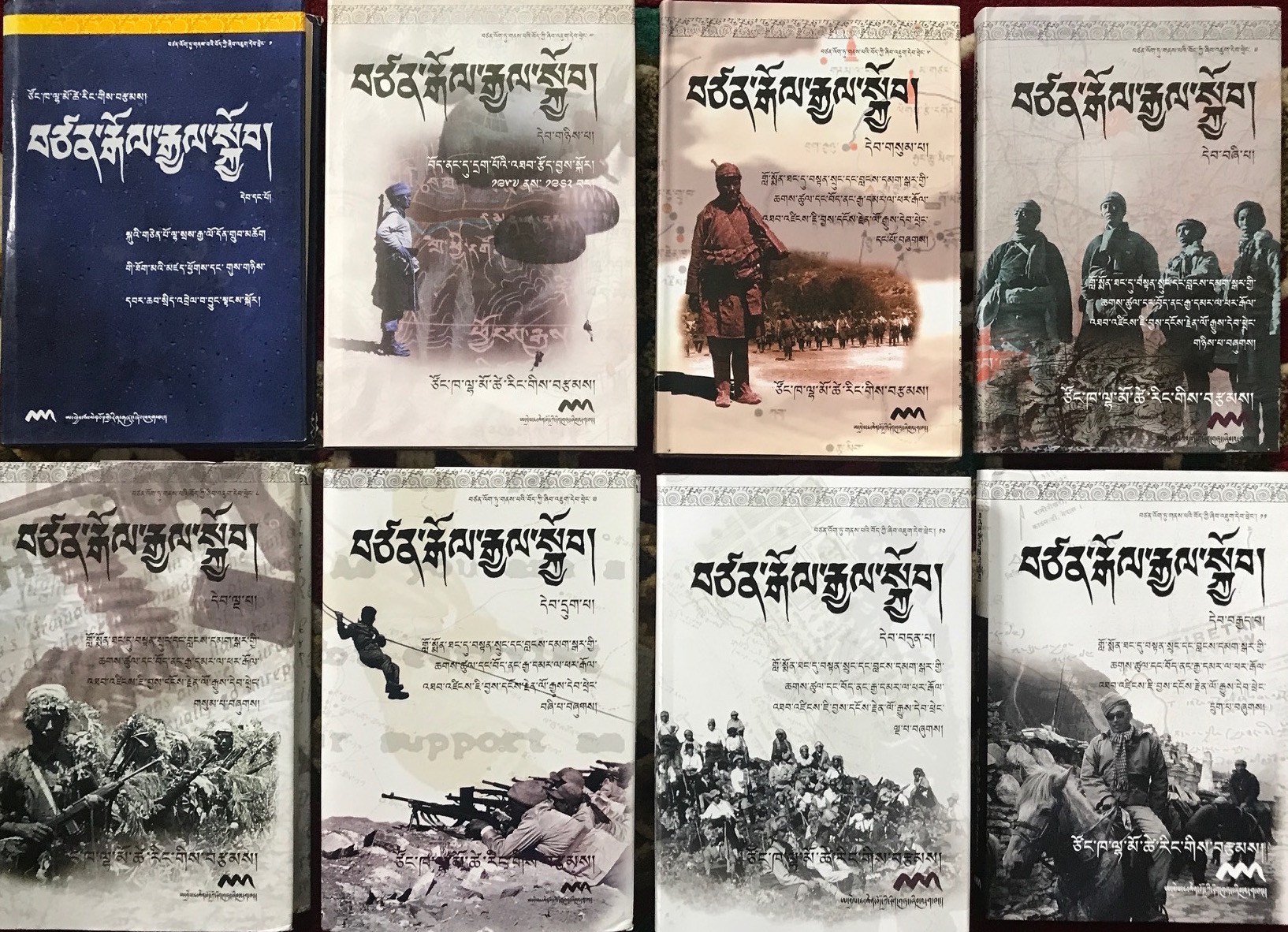

The series of eight volumes is titled btsen-rgol rgyal-skyop in Tibetan and translated simply as RESISTANCE in English. The series were published by the Amnye Machen Institute (AMI) under its Occupied Tibet Studies program and edited by the great scholar, Tashi Tsering la, AMI’s director and founder. The printing of a number of the volumes was sponsored by Lodrik Welfare Fund, Pokhara.

