I wrote this essay shortly after the “Nangpa-la shooting incident” and posted it on Phayul .com, Jan 7, 2007. I haven’t changed anything in the text. My facts and conclusions might be dated somewhat but seem to hold up fairly well, thirteen years later. I’ve added some stunning black & white photographs taken by my friend the Swiss photographer Manuel Baur. His full photo essay can be accessed on https://manuelbauer.ch/pf-beitrag/flucht-aus-tibet/. I also included some clips of the video “Escape From Tibet” and also of the shooting.

In 1994 when I was the editor of the Tibetan language paper MANGTSO, an informant from Solokhumbu sent me a photograph of a Tibetan man, an escapee, who had died somewhere on the Nepalese side of Nangpa-la. His stiff curled-up form reminded me of the 5,000 year-old body of the neolithic man found in an alpine glacier in 1991. Scientists have since speculated that the well-preserved mummy was probably that of a shaman or a priest. The Tibetan body was bigger. It had, of course, not desiccated as completely, but the dark leathery skin on both looked about the same, especially when stretched taut over the skulls — producing those unsettling rictus grins and dark empty eye sockets.

What has always overwhelmed me when hearing accounts of Nangpa-la escapes has not just been the danger of capture or death involved in the crossing, but the incredible physical and mental pain and punishment that the journey seems to involve. We have heard, over the years, of people (largely children and teenagers) becoming snow-blind, frostbitten and losing their toes and fingers. And that appears to be only one installment of a greater ordeal where day after day (about ten days in all) they must endure sub-zero temperatures, constant fear, and unremitting exhaustion and pain. We must bear in mind that although it is a pass, Nangpa-la is nearly nineteen thousand feet above sea level, and at such altitudes every step is a huge and agonizing effort.

A couple of months ago American TV channels carried the account of three experienced American climbers lost on Mt. Hood which is 11,200 ft (lower than Lhasa city) and the massive but unsuccessful rescue attempts made involving trained personnel, helicopters and the latest thermal imaging equipment. The rescuers finally had to give up and it is almost certain that the three climbers are now dead from cold and exposure.

Imagine the anguish and terror the escapees crossing Nangpa-la must have to endure, burdened with the knowledge that far from anyone coming to their rescue if things went wrong, there were actual soldiers, cruel and relentless, stalking them, eager to gun them down like animals. The escapees generally make the crossing in winter or late autumn, when there are less Chinese patrols in the area. Unlike Western climbers or Sherpas, these escapees have no gear to speak of: no climbing boots, no high-performance mountaineering clothes, no sleeping bags, tents, stoves — nothing. Many of the escapees wear cheap Chinese sneakers. Some of them wrap plastic bags around their shoes when going through snow. Practically none of them seem to have down jackets and generally make do with sweaters and coats. One teenage girl probably taking her cue from the latest in Chinese high fashion even appears to be wearing a bright red jacket made of PVC material, which, of course, has all the thermal properties of a sheet of ice.

I remember seeing some of these young Tibetans in Escape from Tibet, the only documentary film that we have about the Nangpa-la crossing, which was released in 1997. It is a moving and instructive film. Unfortunately it is unable to give us a true impression of the horrendous difficulties of the crossing, for the simple reason that the filmmakers were not able to accompany the escapees over the pass. They shot footage of the escapees when they were commencing their journey on the Tibetan side of the border, and later got more footage of them after they had crossed the Nangpa-la and were on the Nepalese side. I am in no way criticizing the filmmakers for this. You would have to be desperate, or at least unaware of the dangers, to try and make such a dangerous journey.

I know of only one inji, a Swiss photographer, Manuel Bauer, who made the crossing, and he told me, quite frankly that he had not realized how dangerous and difficult a trip it was going to be before he started. He accompanied a six-year old girl, Yangdol, whose family wanted to have her educated in India. Her father agreed to take Manuel on the trip if he would sponsor his girl through school since he did not want his daughter to be a burden on the Dalai Lama’s government. The journey started uneventfully enough but once they hit the snow line and began to cross some massive glaciers, Manuel realized he had gotten himself into a situation he had not anticipated. The glaciers were immense and the whole scene frightening in its near cosmic vastness and hostile bleakness.

