The condescending Lhasa-centric view of Khampas is that they are brave, warlike, forthright and plain speaking, but (ahem!) not too bright when it comes to politics. Hence Gonpo Tashi Andrugtsang’s creation of the Four Rivers Six Ranges, the paramount resistance force in Tibet, though acknowledged as courageous and patriotic, has often been dismissed as the futile last-act of Khampa defiance. What has nearly always been overlooked is the subtle even sophisticated political thinking that went into the creation of this pan-Tibetan national resistance, which in fact even now defines contemporary Tibetan political identity.

I am putting together a longer biographical account of Gompo Tashi, but on this landmark 50th Anniversary of his death, I would like to focus on Gompo Tashi’s political wisdom and vision. I collected information on his life from a variety of sources, but I must thank Loten Drongdetsang of Drayak, Andrugtsang’s chief secretary for a rewarding in-depth interview. I am also indebted to film-maker Lisa Cathy for the transcript (copy) of a lengthy week-long debriefing interview of Gompo Tashi by the CIA officer Roger McCarthy at Darjeeling in the fall of 1959.

Following the Communist occupation of Tibet and the triumphal march of the PLA into Lhasa, Gonpo Tashi kept a low profile and started collecting information on Chinese personnel and activities, using his own extensive network of traders and muleteers and those of fellow merchants. He also began buying weapons. Gonpo Tashi had already established close relations with officials in the Tibetan government and the religious establishment. He was a close friend of the Finance Secretary Lukhangwa (according to Lukhangwa’s daughter-in-law) and visited his home often for lengthy discussions.

He also became friendly with the Dalai Lama’s Lord Chamberlain Phala. He was also close to Trijang Rinpoche the Dalai Lama’s junior tutor, and many other important lamas and monastic officials. Gompo Tashi was one of the principal sponsors (jindag) of the Three Seats and other major monasteries in and around Lhasa and as such was well known and respected as Andrug Jindag. Among his many crucial connections in Lhasa was General Tashi Pere of the Drapchi regiment, and two of his officers, Major Wangden and Captain Kaldam; and also Captain Tsering Lhagyal of the Police, and few officers from other regiments. Everyone of these Tibetans contributed, wittingly or unwittingly, in one way or the other, to the realization of Gompo Tashi’s vision for a pan national resistance to Communist China’s occupation of Tibet

When the Great Uprising of 1956 broke out in Lithang, Bathang, Chatring, and elsewhere in Kham, Gompo Tashi was approached by a large delegation of young Khampa traders in Lhasa who asked him to approach the Kashag to support the Khampa uprising. Gompo Tashi organized these young men, sending about twenty-four to India to seek arms and training from friendly foreign nations, and kept the others in Lhasa to lobby in the government, monasteries, high society and the mercantile community of Lhasa.

Quite understandably, many Khampa leaders and refugees in Lhasa were outspokenly critical and bitter about the Tibetan government’s lack of support for the uprisings in Kham. But Gonpo Tashi remained silent on the issue. Nowhere in his entire debriefing are any such accusations made. Instead he points out that when fighting broke out in Kham in 1956 “… the government of Tibet made many religious offerings that year and asked the three big monasteries and many others to pray and read religious books for the good of those who had died. The government also asked all incarnate lamas including His Holiness the Dalai Lama to pray for them.”

This is perhaps Gonpo Tashi being diplomatic, but it is also perhaps a reflection of his down-to-earth realism. He clearly saw that the political situation in Lhasa had deteriorated beyond the point where it was possible for the Tibetan government to give any open or meaningful support to the Khampas. With the forced resignations of the strong-willed prime-ministers Lukhangwa and Lobsang Tashi, and the assertive minister Lhalu, the Chinese occupation authorities now pressured the Tibetan cabinet to expel all Khampa merchants and refugees in Lhasa. The Kashag, to its credit, refused to do so.

Gonpo Tashi saw that there was a wellspring of sympathy, and genuine if unsteady support, of a kind, for the Khampas in Lhasa, as demonstrated by the extensive religious services – a considerable expense for the Treasury – that the Tibetan government conducted to benefit of the people of Kham and Amdo. And Gonpo Tashi realized that this empathy, kinship, and common culture could somehow be made to serve his greater purpose, so long as he was patient and did not alienate officialdom, or Central Tibetans in general, with recriminations and angry talk.

Gonpo Tashi had quite consciously been planning to set up a resistance organization, and seems to have established a few networks of agents, but could not do anything more publicly because of the omnipresence of the Chinese security apparatus, and its swarm of spies and informers throughout the city. What he needed was a good plausible cover operation. He got the germ of an idea for one when the Dalai Lama on his return trip from India in 1956 received a “Tenshuk” or a Long Life Prayer Offering at Shigatse.