Volume one deals with Lhamo Tsering’s own family background in Amdo, his meeting in Nanjing with Gyalo Thondup, the Dalai Lama’s older brother, and their work together with Tsepon Shakabpa and other expat Tibetan officials in Kalimpong to create a secret anti-Chinese organization.

Volume two recounts the first contact with the CIA and the training of Tibetan fighters in Saipan and Colorado. It also discusses Gonpo Tashi Andrugtsang’s founding of the Chushigangdruk in Lhoka, and provides a detailed account of CIA airdrops inside Tibet, including the eight special para-drop missions into Tibet from 1957 to 1962.

Volume three gives a detailed account of the establishment of the guerilla force In Mustang, and the enormous problems– lack of weapons, supplies, etc. – that it encountered and eventually overcame.

Volume four recounts the many guerilla raids conducted into occupied Tibet by the Mustang force, particularly the raid where an “intelligence goldmine” of Chinese political and military documents was captured.

Volume five deals with the formation of the secret “Co-ordination Office” of CIA, Indian Intelligence (RAW) and Tibetan intelligence officers, and its organization. It also describes the many intelligence networks that were set up inside occupied Tibet and the constant ‘cat and mouse’ struggle against Chinese counterintelligence.

Volume six relates the administrative crisis in the Mustang leadership in 1970 and the recall of commander, Gyen Yeshi Kalsang. It also describes the special training and educational programs that were initiated in this period and the end of American support.

Volume seven describes the resettlement programs that were started for retired fighters and also the problems the force faced with the Nepal government. Also recounted is the arrest of Lhamo Tsering by Nepalese police in Pokhara and the negotiations that took place between the Mustang Force and Nepalese authorities.

Volume eight gives an account of the Dalai Lama’s taped message to the Mustang fighters calling for their surrender and its tragic aftermath. It also describes the flight of Commander Gyado Wangdu and his men, and Wangdu’s heroic death. The book concludes with a description of the continuing resettlement program of retired Mustang volunteers and their families in Nepal.

The enormous amount of information in these eight volumes, though invaluable, makes for challenging reading. Nonetheless I would encourage all Tibetans, even the most book averse, to buy them as they contain a large number of hitherto unseen photographs, not only of leaders but even individual agents and members of the many teams air-dropped into Tibet. Lhamo Tsering was a meticulous collector of documents and the books are replete with facsimiles of intelligence reports, maps, press-clipping, correspondences, etc., etc. He has even reproduced a copy of a letter I wrote to him shortly after I arrived at Mustang.

After he passed away in 1999 I wrote a eulogy that did not get much circulation then. I reproduce it here to give readers a feel for this intelligent, courageous, dedicated and incorruptible official – the kind of person that has become ever more difficult to find in the exile Tibetan world.

Silent Struggle

Tsongkha Lhamo Tsering (1924 -1999)

When I first arrived at the Resistance headquarters at Kalsang Phug in Mustang in early July 1971, I was a bit surprised to come across a library. Granted, it was not much of a library, it only had a few books and some Tibetan magazines like Sheja and Tibetan Freedom, but I had assumed I would be hunkering down in a rough bunker or a tent, stripping down my rifle to while away the time. So this was a pleasant surprise. The library was the brainchild of Lhamo Tsering. He had even designed the small building and laid out the flower-beds outside. The compound was surrounded by a wooden fence that also served as a backrest for the low benches where we sometimes sat in the evenings drinking black tea, admiring the plants and looking up at the disconcertingly close face of the giant Nilgiri range.