After a few days in the intense cold Manuel realized he was not drinking enough fluids and his urine was getting darker every time he peed. The problem was that it was so cold that usual expedients like sucking bits of ice or snow were out of the question. Even the water bottle he had under his jacket, against his body, had frozen solid. Manuel had a small primus stove he tried to light. He finally succeeded. There was so little oxygen at that altitude the stove only emitted a weak, barely visible flame that had practically no warmth at all.

Then things became really desperate when the father got frostbite and began to break down mentally. Manuel was now peeing blood. He thought it was the end. What surprised him, and kept him and the father going, was the little girl. Throughout the trip she had not once complained, cried or asked to be carried. Even now she continued walking slowly ahead of the two exhausted men. Somehow they made it across the pass and into lower altitude on the Nepalese side. They rested by a small icy stream. It was slightly warmer here, Manuel noticed the little girl picking the few tiny wild flowers that somehow managed to grow there in between the rock outcrops. She came over to him and shyly offered him a small bouquet. That’s when he broke down and cried.

When you think of these tough desperate Tibetan children like Yangdol, and so many others, undergoing such horrendous trials to find some kind of life of freedom, whether in a school or a monastery in India, or even a chance to get to Canada or the States, then the shootings last year on the 30th of September, of the two young Tibetans, a nun, Kalsang Namtso (17) and a young man Kunsang Namgyal (20) at Nangpa-la, and the arrest of thirty-two others (including 14 children) fills you with black depression and overwhelming anger against China and the Chinese people. The killings were so absolutely unnecessary. So many of these young people die of cold, exhaustion and exposure on the glaciers anyway. Was it necessary for the Chinese to deliberately gun them down “like dogs” as one observer put it?

World Reaction to Nangpa-la Shooting

It is important to place the context of the shooting in its correct perspective. Of course only two people were killed this time around (though we can be certain that, unbeknown to us, more have been killed before) and there are, unquestionably, greater massacres taking place around the world. It is the deliberate casualness of the act that sets it apart. In fact it could be argued that the shooting deaths of these two young people was far more cold-blooded and criminal than many other cases of killings of civilians around the world. First of all the Nangpa-la shootings did not happen in a conflict zone. Tibetans are not launching Qasam rockets against China. Tibetans are not sending suicide bombers to Chinese cities. Tibetan leaders are not calling for Communist China “to be wiped off the face of the earth”. They are in fact doing everything they can to accommodate Beijing’s demands.

The Tiananmen massacre has been rationalized by some Western experts with the observation that the regime’s power was being threatened by the students. But what threat did those young Nangpa-la escapees constitute to China’s control of Tibet? The killing of the two Tibetans could not even be compared to the shooting of innocent civilians by policemen, that sometimes happens in New York or LA when policemen panic, overreact or make a bad judgment call. In Nangpa-la there was no threat (real or even perceived) no panic and no mistake.

The shootings took place in bright sunlight and the victims were many hundreds of yards away with their backs to the Chinese soldiers and moving away slowly; clearly no threat at all. But the Chinese did not even bother to shout at the Tibetans to stop, or even fire a warning shot. A Czech climbing expedition leader, Josef Simunek, who witnessed the shooting, stated: “We felt as though it was 20 years ago in our country in the Communist time, when Czech soldiers killed Czech citizens in their escape over the ‘Iron Curtain’.” While on the subject of the “iron curtain” it must be said that as standard procedure the VoPo (the East German police) always fired a warning shot before they actually opened fire on anyone attempting to escape across the wall.