Gonpo Tashi realized that this Prayer Offering had an underlying political significance that could serve a greater national purpose and he began planning to hold one in Lhasa. In the CIA debriefing he mentions that ideally such an offering should have been made jointly by the people of Amdo, Kham and Central Tibet (Bhod Cholkha Sum) but in the present circumstance would have been conspicuous and provocative, like “a thorn in the eyes of the Chinese”. So he decided to start small, and build up the project as the opportunity arose.

Keeping himself in the background, Gonpo Tashi persuaded an official of the Phara college of Drepung to lead a delegation to the Chamberlain Phala and request that the Dalai Lama accept a Tenshuk Offering from the people of Eastern Tibet. He also instructed the Drepung official that once Phala had agreed, he should ask Phala to request the Dalai Lama to also grant them a Kalachakra initiation and also a teaching of the Lamrim Kati. To everyone’s surprise the Dalai Lama gave his assent. In retrospect it appears that Gompo Tashi might have arranged things with Phala earlier.

When it became known that the Dalai Lama would not only accept a Tenshuk Offering but give a three-day Kalachakra initiation and also a Lamrim (Graduated Path to Enlightenment) teaching, the whole program of events took on universal significance for all Tibetans everywhere, and was discussed endlessly in all the towns, villages, and nomad encampments throughout Tibet. In Lhasa city everyone wanted to participate and contribute to the events. Around this time Gompo Tashi managed to get the Amdowa community in Lhasa headed by Jinpa Gyatso a prominent merchant from Labrang, to join the project. Jinpa Gyatso later became the commander of the Amdo regiment (makhar) in the resistance.

This conferring of the Kalachakra initiation by the Dalai Lama took on this compelling significance for all Tibetans at the time because of the desperate fear and uncertainly everyone felt about the future of their world and even the survival of their families and themselves. The Kalachakra contains prophecies of an apocalyptic war wherein the utopian Buddhist kingdom of Shambala defeats the forces of darkness and ushers in a worldwide Golden Age. Those receiving the Kalachakra initiation were ensured a rebirth in this happy period.