The Resistance journal, Ghotok (Understand) was another of Lhamo Tsering’s ideas. The editor was a sharp young fellow from Tsum called Damdul, whose snub nose and spiky hair bought to mind the Artful Dodger. My own contribution to the journal was picking up stories from the BBC World Service and sometimes doing a piece. The magazine was mimeographed, or, as the Tibetans called it, “oil printed” (num-par). The Gestetner machine would sit out in the blazing sun for an hour or two and when the rollers and works were nearly too hot to touch we would crank out the voice of the Resistance. The heat made the ink flow nice and even and we got perfect results every time. Lhamo Tsering had also set up a school for the younger soldiers of the Resistance. The headmaster was an ex-sergeant (shengoe) Thondup Gyalpo la, from the Guards regiment of the old Tibetan army, who kept the fairly wild young nomad and Khampa men on their toes. I gave classes in arithmetic, English and conversational Nepali. Occasionally I would hold forth on the various liberation movements that were shaking the world at that time, and which the men enjoyed hearing about.

One day in the library, I picked up an English translation of Sun Tzu’s Art of War, with an appendix of selections from Mao Zedong’s writings on guerilla warfare. The margins and borders of nearly every page were heavy with neat pencilled annotations in Chinese, English and Tibetan. I found it somehow reassuring that our chief of operations — for that was roughly Lhamo Tsering’s role in the organisation — was someone who, intellectually, worked at his job. He worked at it in other ways too. He would be up an hour earlier than anyone else and have finished his exercises and his morning run by the time everyone else turned out for PT – when he would join them for another round of exercises. He was a soft-spoken person and I never heard him raise his voice at anyone. He was polite to the point of formality with his officers and agents and even the common soldier.

Thinking back, I realise I owe Lhamo Tsering for the opportunity to join the Resistance. As a boy I had tried a couple of times and had failed. I once even got to meet Gyalo Thondup, the Dalai Lama’s older brother, who was the overall kingpin of the Resistance, but in an undefined eminence grise sort of way. I went to his Delhi apartment at Golf Links and begged him to let me join. But he laughed at my naiveté and packed me off home. A couple of years later I met Lhamo Tsering in Dharamshala. He accepted my services as a matter of course, and even commended me for my “simshuk” (patriotism). I didn’t know that Lhamo Tsering was at the time neck-deep in problems: with the withdrawal of American support for the Resistance and the abrupt departure of his boss Gyalo Thondup for Hong Kong. He probably didn’t need an additional headache in the form of an enthusiastic but totally unprepared rookie like me. I benefited from his thoughtfulness in other ways. He regularly sent me Time, Newsweek and other magazines through our courier. I was just a volunteer, like everyone else up at Mustang, but he must have felt that coming from a relatively privileged educational background, I was going to get bored in the mountains. I wrote to thank him and also described my positive impression of the camp and the whole set-up, in the letter. Years later, going through his papers, I was touched to see my old letter carefully filed away in a volume of documents of that period.

The men, without exception, had tremendous respect for him, more, I think, than for any other living Resistance leader, even the Dalai Lama’s brother. Of course, he had his detractors. Earlier a small breakaway faction of the Mustang group had left with the former commander, Baba Yeshe Kalsang, which split the whole “Four Rivers Six Ranges” organisation in the exile world. The faction that supported Yeshe, among other accusations, charged Lhamo Tsering with being Chinese. They based their accusation on the fact that members of the Dalai Lama’s family, when speaking among themselves in their native Sining dialect, called Lhamo Tsering by the Chinese name (Bei Xiansheng) he had been given when he first attended a Chinese school.

Lhamo Tsering was born in 1924 in the village of Sina Nagatsang near Kumbum Monastery in Amdo, then under the Chinese Muslim (Hui) warlord, Ma Pufang. Nagatsang was near to Taktser, the Dalai Lama’s birthplace. Chinese immigration had since Ming times asserted itself in those parts of Amdo, and Nagatsang had over fifty Chinese families to two Tibetan. Till the age of eight he was a monk at Kumbum monastery, when he began attending the local Chinese primary school in the nearby village of Rusar. On finishing primary, school he went to the Teacher’s Training School in Xining City and graduated from there.