The Chinese callously gunned down these two Tibetans because they knew they could get away with it. They knew there would be no outcry in the world, and the little there was would be played down or explained away by the increasing number of media people, academics, businessmen and politicians in the West who do China’s bidding. Even though the shootings were most fortuitously caught on video and appeared as brief news-reports on TV networks worldwide, there were practically no editorials, op-eds or commentaries from any major newspaper or TV networks condemning the shooting. Even the usually reliable BBC just came out with a barebones report. The New York Times carried nothing –– but cynically featured a full color, front page, tourist attraction piece on Tibet in its “Sunday Travel Section” a week later. The European Parliament and a couple of other heads of legislative bodies raised some formal objections. Tibetans around the world demonstrated, held vigils and prayers but nowhere on the scale and fervor as before.

Exile Leadership Reaction

Dharamshala remained silent for well over two weeks. An odd third-person statement was issued only on the 17th of October, which stated that Kalon Tempa Tsering strongly condemned the shooting, but which was prefaced by the declaration that the statement was being issued by the exile government “even as it remains committed to the ongoing process of the Sino-Tibetan dialogue.” A letter from the Tibetan Parliament-in-exile to the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights stated that the parliament “was greatly saddened by this uncalled for incident”. The phraseology of these announcements: “incident, “strongly condemn” and “greatly saddened” appear more suited to a statement coming from a third party, like the UN or the European Union, rather than from the bereaved and outraged leaders and representatives of the people who were murdered.