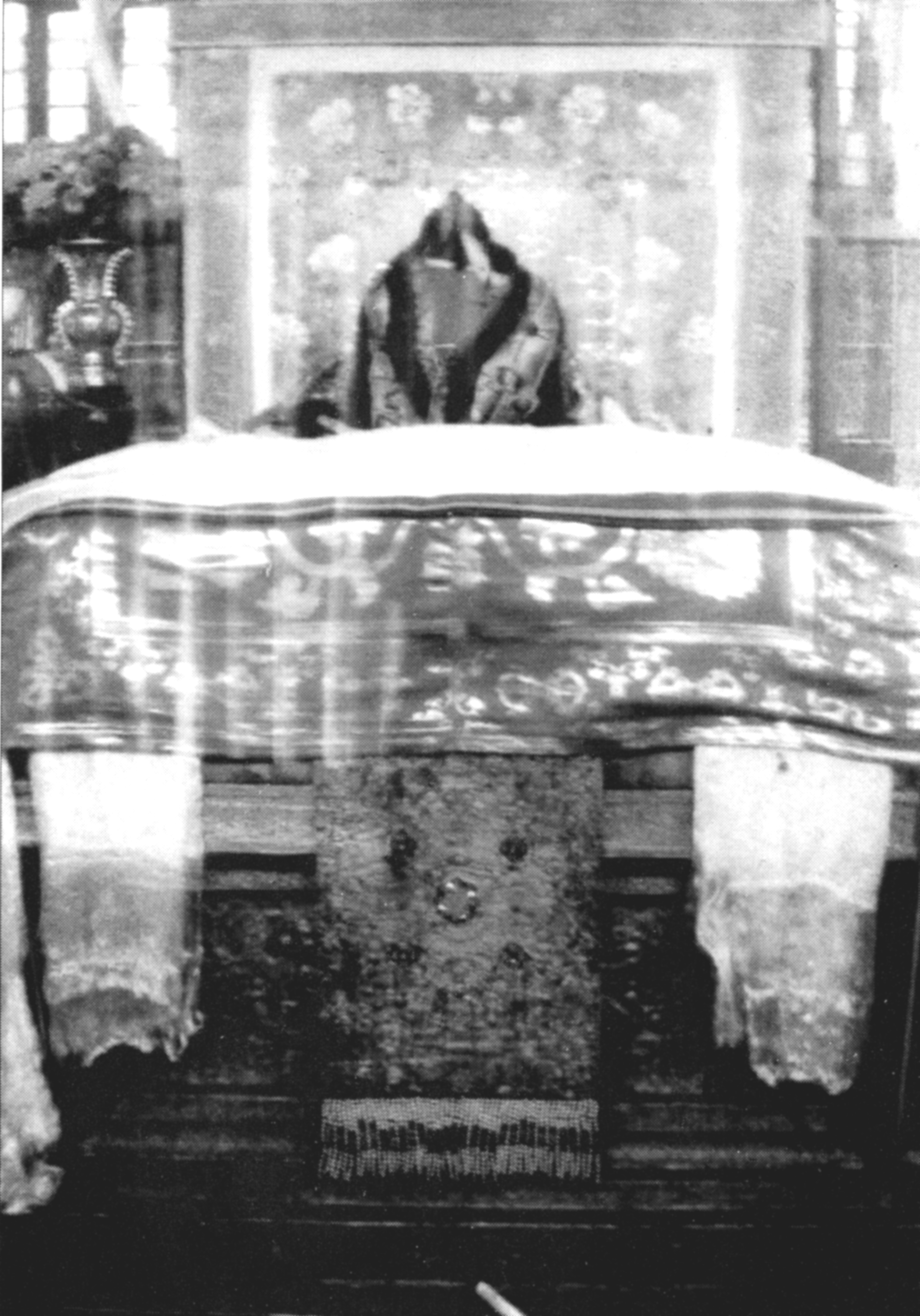

With public support and enthusiasm for the religious events reaching a fever pitch in Lhasa, everyone in the organizing committee (which had swollen considerably) decided that something very special had to be done for the Dalai Lama to thank him for this precious spiritual boon. An idea was floated to offer the Dalai Lama a Golden Throne. It was so tailor-made for Gonpo Tashi’s purpose that one cannot but suspect he had a hand in its inception. Of course the Dalai Lama already had thrones at the Norbulingka and the Potala palaces, but this one would be special. This would not only be the most magnificent and precious throne ever built for a Tibetan sovereign, but would be offered to His Holiness by all his subjects, his people from the three traditional regions of Tibet.

What seemed to have escaped the notice of the Chinese occupation authorities and even the Tibetan government and the Dalai Lama himself, at the time, was that a revolutionary political statement was being made with this offering of the golden throne. Of course the statement was symbolic and wrapped in arcane Buddhist ritual and imagery, but it was supremely nationalistic in that it clearly asserted, not only that Tibet was an independent sovereign state under the sovereign leadership of the Dalai Lama, but that all the people of Tibet were absolutely loyal to him. Furthermore, the statement underscored the fact that this loyalty was not confined to those Tibetans under the jurisdiction of the Lhasa government, but extended to all those Tibetans from all the regions of Kham and Amdo now within the Chinese provinces of Qinghai, Gansu, Sichuan and Yunnan.

In earlier anti-Chinese posters, pamphlets, and political protests slogans in Lhasa the meaning of Tibet had generally been confined to the area under the Lhasa administration. Now the concept of a “Greater Tibet”, of a Tibet that harked back to the period of the old empire was being invoked, and the public was eagerly though largely unconsciously subscribing to the whole enterprise. Gonpo Tashi had raised the political stakes, and the absolutely inspired part of it was that the Chinese seemed completely unaware what was really going on.

As befitted the importance of this venture Gonpo Tashi gives us a detailed list of those involved in the organization of the Golden Throne, and he provides us with their full names and titles, and even their places of origin. Four managers collected contributions from Kham and Amdo, six from Central and Western Tibet, and four from monasteries, incarnate lamas, government officials and aristocrats. Six overseers were appointed to sort and assess the precious jewels collected and four to maintain an inventory of the gold and silver. Five people, including a head chef, were also appointed to take charge of providing tea and meals to the workers. Two water carriers are also mentioned.

Three men were appointed to make the rounds of monasteries and temples throughout Lhasa and neighboring areas to request special prayers, rituals, and readings of sutras to ward off any negative influences that could hinder the project. Another two were appointed to periodically put up prayers flags in auspicious places and make smoke offerings (sangsol) of juniper, sage and incense, to propitiate all gods and deities and obtain their support for the project. Three important people were selected to keep in touch with officials and VIP’s in Lhasa – in case of unforeseen problems.

The organization of the Golden Throne project takes on special importance when we see that many of those taking part in it later became the military commanders and administrative heads in the resistance organization. Gonpo Tashi was creating the structural framework of his resistance army with the organization of this project.

The enormous publicity generated throughout Tibet by the Golden Throne subsequently gave the resistance enough prestige and credibility among the people, to make it possible for it to survive as long as it did. Of course support was not universal, but in my researches I was surprised by the substantial supplies, intelligence, general support and even volunteer fighters the Four River Six Ranges received in Central Tibet, considering that the Chinese were on their best behavior in the region at the time.