The end of his schooling in Xining coincided with the Sino-Japanese war and he was briefly conscripted into the Youth Volunteer Force of the Nationalist Chinese Army. Before he saw action, the war came to an end. He then went to the Institute for Frontier Minorities in Nanjing to pursue further studies. There, in 1945, he met the Dalai Lama’s older brother, Gyalo Thondup, who had also come to study in Nanjing. Lhamo Tsering became Gyalo Thondup’s assistant and close companion.

In 1949, Communist forces were taking China’s major cities one by one. Lhamo Tsering and Gyalo Thondup escaped from Nanjing to Shanghai. Gyalo Thondup then departed for Hong Kong and left Lhamo Tsering behind to collect a bank transfer. But the money didn’t arrive on time, and Communist troops surrounded Shanghai. Lhamo Tsering once told me of his experiences at that time. His vivid description of the period stirred in me boyhood memories of poring over photographs (probably Cartier Bresson’s) in an old Life magazine, of Shanghai’s last days: panic-stricken Chinese men in double-breasted suits or traditional long gowns topped with fedoras, women in Anna May Wong cheong-sams and cloche hats desperately pushing and shoving everyone else to get to the closed door of a Shanghai bank; bedraggled Guomindang officers and their mountains of possessions alongside other desperate refugees at the railway station, waiting for a train that would probably never come; and of course the inevitable abandoned baby by the tracks. Lhamo Tsering narrowly managed to escape Shanghai before the city fell. He and another Tibetan forced a local fisherman to row them out beyond the harbour to the open sea where a last ship bound for Hong Kong picked them up.

Lhamo Tsering settled in Kalimpong, the Indian frontier town and centre for the wool trade with Tibet. In February 1952, he accompanied Gyalo Thondup to Lhasa. This was Lhamo Tsering’s first trip to the Tibetan capital. Here he was able to observe and experience first-hand the implications of the Communist Chinese invasion of Tibet. After four months, Gyalo Thondup and Lhamo Tsering managed to leave Lhasa and returned to India. On the 6th of August, 1954, Gyalo Thondup, along with Tsipon W.D. Shakabpa and Jamyangkyil Khenchung, founded the Tibetan Welfare Association in Kalimpong. Lhamo Tsering was its main administrator. The objectives of the Tibetan Welfare Association were to oppose the Chinese occupation, to publicise internationally the Tibetan situation, and to initiate underground movements inside their homeland.

In 1956, the CIA decided to help the Tibetan Resistance movement. Their main contact was Gyalo Thondup. In July 1958, Lhamo Tsering secretly led a group of eleven Tibetans to America. They were trained first at a secret camp in Virginia, and then at the newly reactivated Camp Hale in Colorado. Lhamo Tsering was also trained separately in Washington, DC in intelligence tradecraft. The Americans did not at first tell the Tibetans where they were being trained but Lhamo Tsering managed to find out. He told me in an interview in 1991 how he had done it: “We were not told where the camp was. It was not a very mountainous area but it was well forested…I managed to find out through helping out in the kitchen. Our supplies were purchased in the city and delivered to our cook every day, along with the bills and receipts. One day I took a quick peek at a receipt. Below the name of the store were the words, ‘Richmond, Va.’ We were in Virginia.”