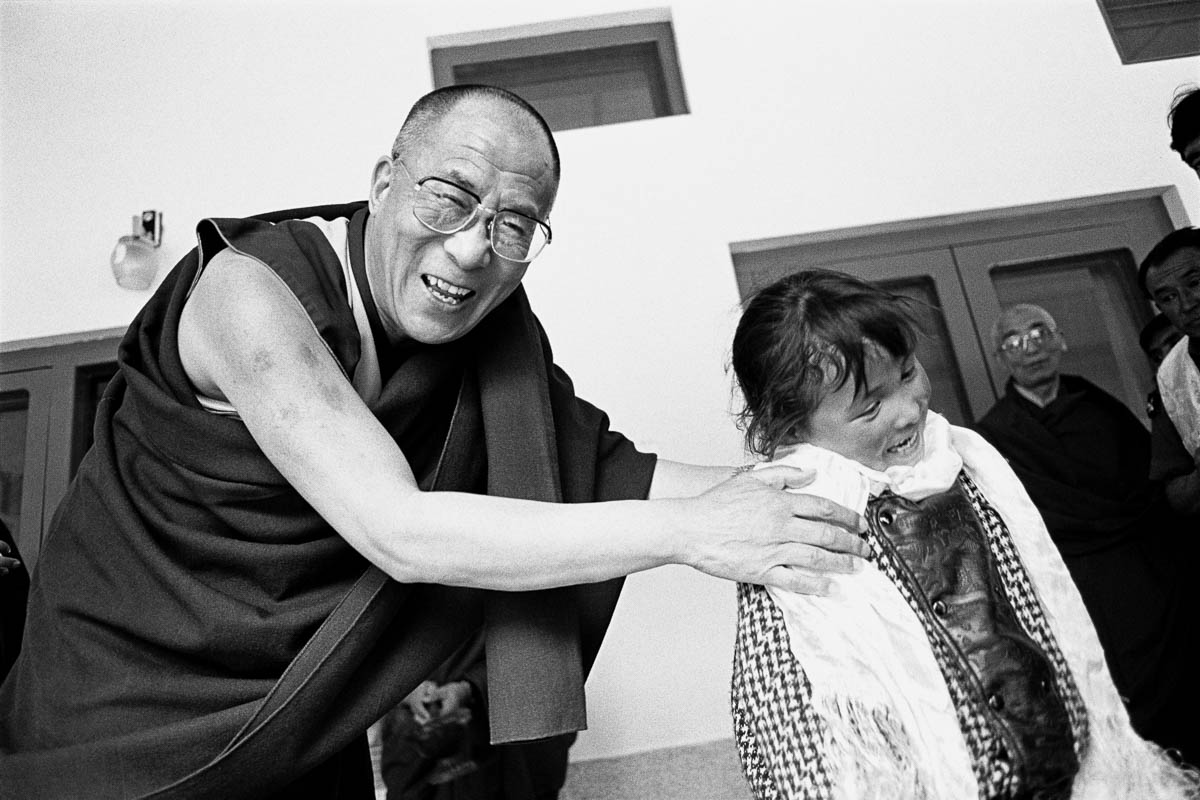

His Holiness did not make any specific statement about the shooting. Following the days after the shooting, he made a statement calling for the control of the global arms trade. Some days later he warned against “a clash of civilizations” and prior to his visit to the Vatican he appealed to the world not to stigmatize Muslims. In Rome, His Holiness in an interview was asked about the Nangpala shooting and he told AP Television News on Saturday (14th) that it was “… very sad. We have been experiencing such cases for more than fifty years. Very sad,”. Perhaps his Holiness meant to convey something stronger or he did actually speak at length on the topic and AP TV News edited it out. I don’t know. But the outcome was that his brief response appeared to play down the tragedy. It is “sad” when your parents die of old age. When defenseless children are murdered in cold blood by Chinese soldiers, something far more forceful, full-throated and condemnatory is required by way of expression and action.

Members of the exile government and parliament were probably upset about the shootings as any one of us. Furthermore, there can be no doubt that His Holiness must have been, more than anyone else, extremely distressed by the incident. After all, he has been meeting nearly every one of these escapees, over the years, and hearing their stories directly from them. It is obvious that he was being held back from expressing his grief and anger by an extremely powerful constraint: to not offend the Chinese leaders in any way that might adversely affect the long hoped-for, much-hyped (but never actually taking place) negotiations with Beijing.

Since the eighties I have written about the irrationality of Dharamshala’s Middle Way policy and the futility of hoping for any kind of meaningful negotiations with China — and I do not think I could bring myself to write anything more on the subject. If the reader wants up-to-date and insightful analysis of the subject I can only refer them to three excellent articles: Tenzin Sonam’s “Tibet At A Crossroads? – A Personal View” in Phayul.com, Sept. 18, 2006, Ketsun Lobsang Dondup’s “Independence as Tibet’s Only Option: Why the Middle Path is a Dead End”, in Tibetan Review Sept. 2006, and Elliot Sperling’s “Incarnation: the Tibet Movement Reaches the End of the Line.”

What I want to do in this retrospective is share with the reader my growing fear that Beijing, by dangling the promise of negotiations before the government-in-exile, has somehow put itself in a position of controlling the thinking and actions of the Tibetan leadership, even manipulating and muting Dharamshala’s reaction to such a monstrous outrage as the Nangpa-la shootings. Think back to the time in 2002 as well as in 2006, when Prime Minister Samdong Rimpoche appealed to the exile public not to protest the US visits of the Chinese President Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao to America. When some Tibetans and supporters ignored Rimpoche’s call and carried out small demonstrations, Chinese embassy officials at the scene, in both instances, reprimanded the demonstrators, shouting at them “didn’t your leaders tell you not to demonstrate?” Then we have the Dalai Lama’s statement of support for China’s hosting of the 2008 Olympic Games, which the Olympic Committee and China supporters effectively used to discredit the worldwide campaign that Tibetans and International Support Groups had launched to deny China the Games.

Many of the statements coming from Dharamshala in the last few years give the strong impression that they have been drafted, or at least instigated, by the Chinese propaganda ministry. For instance, we have Samdong Rimpoche talking about the benefits of the Chinese railroad to the Tibetan people and their economic welbeing. Quite recently we have had His Holiness telling Indian journalists that it was in the interests of Tibetans for their country to be part of China, since China was a global economic superpower. He has, on occasions, also compared Tibet’s position in China to that of a member state in the European Union. I know His Holiness is well aware that unlike Tibet in China, EU member states joined the Union voluntarily, and were not invaded militarily like Tibet, or face the threat of invasion like Taiwan. Furthermore no citizen of the EU has been shot for trying to escape from Europe. So the question remains why His Holiness says these things he knows are patently not true.