The contributions that came in exceeded every one’s expectation. Housewives and aristocratic ladies gave up their ornaments and jeweled headdresses (patruk) and their silver and gold amulet boxes (ghau). Even the city beggars donated unstintingly. In fact so many contributions poured in that Gompo Tashi described his task as “just like drawing water from the ocean”.

Work on the throne started under the supervision of the Serdong Chenmo or the Master Goldsmith, who had a government rank and wore the long turquoise sogchil earing of officialdom. Under him were 49 goldsmith, 19 engravers, five silversmiths, six painters, eight tailors, six carpenters, 3 blacksmiths and 3 specialists to do the soldering and brazing.

Gonpo Tashi provides a detailed inventory of the gold and silver (in the Asian “tola” unit of weight for precious metals) and various jewels that went into the making of the ‘fabulous golden throne” and all its accessories including a golden table, a golden “wheel of the Dharma” and also a number of golden lamps, sets of gold water bowls, and pitchers. Gold and silver lamps, bowls and pitchers were also made for the Jokhang and other important temples and monasteries. In total 55.7 kilograms of gold was expended on this project, not taking into account the silver, gems and precious stones used, and also the money spent on payment and expenses.

This painstakingly detailed account of the precious materials and the organization and effort that went into the creation of the Throne is perhaps Gompo Tashi’s canny way of fixing in the mind of the common man the priceless value of the real treasure of freedom, unity and independence that the Golden Throne symbolized.

On July 4, 1957 (on the 7th day of the 5th Tibetan month of the Fire-Bird year), which Gonpo Tashi notes was a “good astrological day”, the Golden Throne was placed in an open gallery in the Norbulingka palace and the public granted a special audience on that occasion, when the Dalai Lama first sat on the throne. He conducted a special ritual and blessed the gathering. It was also then that he was offered the Tenshuk or “Long Life Ceremony”, which was accompanied by many valuable gifts. Gonpo Tashi reflects on why the people of Tibet were able to construct and offer such a “fabulous and unobtainable” throne to the Dalai Lama, and offers this verse from the sutras:

For those who have crossed the rosary of life,

For those who are fortunate and exalted,

There is no obstacle to the road of success

Even in deeds of great wonder and glory.

I admired Gonpo Tashi and your piece shows he is more than just a patriotic fighter. Thank you Jamyang Norbu la.

Thank you for this article on Gompo Tashi la.This in fact tells the situation of Tibet then too.

Is this Golden Throne still remains in Norbu Lingka Lhasa ?

Your article is a fitting tribute to a great son of Tibet. Isnt HH the Dalai Lama also bestowed the title of Zasar to Gonpo Tashi, the highest honor ever granted to a lay person serving in the military?

Another historical event! Thukje che Jamyang Norbu la.

May be it is just me or few of my friends. When we saw the news of Kalachakra happening in Bodhgaya 2016. My mind at once clicked AGAIN!!!!

Kalachakra now is not a spiritual anymore among TIBETAN DIASPORA. It is a method of people meeting and having a good time gossiping and stuff.

Now the government itself is trying to exploit it, or may be a policy to win people’s heart or reelection.

There have been heroic figures in our long known not so peaceful History

And in recent times this is one.

Andrug Gonpo Tashi under that tumultous period; was able to Unite all the Leaders of Kham (or nearly ALL) & THUS the peoples to form a united VOLUNTEER force to defend all that is TIBET.

That’s a great feat in itself

Thank you for interesting data on Gonpo Tashi Andrugtsang, real hero of the fight for national liberation of Tibet.

Andru Jinda was a great Tibetan warrior and hero and should be remembered for the right reasons but what about the ones that are still alive. The last remnants of a great era gone by. I don’t see anyone talking about them or acknowledging their sacrifice (not that they need it) and I don’t know of anyone in the present govt or any party who have fought and lived through those times.

Today all I see are a few beggars living off the donations and funds given out of pity by other entities or countries. Now the beggars could be misusing either politics or religion for their own gain and it has become like a saas Bahu tv serial never ending and going in circles and the public like the housewife watching these shows and quipping and crying and laughing and bickering and going thru the array of emotions based on the show. In the end it is but a show. As Shakespeare said, life is a stage and we mere actors …

Jinda left us too early but the question is what if he did live thru the ages? Would he have been lost in all the dirty politics that we have seen in the past few decades or would he have shined as a beacon of hope and shown a different path for the generation to come? How should he be remembered ? As a historical figure for the books or as an inspiration and a spiritual guide for the days to come. Who was Jinda and what was and is chushi gang druk? The only guerilla army that fought and died for the country or a political prty without a single known freedom fighter of old facing an identity crisis.

Thank you Jamyang Norbu la.