Following his return to India in August 1959, Lhamo Tsering created and headed an office for intelligence operations in Darjeeling. Its main function was to liaise between the CIA and the various Resistance operations that were being launched from India and Nepal. These included radio teams that were being parachuted into Tibet; radio teams that went overland; and the Mustang Resistance Force that was started in Northern Nepal in mid-1960. The ailing leader of the “Four Rivers, Six Ranges” Force and the undisputed leader of the resistance movement, Gompo Tashi Andrugtsang (1905-64) was then convalescing in Darjeeling. He passed on to Lhamo Tsering the old battle standard of the “Four Rivers, Six Ranges”, first flown in June 1958 when they set up base at Driguthang in Lhoka district. The old man also gave Lhamo Tsering his own Browning automatic pistol and sixty rounds of ammunition. He also entrusted to him his personal seal, made when the desperate Tibetan Government at Lhuntse Dzong in March 1959 gave him a dzasak title and appointed him commander-in-chief of all Tibetan forces.

From 1964 to 1974, the activities of the Darjeeling office were expanded and a tripartite office was created which had its base in New Delhi. Lhamo Tsering headed the Tibetan section of this office. The main operations of this office included the Mustang Resistance Force and the intelligence gathering missions inside Tibet. With a new era of Sino-American relationship heralded by Nixon’s visit to China, the CIA terminated their support of the Resistance in 1969. The Chinese began to put pressure on the Nepalese Government to do something about the Tibetan guerrillas in Nepal.

In 1974, Lhamo Tsering was arrested in Nepal and used as a bargaining chip by the Nepalese Government in its efforts to disarm the Mustang guerrillas. But he refused to co-operate and managed to send a message to the guerrillas to disregard his capture. Finally, the Dalai Lama sent a message to the guerrillas asking them to give up their weapons. Following the surrender of the guerrillas, Lhamo Tsering was imprisoned in Nepal for seven years. In Kathmandu Central Jail, Lhamo Tsering and six other Tibetans were housed together in one large cell. There was a real possibility of demoralisation, especially since they were left pretty much alone by the authorities and liquor was freely available through the prison Mafia. In the same interview, in 1991, he told me of his prison experiences:

“I told the others it would be difficult to survive if we didn’t organise ourselves. I suggested that we kept strictly to an active and productive routine every day without fail. The others agreed. I wrote down the routine and pinned it up on our cell wall. It went like this: We got up at six and then held a prayer service. After that we did exercises till eight when we had our breakfast. From nine we had classes in English, Hindi and Nepali. Teachers were no problem. The jail was crowded with lawyers and teachers from the banned Congress Party and other dissident political groups. In our jail there were more than one hundred such people. The previous Prime Minister of Nepal was in our jail for some time.[1]

After lunch we played volleyball till tea-time at three, after which you could do as you pleased. Little Tashi used to fly kites. He was from Lhasa and had a passion and the skill for the game. Ngagtruk and Pega were great chess players, and also very religious. They meditated a lot and both managed to recite the “Praises to Tara” over 100,000 times.

“The rest of us weren’t that spiritual. Our speciality was humour. Rakra was enormously funny and had an inexhaustible fund of hilarious stories and jokes. But Chatreng Gyurme was even better at making up strange tales. He made them all up in his head, and they were weird. Our jailers and the Nepalese prisoners were puzzled by the constant laughter that would come from our cell.

So we kept constantly busy and were never bored. In fact, I never seemed to have enough time for my own writing and reading. One of the books I did read at the time was Leon Uris’s Exodus. I was deeply impressed and moved by the courage and sacrifice of the Jews in their struggle to create an independent nation. We managed to keep up this routine till the day we left that jail — and we stayed healthy and mentally disciplined. The consequences of not doing so were only too clear in the Central Jail. There were many suicides.

“Our education programme was a great success. Everyone became quite proficient in Nepali and Hindi except for me. I sadly lacked the gift for languages. We shared our food and tea with our Nepali teachers. They did everything they could to help us, advising us on legal matters, drafting our petitions and helping prepare our defence. Since many of these lawyers and dissident politicians had friends in the various government offices, they even managed to get some documents concerning our case copied and smuggled into prison.