“Spritual Leader of China” ?

Aside from the hope of political negotiations with Beijing, there appears to be another powerful inducement for His Holiness and Tibetan leaders to propitiate Beijing. The inducement in this instance is not being proffered directly by Beijing but seems to be coming somewhat circuitously, in discreet increments, from subsidiaries working from within New Age and Dharma circles connected to the Dalai Lama. Over the last decade, a delusion has been cultivated within Tibetan leadership that Tibetan Buddhism could become the dominant, perhaps even the state religion of China. An unspoken corollary to this eventuality is that the Dalai Lama could somehow be accorded the larger role of spiritual leader of the Chinese people. Some years ago, Samdong Rimpoche in an interview in The New York Times said: “Political separation from China is not important … China is not our enemy. China is a people (sic) who need our cooperation, who need our guidance, spiritually. It has been so for more than 1,000 years.” His Holiness in an interview in the South China Morning Post said that “Tibetan culture and Buddhism are part of Chinese culture. Many young Chinese like Tibetan culture as a tradition of China.”

The Dalai Lama’s special emissary, Lodi Gyari (who is a former tulku) made this bizarre claim in a two-part interview in Rediff.com : “One of the most decisive factors in the Tibetan issue is this newly found interest for Buddhism in China. Thirty years ago, for the Chinese, Tibet was the most backward piece of land of the planet and Tibetans were the most retarded people.” Gyari now believes that Chinese attitudes have changed: “Today in places like Lhasa, you see young and erudite Chinese walking shoulder to shoulder with Tibetan nomads. For them, it is very auspicious; they are on pilgrimage.” In the same interview, Gyari claimed that there was a tremendous “extent of reverence” for the Dalai Lama throughout China, even among officials in the Chinese government and the Communist Party. Gyari felt that this reverence even extended to Chinese entrepreneurs and business community who believed “… that what China really needs is the presence of His Holiness.”

This is a dangerous delusion, bordering on megalomania, for His Holiness to consider, even fleetingly, or for his advisors to encourage, even in the most marginal way. The Qing Emperors were not only Buddhists but Tibetan Buddhists and were regarded by many Tibetans as the incarnation of Manjusri. When His Holiness the Thirteenth Dalai Lama, the emperor’s spiritual mentor, came to Beijing in 1906 he was humiliated by the Manchu court, and made to kneel before the Emperor. Following his return to Lhasa His Holiness was hunted down by Manchu troopers like a common criminal. It is fairly certain that had they caught him they would have executed him.

Is it really necessary to point out that the present Chinese government is a rabid Communist dictatorship, ideologically opposed to all religions and unquestionably the most murderous regime the Chinese have had in their history. Is it also necessary to point out the genocide and the catastrophic cultural destruction that took place in Tibet, which we are, even now, unable to fully comprehend or evaluate? For those who insist that economic liberalization has now altered the regime’s attitude to religion, they should cast their minds back to the succession of monks and nuns who have been imprisoned, tortured and sometimes executed in the last many years. Think of the fate of the Panchen Lama (Gendun Chokyi Nima), Chadrel Rimpoche, Tenzin Delek Rimpoche, Khenpo Jigme Phuntsok of Larung Gar besides others. Think also of the reasons why Karmapa Rimpoche, Arjia Rimpoche, and other religious leaders, who the Chinese were cultivating and treating well, escaped from Tibet in recent years.

In May 2006, Zhang Qingli, Communist Party Secretary of TAR, announced his “Fight to the Death” campaign against the Dalai Lama. Tibetans, from the lowliest of government employees to senior officials, have been banned from attending any religious ceremony or from entering a temple or monastery. Patriotic education campaigns in the monasteries have been expanded. Tibetan officials in Lhasa as well as in surrounding rural counties have been required to write criticisms of the Dalai Lama. Senior civil servants must produce 10,000-word essays while those in junior posts need only write 5,000-character condemnations. Even retired officials are not exempt.