“One day, the jailed leader of the Nepalese Communist Party, Manmohan Adhikari[2] dropped by to talk to us. He had to apply for high level clearance from the Home Ministry for the visit, which surprisingly, they gave him. Adhikari told us he hadn’t come to discuss ideology or Communism, as we all had different views on this. He said that fundamentally we were all brothers in this world. He advised us that if we did no more than hope for clemency, we could be in jail for the rest of our lives. He suggested various ways in which we could try to advance our case and stressed that we were not to overlook even the slightest advantage or the most insignificant contact we had outside. He then went on to tell us not to pay too much attention to Nepali Government propaganda about “Khampa bandits” and “atrocities”. We were to remember that what we had done was for the sake of our country and people. In times of war unfortunate things did happen, but that was life, and we should not become disheartened. Before he left he said he had a personal request to make of us: that we keep in good spirits, good health and not lose hope.”

“We stuck to our routine till the last day of our jail term. We were released in December 1980.”

Lhamo Tsering was back in harness after a short seven-month break. Though his former work had been of vital national importance, his role had not exactly been a recognisedly official one, and he was generally known as “Yabshi Drunyik la” or Honourable Secretary (i.e. secretary to the Dalai Lama’s family). This time he worked directly in the Central Tibetan Administration (CTA) of the Dalai Lama. From 10th April, 1981 until 1st October, 1985, he was Additional General Secretary of the Department of Security (CTA). From 1986 until 1993, he was a member of the Advisory Board of the Department of Security (CTA). From 9th August, 1993 until 3rd June, 1996, he was elected Minister of the Department Of Security.

I am not privy to Tibetan Government intelligence secrets, and Lhamo Tsering’s activities of this period will most likely remain classified for years to come, but he was probably again running agents inside Tibet. I got a hint of this from a newcomer from Tibet whom I had befriended and taught English to at Bir school. This young Khampa, whom I suspected had been recruited, always spoke of Lhamo Tsering with respect bordering on awe. There was a general feeling among those who knew him closely that Lhamo Tsering was never quite the same person after coming out of prison, but it was nice to see that he could still inspire the kind of loyalty in his agents as before.

After his release, Lhamo Tsering also started work on a detailed history of the Resistance efforts that he had been intimately involved in. The entire eight-volume series, entitled Resistance, is being published by Amnye Machen Institute, Dharamshala. The first volume, The Early Political Activities of Gyalo Thondup, Older Brother of HH the Dalai Lama and the Beginnings of My Political Involvement, 1945-1959, was published in 1992. The second volume, The Secret Operations into Tibet: 1957-1962, was published in 1998.

Future volumes will include a five-part account of the Mustang Resistance Force; a two-part account of underground organisations inside Tibet; a four-part account of the underground organisations and intelligence-monitoring units set up inside Tibet; and finally, an account of the resettlement programme of the former guerrillas of the Mustang Resistance Force. These books cover the entire period from 1945 to 1988. All the volumes have already been written, and are being edited by the director of AMI, Tashi Tsering.

After a long illness, Lhamo Tsering died in New Delhi on 9th January, 1999. He is survived by his wife Tashi Dolma, a son, Tenzing Sonam, three daughters, Dolma, Diki Yangzom, Tenzing Chounzom; and an adopted daughter, Tsering Yangzom.

Somehow I seem to have left this till the end. Probably I wasn’t sure how it would play, or how the reader might respond to an account of yet another aspect of Lhamo Tsering’s uprightness. But at a time when cynicism is widespread, and corruption has made considerable inroads into our church and society, it may reassure people to know that Lhamo Tsering was honest and conscientious, almost to a fault. Even when he was Minister for Security he would travel to Delhi by public bus, to the frustration of his family who were worried for his safety. In his long career, hundreds of thousands of US dollars of secret funds passed through his hands, without there ever being the suggestion that even a penny of it had been misused. He retired poor. He did not own a house or a car. His wife fleshed out his very inadequate pension with petty trade.