Those who insist that this is the handiwork of the Communist Party but that the ordinary Chinese people have “great reverence” for the Dalai Lama, should read the Reuters report of Jan. 13 2007 about a tour group of 125 Chinese Buddhists in Bihar who stormed out of a screening of a documentary on Buddhist sites in the state, because it contained an image or two of the Dalai Lama. “We don’t accept the Dalai Lama as a spiritual leader”, one of the tourists was quoted as shouting. Officials of the Bihar state tourism government were stunned by the reaction.

There is an informal American expression, “reality check,” which means coming to terms with what is actually happening, rather than what one chooses to believe. I would strongly advise Tibetan leaders to conduct such an assessment, and perhaps also look into the various sources from which such enticements and fantasies have been coming from.

In May 2000, I attended the Third Tibet Support Group Meeting in Berlin. During a break in the sessions I was approached by an overseas Chinese, Victor Chan, who claimed he was working for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, and wanted to interview me for a radio show. After a while the discussion took a very strange turn and I realized that this was no interview at all. Chan began heatedly arguing with me about my stand on Tibetan independence and began lecturing me on how there was this amazing renaissance of Buddhism in China and that Tibetan Buddhists could make a tremendous contribution to this movement. He claimed that he felt sure that His Holiness could become the leader of China’s Buddhists, but that in order for that to happen Tibetans had to renounce their demand for independence, since the Chinese “people” would never accept an independent Tibet.

Since then Chan has co-authored a book with the Dalai Lama The Wisdom of Forgiveness. He is also reported to be starting the Dalai Lama Peace and Education Centre with His Holiness’s younger brother, Tenzin Chogyal. Victor Chan appears to be opposed to organizations working for Tibetan freedom and human rights, and in 2004 described Students for a Free Tibet and Canada Tibet Committee activists as “fanatics” to a Canadian newspaper reporter. Chan is most probably just a self-serving ex-hippie, placing himself close to the Dalai Lama to sell his books and promote himself. Yet at the same time it would be imprudent for anyone with even peripheral responsibility for the welfare of Tibet to overlook the possibility that Chan could be an agent of influence (one of many) that the Chinese are using to manipulate His Holiness and the exile government.

The Chinese government has an extensive track-record of employing such well-placed people to effect its own ends. In the United States we have a slew of them, many former secretaries of state, defense, treasury and others, the most well known among them being Henry Kissinger. Nearly all of them have set up consultancy firms that lobby to influence American policy favorably towards China and in return receive access to China’s leaders and government for their corporate clients. I wrote an article in the Tibetan Review in 1989, about how China was employing such Western politicians and certain Tibet “supporters” to influence His Holiness and the exile government to give up Tibetan sovereignty and not get in the way of business with China. My suspicions have become more pronounced over the years.

What Can We Do?

Is there anything we can do right now to counter this sinister influence, this control that Beijing somehow seems to be exercising over our leadership?

There are many different interpretations of why the 10th March Uprisings took place. Of course the official Tibetan one and the Chinese one are profoundly different, but even among professional historians there are significant differences. An unusual and interesting perspective is offered in George Ginsburg and Michael Mathos Communist China and Tibet; The First Dozen Years. They have suggested that Tibetans may have surrounded the Norbulingka not only because of fear that the Dalai Lama was about to be captured, but because of the fear that he would make more concessions to Chinese demands. The Library of Tibetan Works and Archives in Dharamshala has in its oral history project an interview with Barshi Tsendron, a junior official who played a major role in fomenting the Uprising, and his recollections provide considerable corroboration to Ginsburg and Mathos’s conclusion.

In a broad sense, one could say that Tibetans not only believed that the Dalai Lama was in some kind of physical danger, but because of treasonous ministers as Ngabö, his friendship with Chinese leaders and the Marxist ideological education he was given by Phuntsog Wangyal and (earlier in China) by Liu Ke-ping of the Committee of Nationalities Affair, the Chinese were gaining control over his sacred presence, and getting him to make more and more concessions, essentially on matters of national sovereignty. What the Tibetan people basically did on that March day in 1959 was declare: “We want our Dalai Lama back.” And they took him back.

I think it is time, once again, for Tibetans to take the Dalai Lama back. I disagree with the President of the Tibetan Youth Congress who recently suggested that the Dalai Lama should retire. His Holiness is not only the living symbol of a free and independent Tibet but the ultimate resource for the freedom struggle. We all know what everyone in Tibet — from the smallest village in Ngari to the furthest nomad encampment in the Kokonor — wants, is an opportunity to see His Holiness and receive his blessings. This is one of the main reasons Tibetans risk their lives to cross the Nangpa-la. It must be understood that this desire to see His Holiness is not merely a religious aspiration, divorced from people’s sense of themselves as Tibetans. Feelings of identity, uniqueness and nationalism are often expressed in different ways, not necessarily aggressively or politically. The more potent and emotive are often indirect and symbolic. The Dalai Lama may see himself as a “simple Buddhist monk” or a teacher to the world, but for his people he is the living symbol of their long hoped for freedom from Chinese rule. Tibetans must reclaim him to realize this dream.

Tibetans must take him back from his “advisors” and “event coordinators”, and also from his many international appearances: the visit to yet another Benedictine monastery, those well-meaning but completely irrelevant world peace conferences and seminars, and get him back with the Tibetan people –– out on the streets. Try and imagine a march or a demonstration to protest the Nangpa-la shooting in Times Square, New York, led by His Holiness the Dalai Lama. That would make news. That would inspire people. That would electrify. That would shake China.

Some may feel that it would not be dignified for His Holiness to march on the streets shoulder to shoulder with activists and supporters. But there is an absolutely incontestable precedence for this. Gandhi marched, demonstrated, went to jail, and ultimately died for his convictions. But he freed his nation and his people. Many Tibetans worry about what will happen to us after His Holiness leaves us for the “heavenly fields”. They should instead concern themselves with what they can do while he is alive, and do everything they can to aid him in his main task as the leader of the Tibetan freedom struggle. Because in the end that is all that will really matter. That is the legacy by which he will be judged by posterity. All his other achievements will be overshadowed by the success or failure of his fundamental mission to free his nation and people.

The first step that all individual Tibetans must take is to come out and make their conviction and support clearly known to his Holiness — unequivocally, as did all those Tibetans in Lhasa on March 10th, 1959. How do we go about doing that? Well, we could write to him, try and see him personally or start a signature drive. Or we might use the 10th March event itself, to once again, capture His Holiness’s attention and frustrate Chinese machinations.

10th March observances everywhere have, in the last so many years, been noticeably shrinking in attendance and in enthusiasm. Perhaps if we were able to make this year’s demonstrations larger, more exciting and unusually creative and hard-hitting, so much so that it becomes a phenomenon within the Tibetan community and gets people excited and talking, it would effectively demonstrate to His Holiness that his people haven’t given up their struggle, and remind him of the sacrifices they made for him on that same day in 1959. In the past many of us bemoaned the fact that the 10th March rallies had become a tedious annual obligation of refugee existence, something by which we marked our years in exile. It would in a way be a wonderful paradox if we could use this routine event to roll back the apathy and negativity of the past years and perhaps even use it as an initial step to reenergizing the freedom struggle for the critical coming years.

I ask the reader to contact his friends, relatives, community, support groups, political organizations as the TYC, TWA, SFT, Chushigangdruk, and others and persuade and encourage everyone to work on making this years 10th March rallies everywhere, exceptionally dynamic and inspiring.

I am going to be there at the rally in New York City. I have been working on my own placard which reads:

REMEMBER NANGPA-LA! NEVER GIVE UP FREEDOM!