Though Lhamo Tsering was the complete professional and the most meticulous and organised person I have known, there has been the occasional remark on his seeming lack of requisite ruthlessness for the job. And it must be admitted that there was an ambivalence — something of the George Smiley about him. On the other hand, his mildness and concern were among the qualities that elicited the loyalty and dedication of his many agents and fighters. At the height of the Cultural Revolution, when intelligence from China was near non-existent, and — as an old hand informed me — “not a sparrow could move from one village to another without an official permit”, Lhamo Tsering managed to place (and nurture for years) a high-level agent in Lhasa itself.

I was in the Resistance for only a short while and can make no claim to camaraderie or shared experiences with Lhamo Tsering, but I think I speak on behalf of all the common soldiers of Mustang when I say that it was a privilege to have known him, and an honour to have served under him.

Tibetan Review, 1999

* * *

Notes

1. The jail also housed Westerners: druggies, hippies and backpackers who had run afoul of Nepalese law. One such, Jeff Long, wrote of his time in Kathmandu jail with the Mustang group in the Rocky Mountain Magazine, entitled “Going After Wangdu; the Search for a Tibetan Guerrilla Leads to Colorado’s Secret CIA Camp”.

2. With Nepal becoming a democracy in the 1990s the Communist Party became a major force in Nepalese politics and Adhakari even served as Prime Minister for a time. He died on 26 April 1999.

Jamyangla,

So happy to see your writing. I remember reading the eulogy before, but read it again. Great stuff, thank you.

I wonder if these books can be purchased online? If not, where?

TCL

It’s nice to read stories like this and with load of informations of our older generation came through. I really appreciated your writings.

I have read one of the eight book in the past. It imprinted some imaginations in mind still today.

Hope in the future read more rest books.

I certainly hope, all the young Tibetans will read these books. It is part of Tibets untold history. And on my part I can certainly vouch for the deep respect the our brave fighters, including the leaders had for late Lhamo Tsering la. In the camp he was referred to not by name, but fondly, “Drunyik la”. My rookie stint was a little after Jamyang la, with strongmen like, Lhasang Tsering la and Tashi Tsering La. During my time there, I did not have any idea who he was but he was mentioned a lot. And at HQ there was an area which the fighter said was specially designed for the soldiers to exercise by Drunyik la. It had some sort of a parallel bar and some other home made equipment. But most important of all or rather most unfortunate of all, was the first time I saw him in the flesh, but alas a witness to his arrest in Pokhara in the summer of 1974 and the subsequent fall of Mustang. I also got to read a letter sent by the late Gyado Wangdu to the Nepalese Government, requesting them to release Lhamo Tsering la, as he was not involved in the guerrilla force but was a Tibetan welfare officer. The letter was sent to Thargay Gompa leader(my apologise I forget his name) but since the letter was written in English, he asked for me. This was at the Annapurna Hotel in Pokhara, where I was temporarily stationed before I was to returned to Mustang. Later in the evening when all the leaders at the Hotel found out what had happened everyone became very despondent. Well this is another story for another day perhaps.

Jamyang Norbu la, you being a regular commentator on tibetan politics with high credibility that people cast upon your works always, we expect you to come up, soon, with a piece on this on-going LS’s PT sacking case, throwing lights on its complexities! Interference and involvement from people like you is much called for at this time when the society is confronting a tough decision. In the past too many of your commentaries on various political issues and events has helped general public guiding and educating politically in the right direction! With regard to this historic on going issue also, people need guidance and advises as ever, and we hope you won’t spare even this too! Thank you!

Beautifully written article. Now it would be appropriate if Jamyang la would shed some light about the sacking of PT by LS. I hear PT has been talking to a lot of people of his termination, because he did not toe the Khashak line. Instead he spoke up for the truth.

The man has no job offer even in Dhasa, just goes to show the height of vendetta by LS. At the same time, PT was always critical of Jamyang la and his view points. It is ironical that PT has become a victim of the same institution he hallowed. Now only to find himself in the other side of what Jamyang la all along has been against and esposuing for clarity. HH has shown us again by remaining silent.